On the Rue Bleue in a working-class Jewish neighborhood in Paris, people know each other and each other’s business, and live and let live. That includes the streetwalkers who are a source of fascination to young Momo, who studies them from the window of his flat before preparing supper for his father. Momo’s mother is dead, an older brother has left the scene, and his father is distant and cold with the young teenager. But his life is not lonely; there is Monsieur Ibrahim, who runs the shop across the street. And there is Sylvie, who provides Momo with his sexual initiation after the lad breaks open his piggy bank.

Although Brigitte Bardot (played by Isabelle Adjani) pays a visit to the street one day to shoot a scene in a movie, there was another movie character I almost expected to see wandering past: Antoine Doinel, the hero of “The 400 Blows” and four other films by Francois Truffaut. Not only are both films set within about five years of each other (circa 1958 and 1963), but they share a similar theme: The lonely, smart kid who is left alone by distant parents, and seeks inspiration in the streets.

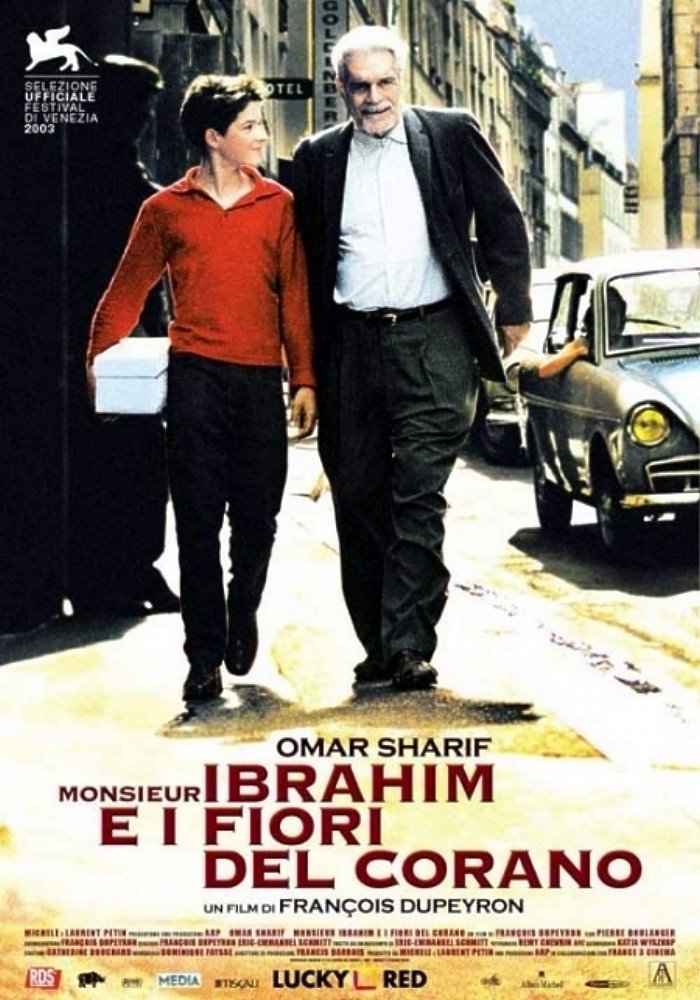

Antoine found it at the movies and in the words of his hero, Balzac. Momo (Pierre Boulanger), whose life is sunnier and his luck better, finds it in Monsieur Ibrahim (Omar Sharif). Although Ibrahim is Turkish, his store is known in Parisian argot as “the Arab’s store,” because only Arabs will keep their stores open at night and on weekends. Ibrahim establishes himself like a wise old sage behind his counter, knows everyone who comes in, and everything they do, so of course he knows that Momo is a shoplifter. This he does not mind so much: “Better you should steal here, than somewhere you could get into real trouble.”

The old man sees that the young one needs a friend and guidance, and he provides both, often quoting from his beloved Koran. He knows things about Momo’s family that Momo does not know, and is discreet about Momo’s friendship with the hookers. What Ibrahim dreams about is to return someday to the villages and mountains of his native land, to the bazaars and dervishes and the familiar smells of the food he grew up with. What Momo desires is a break from a home life that is barren and crushes his spirit.

The movie was directed by Francois Dupeyron, based on a book and play by Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt. Its best scenes come as the characters are established and get to know one another. Sharif at 71 still has the fire in his eyes that we remember from “Lawrence of Arabia,” and is still a handsome presence, but he settles comfortably into Monsieur Ibrahim’s shabby life and doesn’t bore us with his philosophy. And young Boulanger, like Jean-Pierre Leaud all those years ago, has a quick, open face that lets us read his heart.

The last third of the film is more like a fantasy. Momo and Ibrahim both want to escape, Ibrahim buys a fancy red sports car (like the one Bardot was driving), and they drive off to Turkey. What happens there, you will have to discover on your own, but while “The 400 Blows” ended on a note of bleak realism, “Monsieur Ibrahim” settles for melodrama and sentiment. Well, why not? Momo is not as star-crossed as Antoine Doinel and Ibrahim achieves a destiny he accepts.

But isn’t it sort of sad that a movie has to be set 40 years ago for us to accept an elderly storekeeper buying a sports car and driving away with a teenager, without ever for an instant suspecting the purity of his motives? The innocence that Antoine and Momo lose in their stories is nothing compared to the world that teenagers live in today.