“Mean Creek” opens with a schoolyard bully picking on a smaller kid, develops into a story of revenge, and then deepens into the surprisingly complex story of young teenagers trying to do the right thing. It could have been simple-minded and predictable, but it becomes a rare film about moral choices, about the difficulty of standing up against pressure from your crowd.

Sam (Rory Culkin) is small for his age, bright, articulate. He has become the favorite target of George (Josh Peck), a chubby, spoiled kid whose aggression, we eventually learn, masks a deep loneliness. Certainly George is obnoxious on the surface; I was reminded of specific bullies who operated in the schools of my youth, bullies who never seem to attend our class reunions, although if they did I would cross the room to avoid them. Childhood wounds are not forgiven.

Sam gets pounded by George in a schoolyard fight one day, and that angers his older brother Rocky (Trevor Morgan). Rocky is a teenager whose triumphs are behind him: He got points for smoking and drinking before anyone else did, was probably sexually active at an early age, was macho and good-looking, was popular within a narrow range, and is now facing his working years without the skills or education to prevail. He’s a type familiar from Richard Linklater’s “Dazed and Confused,” the recent high school graduate still hanging out with younger kids because those his own age have moved on.

Sam runs with a crowd of close friends, including Marty (Scott Mechlowicz), Clyde (Ryan Kelley) and Millie (Carly Schroeder), who will become his girlfriend when they figure out their half-formed feelings. Marty has problems, including a father’s suicide and an older brother who picks on him, and of course the bully George knows how to push his buttons.

George is smart and observant, able to hurt with his words as well as his fists, and it’s only in a scene where he’s alone at home that we see how desperately he depends on his video toys and the neat stuff in his room as compensation for a deep loneliness. His problem is his big mouth, his habit of using words to wound even when they put him in danger. His out-of-control rant at a crucial moment is a very bad idea.

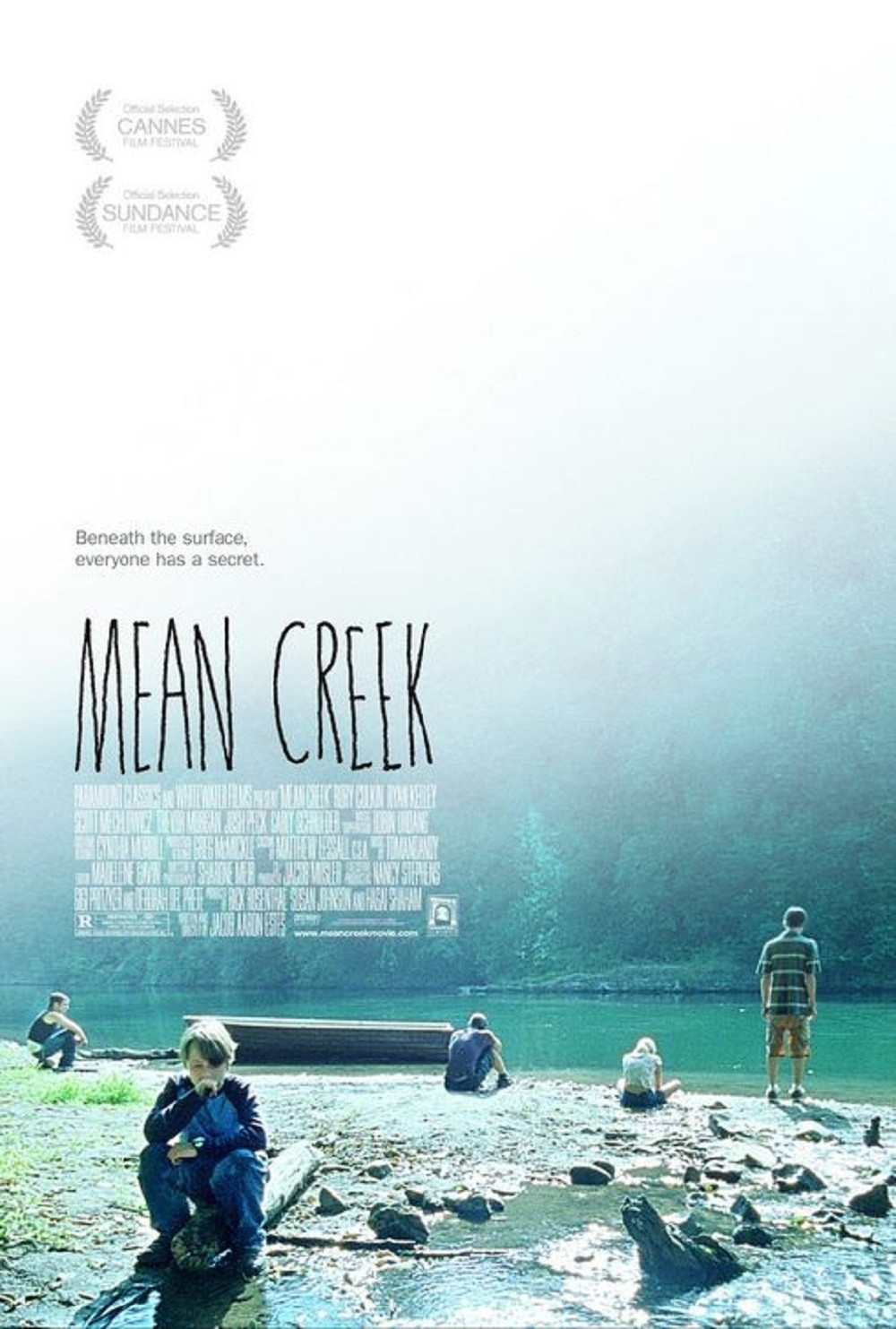

The other kids hang out as a crowd, and, pushed by Rocky and Marty, decide to pull a practical joke on George. “We need to hurt him without really hurting him,” Sam says. They devise a fake birthday party as a way of luring George along on a boat trip, and it is during that trip that their practical joke begins to seem like a bad idea.

Jacob Aaron Estes, who wrote and directed “Mean Creek,” shows in his first film a depth of empathy for his characters, and for the ways the strong-willed ones control the others. It’s extraordinary, the small words and events he uses to demonstrate the discovery of the more sensitive kids — Sam and especially Millie — that George isn’t a monster after all. They begin to feel sorry for him, and talk quietly among themselves about calling off the practical joke. But Rocky and Marty, who personally have nothing against George, want to go ahead; they’re using a crude interpretation of justice to mask their own needs.

The final act of the film is extraordinary. How unusual it is to see kids this age in the movies seriously debating moral rights and wrongs and considering the consequences of their actions. “Mean Creek” makes us realize how many films, not just those about teenagers but particularly the one-dimensional revenge-driven adult dramas, think the defeat of the villain solves everything. Such films have a simplistic playground morality: The bully is bad, we will destroy him, and our problems will be over. They don’t pause to consider the effects of revenge — not on the bully, but on themselves.

“Mean Creek” joins a small group of films including “The River’s Edge” and “Bully,” which deal accurately and painfully with the consequences of peer-driven behavior. Kids who would not possibly act by themselves form groups that cannot stop themselves. This movie would be an invaluable tool for moral education in schools, for discussions of situational ethics and refusing to go along with the crowd.

But the MPAA in its wisdom has recommended it not be seen by those who would find it most useful and challenging; it has the R rating. At Cannes, where the movie was selected for the Director’s Fortnight, Estes ruefully said the rating was “because of a scene where the f-word is used about 1,000 times.” Let it be said that the f-word has been heard and undoubtedly used by everyone the MPAA is shielding from it, and that the dialogue in that scene and throughout “Mean Creek” is accurate in the way it hears these kids talking.