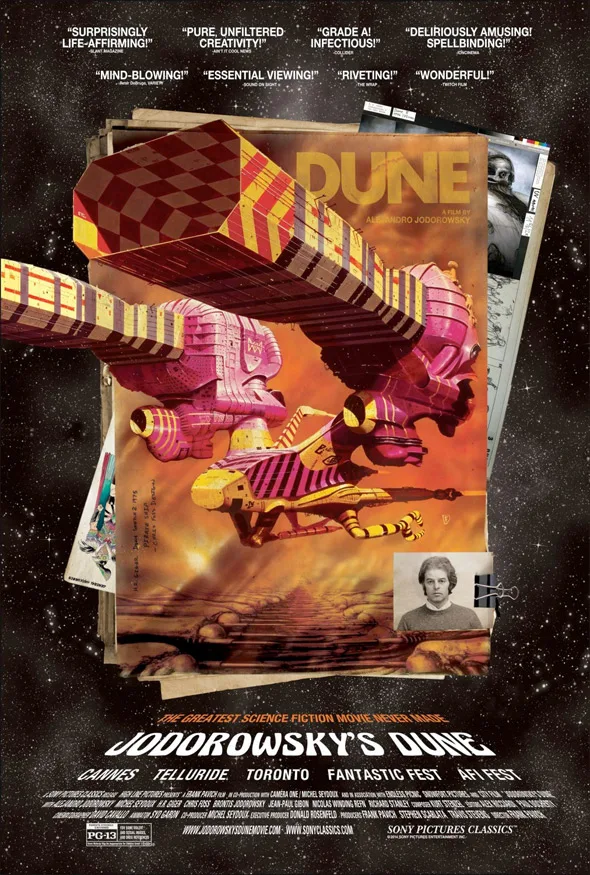

“Jodorowsky’s Dune” is an account of a film that was never made despite all the love that its makers poured into it, yet somehow it’s warm and inspirational: a call to arms for dreamers everywhere.

The possessory credit in the title belongs to Alexander Jodorowsky, director of the psychedelic classics “El Topo” and “The Holy Mountain.” He tried for years to bring Frank Herbert’s novel “Dune” to the screen. We know, of course, that he did not succeed, and that David Lynch’s own version, released in 1984, tanked at the box office, satisfied almost no one, and nearly destroyed Lynch’s career. But as we watch this documentary by Frank Pavich, we never feel that Jodorowsky dodged a bullet, or that he somehow wasted his time. Jodorowsky definitely doesn’t feel that way, although he’s endearingly honest about the relief he felt as he watched Lynch’s version of “Dune” and realized it was “terrible.”

The development process began in 1973, after Jodorowsky released his quasi-experimental religious allegory “The Holy Mountain,” and went on for years. Jodorowsky, now a spry 84-year old, narrates. He’s joined by a preproduction crew that now seems like a 1970s sci-fi All-Star team. The “Dune” gang included the late Dan O'Bannon, who wrote and directed the no-budget favorite “Dark Star” (which inspired Jodorowsky to hire him as special effects supervisor) and went on to write the original “Alien”; “Swiss surrealist H.R. Giger, who made creatures and sculptures for “Alien”; the French graphic artist Jean “Moebius” Girard, of “Heavy Metal” fame; and Chris Foss, who painted cover art for 1970s sci-fi paperbacks.

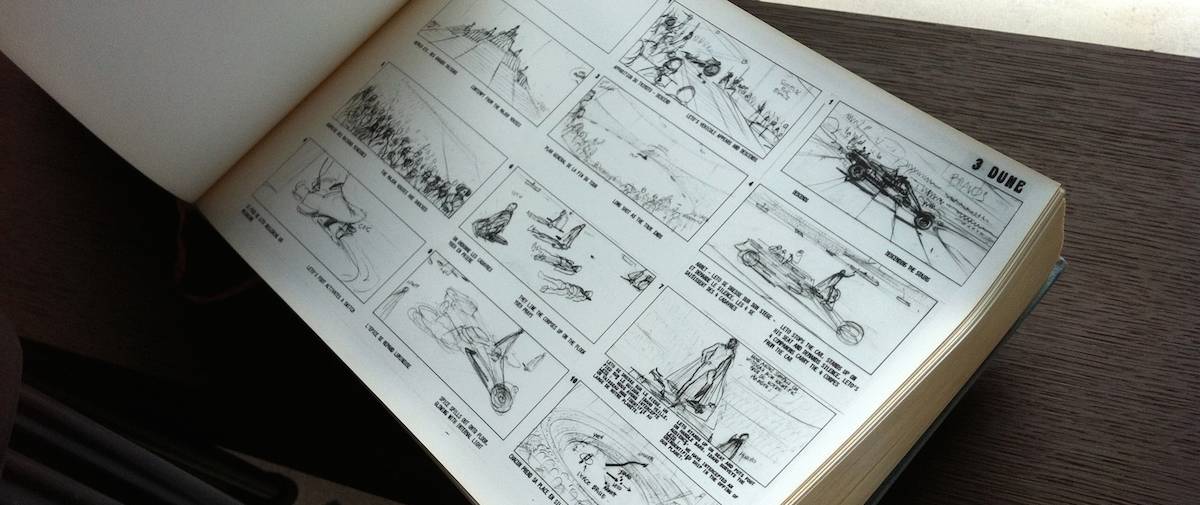

The director captures Jodorowsky’s story in plain-vanilla talking head interviews, dipping down to capture Jodorowsky’s knotty hands as he speaks contemptuously of money, or pausing to watch him dote on a Siamese cat that has wandered onto the set. The film often cuts to storyboards or concept art that has been digitally dismantled and transformed into crude animation. There’s no attempt to “clean up” the argtwork; you can see ink smudges and pencil and erasure lines. Sometimes we get a nice, long look at the art, which has a post-counterculture, Pop Art or underground comix feel; other times the movie cuts away before we’ve had a chance to study them, which can be frustrating. Throughout, Kurt Stenzel’s synthesized score drones and hums. It’s the right kind of score for a mid-’70s Jodorowsky picture: music to trip by.

Jodorowsky’s statements tend toward the grandiose, but you never get the sense that he’s a charlatan, or that he’s overestimating his power to fill the screen with images no one had seen before. Entering the time machine of nostalgia, the director portrays his younger self as a man who thought he could do anything and could make his collaborators feel invincible, too. One would be tempted to write off Jodorowsky’s anecdotes as borderline tall-tales were it not for the hilariously plausible details, such as his convincing Orson Welles to play the morbidly obese villain Baron Harkonnen by promising to have his meals catered by his favorite French chef.

Jodorowsky’s crew validates his robust self-image, describing him as a man who kicked open the doors of their imaginations and nourished them with compliments and useful suggestions. One gets the sense that while copious amounts of intoxicants were surely consumed throughout the process—some of Foss and Giger’s more outlandish illustrations have a whiff of hashish and patchouli oil about them—the most powerful drug was Jodorowsky’s encouragement. “I was searching for the light of genius in every person,” he says, and from the twinkle in his eye you can tell that he means it. His crew worked right up to the edge of exhaustion without resenting him. “He was like a dictator or a cult leader, assembling his army all around him,” says his son Brontis, who was cast as Paul Atriedes, the Messianic hero of “Dune,” and embarked on a six hour a day, seven day a week, two-year regimen of martial arts, swordfighting and gymnastics.

This is, if you take a half-step back, a familiar story. For every movie that makes it to the screen, there are untold numbers that don’t. Just as the lost manuscript looms so large in the writer’s imagination that it becomes the greatest story never published, so too does every unmade film start to seem like a cinema classic snuffed in the womb. Of course every moment of “Jodorowsky’s Dune” has a touch of wistful exaggeration. And of course every projection of what the completed film might have looked like—much less the way it would have supposedly transformed human consciousness!—has to be taken with a grain of spice.

The documentary has tendency to overreach when describing this unmade film’s impact. Yes, some of its effects on future sci-fi movies are undeniable, especially ones that incorporated aspects of the “Dune” gang’s unused concept art. But other chains of influence are impossible to verify, and there are times when you may feel as though Pavich is straining to make the project seem as important to cinema history as it was to Jodorowsky and company. Equally specious is the film’s Lewbowski-like insistence that Jodorowsky’s ideas were so mind-blowing that studio suits just couldn’t handle them, man (more likely that they thought the picture was too long and expensive to be so aggressively weird). And the suggestion that the “Dune” gang lost at movie roulette but won at life seems tonally out-of-whack: an intrusion of Frank Capra-like triumphalism on a story that should take its cues from Jodorowsky’s earthy spirituality. Most of the interviewees make it clear that they think Jodorowsky’s “Dune” was worth doing for its own sweet sake, regardless of its fate in the marketplace.

Although this documentary’s own sense of invention doesn’t rise to the level of its loopy subject, it’s still an engaging work: a testament to the charisma of Jodorowsky and the enduring power of his message, which resonates beyond the confines of sci-fi geekery. “Jodorowsky’s Dune” has something to teach us about success and failure, and the unearned power that we grant those words in our own lives.