In 1940, some 15,000 officers of the Polish army were rounded up, transported in sealed buses to a forest named Katyn, shot in the back of their heads by the Russian KGB and buried in mass graves. That is the simple truth. When the nation was occupied by both the Nazis and Soviets, their deaths were masked in silence. Then the Nazis dug up the graves and blamed the deaths on the Soviets. After the defeat of Hitler and the Soviet occupation of Poland, history was rewritten and the official version blamed the massacre on the Nazis.

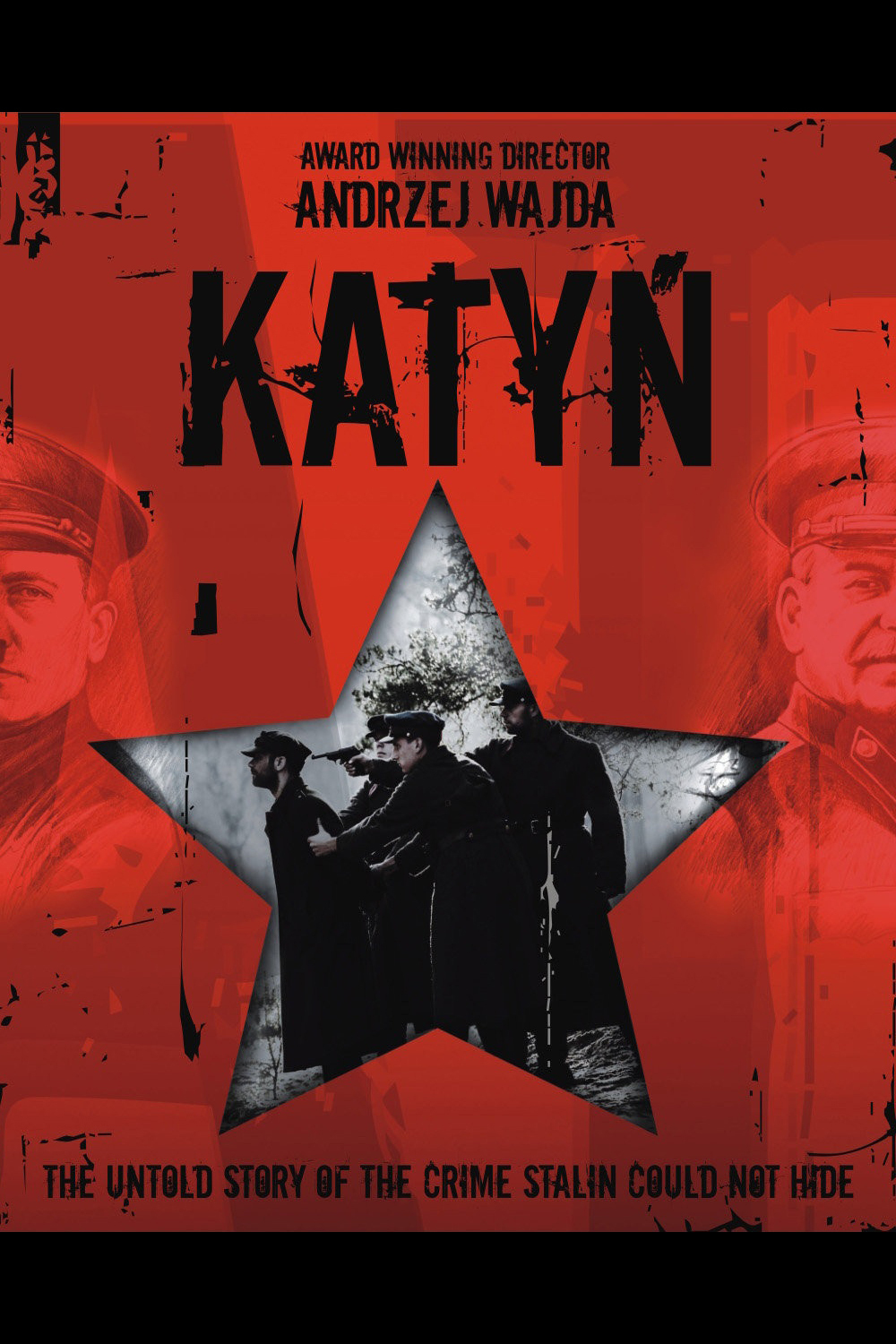

One of the officers murdered that day was Jakub Wajda, whose son Andrzej would become a leading Polish film director, and one of the chroniclers of the Solidarity movement. Now 82, Andrzej has evoked what happened that day and how it infected Polish society for 50 years. Reflect that everyone in Poland knew the truth of the massacre, but to lie about it became an official requirement under the Soviet-controlled regime. Thus, in some cases, to gain immunity or advancement in postwar Poland required parents and children, brothers and sisters of the dead to remain silent about their fates.

This poor bruised nation, trapped by time and geography between the two dark evils of 20th century Europe, has prevailed, and its survival is embodied in the career of Wajda, who in key films starting in the 1950s found a way to say what he needed even under communist national film censorship. His early films, “Kanal” (1957), about the Warsaw Uprising, and “Ashes and Diamonds” (1958), about the Polish Resistance during the war, involved Poland’s two oppressors.

A single image at the beginning of “Katyn” expresses the nation’s dilemma. A bridge is crowded by fleeing civilians — from both ends. Some flee advancing Nazis. Some flee advancing Russians. As the two armies, in concert under the Hitler-Stalin Pact, acted together, such situations took place. The refugees are not tattered stragglers, but ordinary civilians, torn so quickly from domestic security that they carry suitcases, although they could have little idea of the journey ahead for them.

Wajda tells his story through a few characters. We meet Anna (Maja Ostaszewska), traveling in search of her husband Andrzej (Artur Zmijewski), a Polish officer. They are clearly intended as Wajda’s parents; movingly, he has named his father after himself. His father, like many of the Polish officer corps, was not a professional military man, but a reservist, called up from the professional, scientific and educational classes. The 1940 massacre would exterminate many of a generation’s best and brightest.

Lives hang by a thread. Anna succeeds in finding her husband at a deployment camp and begs him to escape with her. He feels his place is with his fellow officers. Neither of them suspect he will be executed. Wajda broadens his canvas to include others, including Andrzej’s own father; his mother, like his wife, waits for word. We meet two other women: the wife of an executed general, who refuse to toe the Soviet line, and the sister of a dead officer, who commissions a plaque in his memory. Her crime is to add the fate of the Katyn massacre, since the Soviets played with time to make correspond to a later period when the Nazis were enemies, not friends.

The actresses playing these roles are all well known in Poland, where I assume they are easy to distinguish. To an outsider like myself, they tended to resemble each other and I was able to follow them by story and plot more easily than facially. This is not really a problem because all are facets of the same experience.

Anna remains the central figure, refusing to accept that her husband is dead until she finally receives the truth from an eyewitness to his remains. So did many loved ones cling to hope, as the POW/MIA relatives do in this country. The dead had no peace. They were dug up by the Nazis to expose Soviet crimes, then dug up again and metaphorically dug up in revisionist history.

The film ends with a scene of relentless horror, showing the assembly line of execution. Men are taken from the sealed buses one by one, their names checked off a list, then quickly walked to their place of death and killed with a bullet to the back of the skull. Their bodies fall or are heaved into mass graves in orderly progress, falling side by side, and buried by bulldozer. Now Wajda has brought some small measure of rest to their names, to Poland, and to history.

Note: “Katyn” was one of this year’s Oscar nominees for best foreign language film.