The key to the whole thing is Dudley Moore‘s absolutely and unquestioned sincerity. He loves both women. He would do anything to avoid hurting either woman. He wants to do the right thing but, more than that, he wants to do the kind thing. And that is how he ends up in a maternity ward with two wives who are both presenting him with baby children. If it were not for those good qualities in Moore’s character, qualities this movie goes to great lengths to establish, “Micki + Maude” would run the risk of turning into tasteless and even cruel slapstick. After all, these are serious matters we’re talking about. But the triumph of the movie is that it identifies so closely with Moore’s desperation and his essentially sincere motivation that we understand the lengths to which he is driven. That makes the movie’s inevitable climax even funnier.

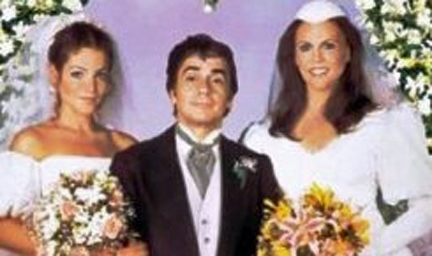

As the movie opens, Moore is happily married to an assistant district attorney (Ann Reinking) who has no desire to have children. Children are, however, the only thing in life that Moore himself desires; apart from that one void, his life is full and happy. He works as a reporter for one of those TV magazine shows where weird people talk earnestly about their constitutional rights to be weird: For example, nudists defend their right to bear arms. Then he meets a special person, a cello player (Amy Irving) who has stepped in at the last moment to play a big concert. She thinks he has beautiful eyes, he smiles, it’s love, and within a few weeks Moore and Irving are talking about how they’d like to have kids. Then Irving gets pregnant. Moore decides to do the only right thing, and divorce the wife he loves to marry the pregnant girlfriend that he also loves. But then his wife announces that she’s pregnant, and Moore turns, in this crisis of conscience, to his best friend, a TV producer wonderfully played by Richard Mulligan. There is obviously only one thing he can do: become a bigamist.

“Micki + Maude” was directed by Blake Edwards, who also directed Moore in “10,” and who knows how to build a slapstick climax by one subtle development after another. There is, for example, the fact that Irving’s father happens to be a professional wrestler, with a lot of friends who are even taller and meaner than he is. There is the problem that Moore’s original in-laws happen to pass the church where he is having his second wedding. Edwards has a way of applying absolute logic to insane situations, so we learn, for example, that after Moore tells one wife he works days and the other one he works nights, his schedule works out in such a way that he begins to get too much sleep.

Dudley Moore is developing into one of the great movie comedians of his generation. “Micki + Maude” goes on the list with “10” and “Arthur” (1981) as screwball classics. Moore has another side as an actor, a sweeter, more serious side, that shows up in good movies like “Romantic Comedy” and bad ones like “Six Weeks,” but it’s when he’s in a screwball comedy, doing his specialty of absolutely sincere desperation, that he reaches genius. For example: The last twenty minutes of “Micki + Maude,” as the two pregnant women move inexorably forward on their collision course, represents a kind of filmmaking that is as hard to do as anything you’ll ever see on a screen. The timing has to be flawless. So does the logic: One loose end, and the inevitability of a slapstick situation is undermined. Edwards and Moore are working at the top of their forms here, and the result is a pure, classic slapstick that makes “Micki + Maude” a real treasure.