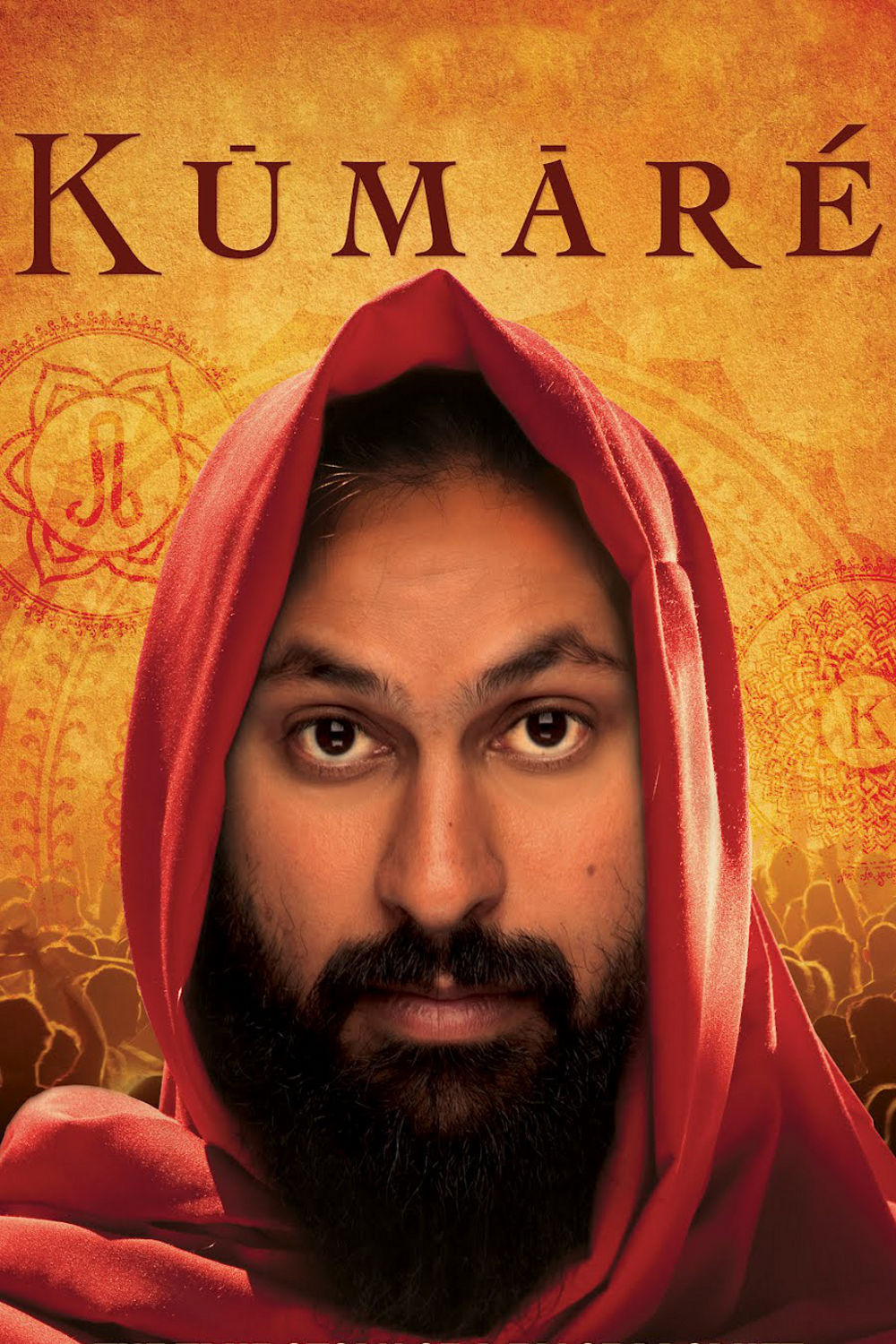

A documentary featuring Vikram Gandhi, Purva Bedi and Kristin Calgaro.

Growing up in New Jersey, Vikram Gandhi was a typical American kid who resented the way his family tried to enforce Hindu beliefs and practices. He found it ironic that Americans began to popularize gurus and yoga just at the time he was growing away from such things. On a trip to India, he says, he found that “real” gurus were no more real than the American frauds who copied them.

That led him into the deliberate deception that he filmed in “Kumare.” He grew a long beard and a pony-tail, exchanged his shoes for sandals, switched his slacks and suits to flowing orange robes, and started carrying an ornate walking stick. Then he moved to Arizona, hired an expert to teach him yoga and a PR woman to promote him as a guru, and began to attract followers in meetings at shopping malls, community centers and around the swimming pools of his affluent clients. His accent was modeled on the way his grandmother spoke English. His teachings were deliberate gibberish: talk of inner blue lights, “finding the guru within,” and chants of fabricated mantras.

At this point in the film, it takes an odd turn. Kumare’s followers believe him without question. They share their deepest secrets with him and visibly appear to benefit from him. These people are not dummies. Mostly middle-aged, they take their health seriously, are somewhat skilled at yoga and follow schedules of meditation. “Kumare” seems to establish that a guru can be a complete fraud and nevertheless do a certain amount of good, because what matters is not the sincerity of the guru but that of his followers.

Gandhi seems typecast for the role of Kumare. Tall, thin, bending forward to listen better, he speaks warmly and encouragingly, and makes deep eye contact. He smiles easily. He never pushes too far. He seems as real as any guru and more real than some. His teaching of yoga seems within the ability of his followers to accomplish. He narrates the documentary (in an ordinary American voice), introduces us to followers he’s grown close to, and begins to believe he may have started something that was out of his control.

He tells his followers the time has come for him to leave them. Now they are on their own. He returns to New Jersey, cuts his hair, shaves his beard, and begins to practice a speech in the mirror: “I am not who you think I am.” Whether he ever says this, and how the movie ends, I will leave for you to discover.

It seems to me that “Kumare” reflects a truth that is often expressed in three words: “Act as if.” If you can act as if something is true, in a sense that makes it true. It doesn’t matter if a teacher’s spiritual teachings have any basis. It doesn’t matter if the supernatural even exists (Gandhi believes it does not). His followers benefit by acting “as if.”

When I first heard this film described, I assumed it would be a satirical, snarky comedy like Sacha Baron Cohen’s “Borat.” Not so. Gandhi seems to be essentially a good man, and he learns things of value to himself in his experiment. In a sense, the deception he practices on his followers is contemptible, but in another sense, they’re all in it together. The film’s implication seems to be: It doesn’t matter if a religion’s teachings are true. What matters is if you think they are.