Yes, I take notes during the movies. I can’t always read them, but I persist in hoping that I can. During a movie like “House of D,” I jot down words I think might be useful in the review. Peering now at my 3×5 cards, I read sappy, inane, cornball, shameless and, my favorite, doofusoid. I sigh. The film has not even inspired interesting adjectives, except for the one I made up myself. I have been reading Dr. Johnson’s invaluable Dictionary of the English Language, and propose for the next edition: doofusoid, adj., possessing the qualities of a doofus; sappy, inane, cornball, shameless. “The plot is composed of doofusoid elements.”

You know a movie is not working for you when you sit in the dark inventing new words. “House of D” is the kind of movie that particularly makes me cringe, because it has such a shameless desire to please; like Uriah Heep, it bows and scrapes and wipes its sweaty palm on its trouser leg, and also like Uriah Heep, it privately thinks it is superior.

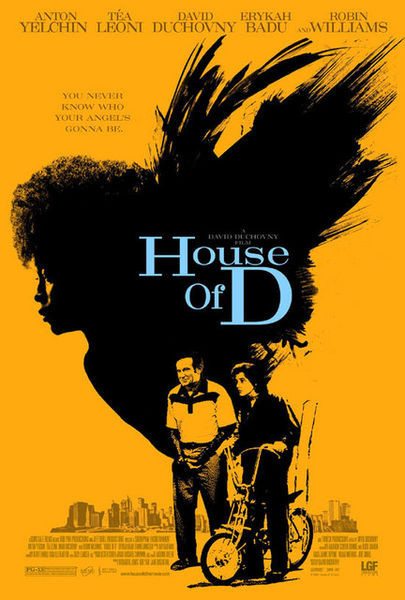

I make free with a reference to Uriah Heep because I assume if you got past Dr. Johnson and did not turn back, Uriah Heep will be like an old friend. You may be asking yourself, however, why I am engaging in word play, and the answer is: I am trying to entertain myself before I must get down to the dreary business of this review. Think of me as switching off my iPod just before going into traffic court. So. “House of D.” Written and directed by David Duchovny, who I am quite sure created it with all of the sincerity at his command, and believed in it so earnestly that it did not occur to him that no one else would believe in it at all. It opens in Paris with an artist (Duchovny) who feels he must return to the Greenwich Village of his youth, there to revisit the scenes and people who were responsible, I guess, for him becoming an artist in Paris, so maybe a thank-you card would have done.

But, no, we return to Greenwich Village in 1973, soon concluding Duchovny would more wisely have returned to the Greenwich Village of 1873, in which the cliches of Victorian fiction, while just as agonizing, would at least not have been dated. We meet the hero’s younger self, Tommy (Anton Yelchin). Tommy lives with his mother, Mrs. Warshaw (Tea Leoni), who sits at the kitchen table smoking and agonizing and smoking and agonizing. (Spoiler warning!) She seems deeply depressed, and although Tommy carefully counts the remaining pills in her medicine cabinet to be sure his mother is still alive, she nevertheless takes an overdose and, so help me, goes into what the doctor tells Tommy is a “persistent vegetative state.” How could Duchovny have guessed when he was writing his movie that such a line, of all lines, would get a laugh?

Tommy’s best friend is Pappass, and played by Robin Williams. Pappass is retarded. He is retarded in 1973, that is; when Tommy returns many years later, Pappass is proud to report that he has been upgraded to “challenged.” In either case he is one of those characters whose shortcomings do not prevent him from being clever like a fox as he (oops!) blurts out the truth, underlines sentiments, says things that are more significant than he realizes, is insightful in the guise of innocence, and always appears exactly when and where the plot requires.

Tommy has another confidant, named Lady (Erykah Badu), who is an inmate in the Women’s House of Detention. She is on an upper floor with a high window in her cell, but by using a mirror she can see Tommy below, and they have many conversations, in which their speaking voices easily carry through the Village traffic noise and can be heard across, oh, 50 yards. Lady Bernadette is a repository of ancient female wisdom, and advises Tommy on his career path and the feelings of Pappass, who “can’t go where you’re going” — no, not even though he steals Tommy’s bicycle.

Then whole business of the bicycle being stolen and returned, and Pappass and Tommy trading responsibility for the theft, and the cross-examination by the headmaster of Tommy’s private school (Frank Langella) is tendentious beyond all reason. (Tendentious, adj. Tending toward the dentious, as in having one’s teeth drilled.) The bicycle is actually an innocent bystander, merely serving the purpose of creating an artificial crisis which can cause a misunderstanding, so that the crisis can be resolved and the misunderstanding healed. What a relief it is that Pappass and Tommy can hug at the end of the movie.

Damn! I didn’t even get to the part about Tommy’s girlfriend, and my case is being called.