Early in “Kids,” there is a scene where Telly and his friend Casper are walking along a Manhattan street. Telly, who is about 15 or 16, is describing his latest sexual conquest, which we have just witnessed in heartless detail. Casper is swigging beer from a bottle, which he has probably stolen from a convenience store. Telly’s language is like a series of ugly blows; he talks about his enthusiasm for “de-virginizing” young girls, Casper cheers him on, and it becomes clear that neither one of them has any interests, any curiosity, any values, any frame of reference, beyond immediate animal gratification.

Then a curious thing happens. Casper pauses casually, in plain view of passersby on a street corner, to urinate. That is not what is strange. What is strange is that Telly chooses to stand around the corner from his friend, to lend him privacy. If you study this body language, you realize that these kids live entirely in a world of their own. Other people – adults – simply do not exist.

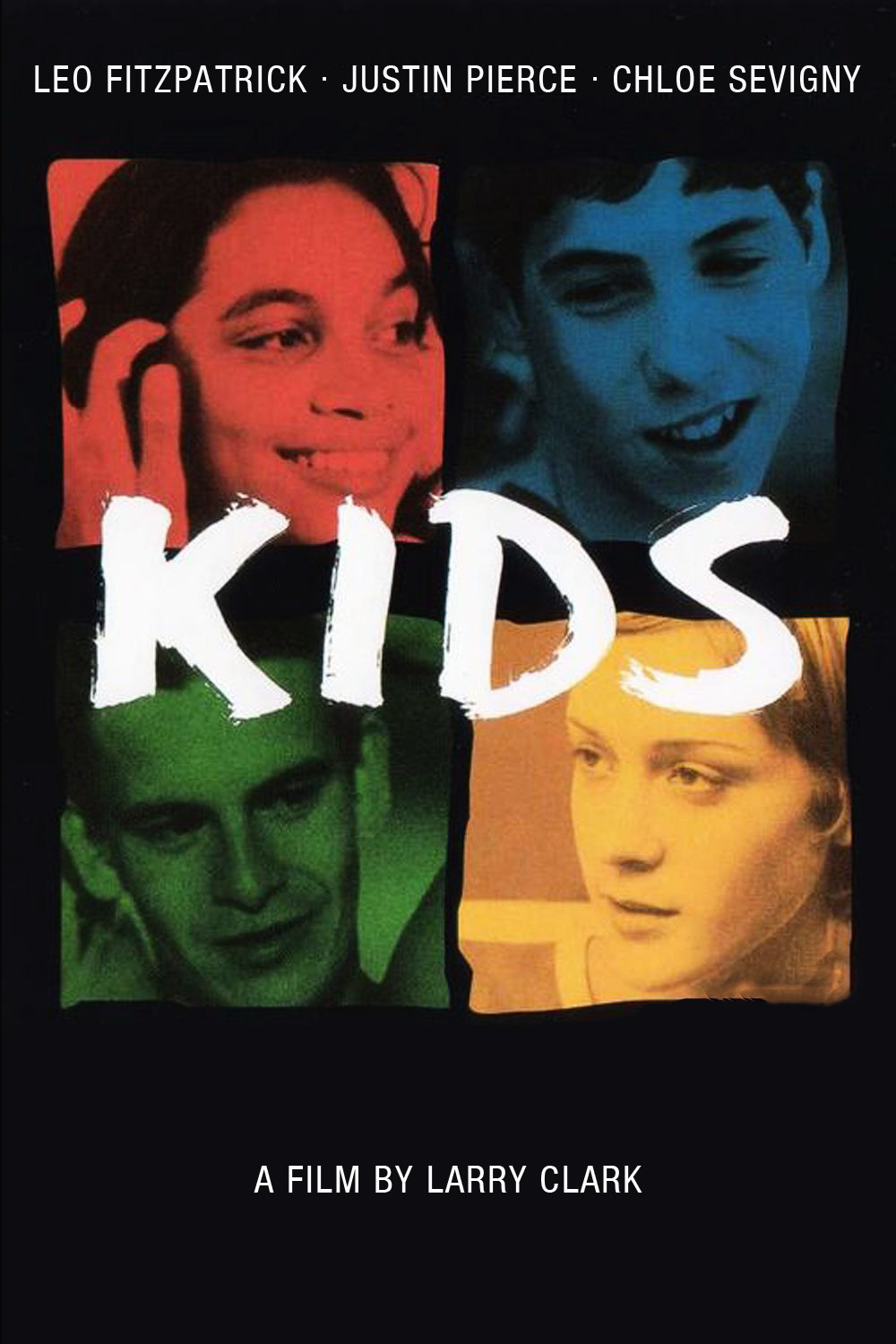

Larry Clark’s “Kids” is a movie about their world. It follows a group of teenage boys and girls through one day and night during which they travel Manhattan on skateboards and subway trains, have sex, drink, use drugs, talk, party, and crash in a familiar stupor, before starting all over again the next day. The movie seesthis culture in such flat, unblinking detail that it feels like a documentary; it knows what it’s talking about.

Telly, played by Leo Fitzpatrick, at least has an interest in life: sex. His face is a scary study in self-absorption as he tells girls lies they should laugh at. Being stupid, naive or simply curious, they listen to him.

“What if I get pregnant,” asks a girl, who looks about 14.

“If you – – – – me, you don’t have to worry about that,” Telly tells her.

“Why not?” “Because I love you. Because I think you’re beautiful.” She believes him. Minutes later, his mission accomplished, he’s back on the street with Casper, explaining his philosophy about virgins: “Say you die tomorrow. Fifty years from now, she’ll still remember you.” It is a good thing he cannot hear the talk among some of the girls in the movie, who cannot even remember losing their virginity.

Clark has published several famous books of gritty photography. In his first movie, he adopts a similar approach, shooting on location in the streets, placing his characters in their world. What is interesting is that you can hardly even see Manhattan in this movie; the camera, like the characters, sees only this sad youth culture. What is not human and between 12 and 17 essentially does not exist.

The casting of Leo Fitzpatrick as Telly has a lot to do with the film’s powerful effect. This is the kind of kid who gives parents nightmares. He is essentially a very effective sex machine, plowing through fields of naive, underage girls. What makes him unforgettable is his voice, which is crude and grating; everything he says sounds unwholesome. Nor is he much to look at. What do the girls see in him? The answer to their curiosity about sex, I guess.

Since Fitzpatrick is an actor (and “no ladies’ man,” he told Clark), this is a performance and, as such, one of the most effective I’ve seen. It’s amazing how, watching the film, you dislike Telly so much you want to deny Fitzpatrick’s accomplishment in creating him.

The movie’s dialogue, which sounds authentic, was written by a 19-year-old named Harmony Korine, who lived in the world of skateboarders and suggested the casting of some of his friends to Clark. There are two extended rap sessions – one for the boys, one for the girls – in which they talk about sex, drugs and their lives.

Gradually, a plot emerges, involving two of the girls, who go for an AIDS test.

The result shadows the rest of the movie, and gives “Kids” its reason for being; the film is intended as a wake-up call, and for some kids, it may be a lifesaver. Other kids should probably not see it. The film received an NC-17 rating by the MPAA, and then a decision was made to release it “unrated”; in many markets, it will be “adults only.” It is so raw, bleak and unfiltered that such a policy is appropriate, and yet there will be kids who should see this movie, and my hunch is, somehow they’ll find it.

Clark’s direction is discreet. He makes his points with character and action, not with speeches. Only five times does his camera stray from the kids. Once is for a scene in a subway, where a blind man sings “Danny Boy” badly while a young man dances to the song, but is out of step. Once is when two Korean storekeepers try to deal with the kids, who are stealing from them. Once is where a wide-eyed little girl is given a peach by Casper, and throws it away.

Once is when Telly briefly visits his apartment, talks to his uncomprehending mother, and steals some money from her. Once is when the kids are on a subway train, and a legless beggar wheels himself through the compartment. Look closely: The platform supporting his half-body is made from a skateboard.

Skateboards provide the way the kids move around town. They gather in Washington Square Park, dope is bought and sold, sexual conquests are related, and they beat up another kid so brutally that he could have been killed. The kid they attack is black, but so are some of the attackers; their pack includes all races. They are color-blind, or perhaps it is more accurate to say they comprise a race of their own.

“Kids” is the kind of movie that needs to be talked about afterward. It doesn’t tell us what it means. Sure, it has a “message,” involving safe sex. But safe sex is not going to civilize these kids, make them into curious, capable citizens. What you realize, thinking about Telly, is that life has given him nothing that interests him, except for sex, drugs and skateboards. His life is a kind of hell, briefly interrupted by orgasms.

Most kids are not like those in “Kids,” and never will be, I hope. But some are, and they represent a failure of home, school, church and society. They could have been raised in a zoo, educated only to the base instincts. You watch this movie, and you realize why everybody needs whatever mixture of art, education, religion, philosophy, politics and poetry that works for them: Because without something to open our windows to the higher possibilities of life, we might all be Tellys, and more amputated than the half-man on his skateboard.