What Second City was for “Saturday Night Live,” a Chicago comedy club was for virtually every black comedian who emerged in the 1990s. All Jokes Aside was a black-owned enterprise that seemed to have infallible taste in talent, perhaps because it was the only club in the country that didn’t relegate blacks to “special nights” or “Chocolate Sundays.” Its opening-night act was Jamie Foxx, then unknown. It introduced or showcased talents such as Bernie Mac, Cedric the Entertainer, Steve Harvey, D.L. Hughley, Carlos Mencia, A.J. Jamal, Sheryl Underwood, George Wallace, Bill Bellamy, Dave Chappelle, Adele Givens, and on and on, including the personnel of the touring Kings of Comedy and Queens of Comedy.

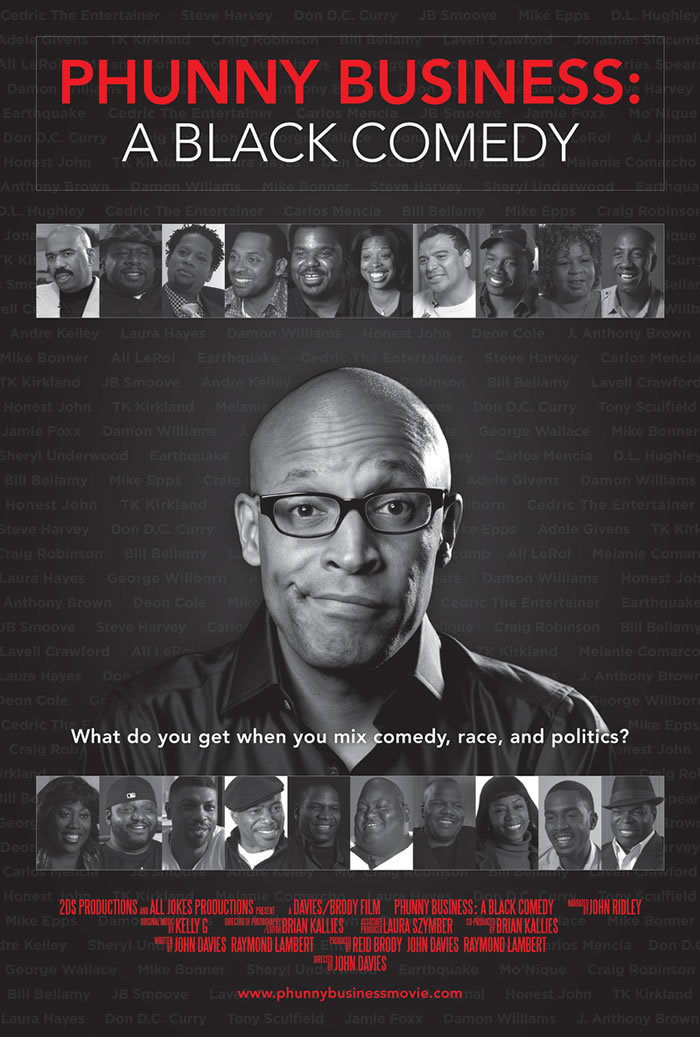

“Phunny Business: A Black Comedy” is a most unexpected documentary about the rise of a club that often sold out three houses a night for 10 years, wasn’t on the radar of many Chicagoans and closed, in a way, as the victim of its own success: When the young comics it launched made it big, they found more money doing concerts on big stages than gigs in a small room.

This is a film not so much about black comedians, although we see and hear a lot of them, but about black entrepreneurs. Raymond C. Lambert, who co-founded the club, began as a stock trader for the firm of the black Chicago millionaire Chris Gardner (who himself inspired the character played by Will Smith in “The Pursuit of Happyness”). After a visit to Bud Friedman’s Improv in Los Angeles, he wondered why a club like that wouldn’t work in Chicago.

Turned out, it would. He opened on Wabash Avenue in the South Loop, booked the best of a new generation, insisted on impeccable manners, dress and training for his staff, made headliners wear suits and ties, and drew affluent crowds. He was also providing almost the only venue in the nation for black female comedians, the threatened subspecies of a threatened species, and booked black gay comics at a time when that was unheard of. He even booked one white comic, Honest John, who backstage one night advised Deon Cole, “try some of this real California weed instead of that Chicago !+,” after which Cole went onstage and found himself suddenly gifted with telescopic tunnel vision.

The film goes in depth about business details, including the peculiarity that All Jokes Aside paid its performer their full fees, promptly, with checks that didn’t bounce, no matter how many tickets had been sold — an achievement few comedy clubs of any description could boast, then and now. One of Lambert’s partners was a woman named Mary Lindsey, herself a trader at the CBOE, who supervised talent with a firm hand, a ready tongue, and dress code inspections.

The film, directed by John Davies, has access to a lot of archival footage, going back to the earliest days when the “stage” was a curtain on a back wall. We get bites from many of the comics, but no extended stretches; the narration and editing often seem to be upstaging the comedians. I would have preferred more comics and fewer montages about Chicago’s weather, women and food. It is also safe to say that we see enough of Raymond Lambert in the film, from the opening titles onward. He’s heard not as a doc-style talking head, but in scripted material that sells itself a little too hard. The comedians come across as more relaxed and natural. Former Sun-Times comedy reporter Ernie Tucker shares warm memories, as do Second City’s John Kapelos and Tim Kazurinsky.

The club on Wabash was the victim of larger paychecks paid by big stages (like the Chicago Theatre, not far away), a rent that doubled, and gentrification as the South Loop underwent a boom. Lambert invested $1 million in a move a mile north to the “entertainment district,” only to face ruinous delays in getting a liquor license (despite a record of 10 years with no incidents). White and Asian owners of nearby galleries and restaurants signed a petition protesting about a change in the “ambience” of the area — meaning, “more blacks.” So it goes.

Still, it was a grand run, and it is good to have it memorialized. Today Lambert says he looks back with satisfaction. He created All Laughs Aside at a time when it was needed, and it achieved what it set out to achieve, and on its stage many of today’s most successful black actors and comedians got their start. Consider that Jamie Foxx, his opening night act, went on to win an Academy Award. And Foxx still gives back: He was the headliner at this year’s benefit for the Gene Siskel Film Center.