Pedro Costa’s first narrative film in nine years, “Horse Money,” is as gorgeous and impenetrable as a dream. It might be set in an afterlife where souls contemplate their lives (and their mistakes, and their misfortunes), or there might be something else to it; like many of the Portuguese filmmaker’s works, this one teases and baffles but refuses to explain itself. It makes a quartet of what was once called the Fontainhas Trilogy. It is named after the poor neighborhood in Lisbon where Costa originally went with 35mm film equipment to make a lush dramatic feature in the 1990s, only to abandon it and shoot the film with a small video camera—a decision that led Costa down the path that eventually developed his unique aesthetic, which is simultaneously gritty and glossy, a look that delves into the emotional essence of experience by bypassing the signifiers of “realism” entirely.

The film’s main character is the 60-year old Ventura, a working class Cape Verdean immigrant. He’s playing a highly stylized version of himself in situations drawn from his own life, developed in conversations with his friend Costa. Ventura was the star of Costa’s last film, “Colossal Youth,” and although Costa has suggested that Ventura, never a professional actor anyway, probably doesn’t have any more movies left in him, one hopes that they will continue to work together, because theirs is one of the great actor-director collaborations in recent cinema.

The intervening years since their last film together have not been kind to Ventura. He (or the character? is there a difference?) has a nerve disease that makes his hands shake. Where he seemed mysterious and implacable, rock-like at times, in much of “Colossal Youth,” here he seems mostly regretful and anxious and often terrified. His lack of vanity as he confronts his own physical decline verges on heroic. There is no vanity in this performance.

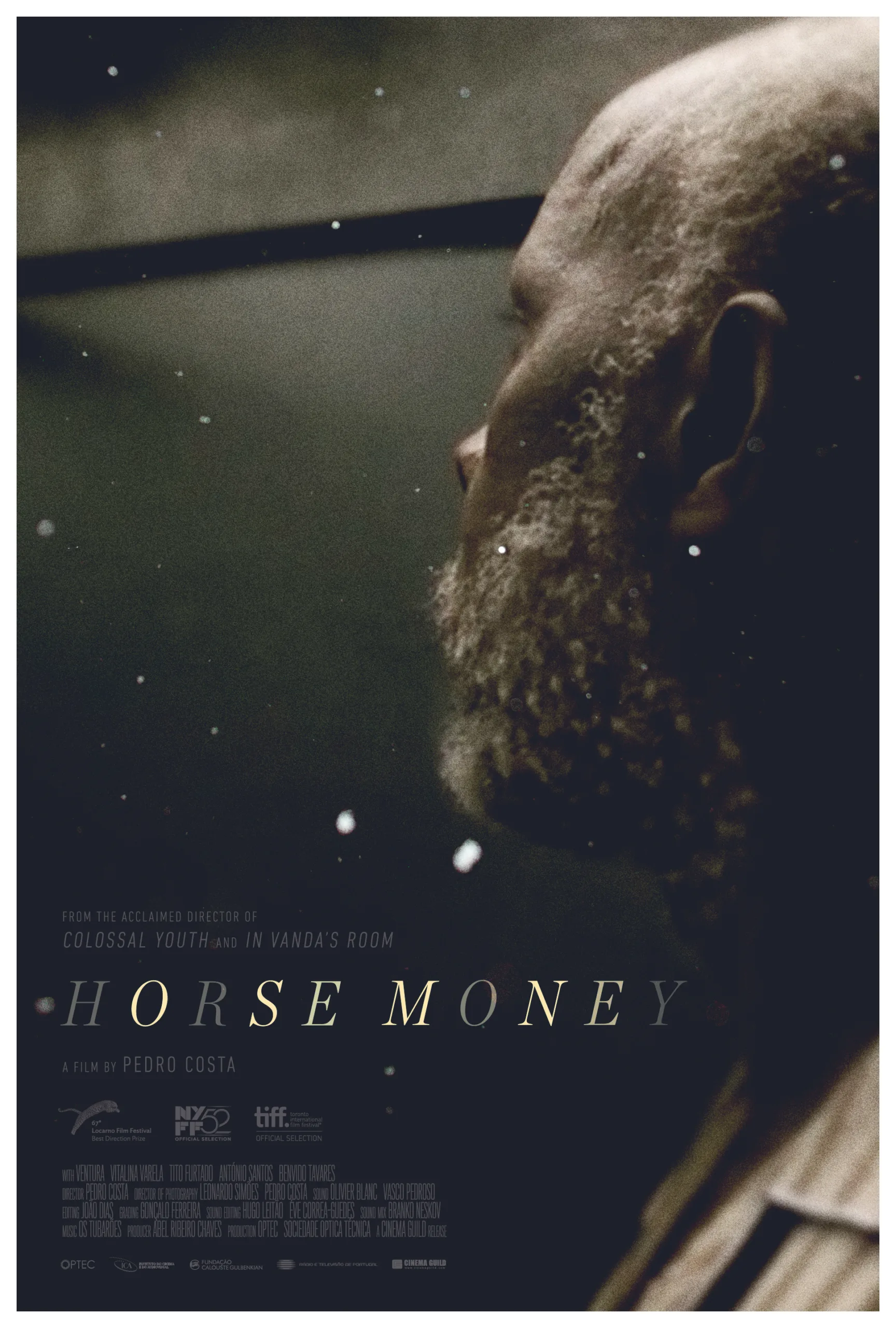

Even if there were, though, Costa’s filmmaking would’ve undercut it. He shoots Ventura’s face, and the faces of all the other actors, in tight closeups and in harshly lit long shots that emphasize the shapes of their bodies and the creases in their faces. Tears well up in Ventura’s eyes as he lingers in the pitch-black halls and rooms of an unnamed mental hospital, occasionally leaving and being brought back by authorities. There are other inmates in there with him. A group of inmates appears, materializes almost, by his bedside early on. They share their own life stories. They are laborers, criminals. They are the dispossessed, the oppressed.

Ventura is tripping down memory lane to such a degree that he seems to be suffering from dementia, but it might just be a Willy Loman or “The Singing Detective” type of situation—heavy on metaphorically ripe scenarios, but less affected than a stage play or time-jumping film might be, because the past is described verbally but not envisioned in flashback. In one scene, Ventura tells a doctor that he is a teenager and has been taken to the hospital by the the MFA, the Portuguese revolutionary army ended the African colonial war and won independence for Cape Verde. In a lot of Ventura’s monologues, he thinks he is 19, or that it’s 1975.

Costa’s compositions enfold him in the gloom of regretful memory as he speaks. He is visited by figures from his past, including Vitalina (Vitalina Varela), a woman who has returned to Lisbon from Cape Verde to bury her husband, who died three days earlier. Ventura assures her that her husband is “here with me,” but we aren’t sure how to take that. Here in the hospital? Here in Ventura’s heart? The movie is content with not knowing, even though the not-knowing may confuse or even infuriate the viewer. The film’s final stretch is dominated by Ventura’s ride in an elevator with a gun-toting soldier who never speaks. He just stands there like a statue. At times you aren’t sure if he’s alive. Are any of the characters alive?

You’ll see the word “dream” used a lot in descriptions of the movie. The stark, high-contrast cinematography aims for the sort of effect rarely conjured outside of a German Expressionist movie from the 1920s, or the noir-est of film noir, two modes that often posed their stories in someplace other than recognizable reality—a psychological space where feelings dictate the shape and texture of the frame and the way the characters behave within it. The title refers to a horse that was torn apart by vultures.

At points I was reminded of some of the most photographically stylized narrative features produced during Hollywood’s postwar era, including “My Darling Clementine” and “Moontide,” which have much more in the way of a traditional “story” than this but seem similarly inclined to let things unfold in a figurative space, one that is seemingly disconnected from any timeline or map even though the characters mention actual places and actual dates as they speak.

The rating at the top of this page is for originality and conviction, not for entertainment value, as if that phrase could mean anything when applied to such a gravely serious and mysterious movie. This is not a movie that comes to you. You have to go to it. There are long stretches of “Horse Money” in which you will have no idea what’s going on or how the movie wants you to take it, if indeed it wants you take it in any particular way, and on the basis of Costa’s past work, that seems unlikely. The best approach is to surrender to it as you might a dream and let the images overwhelm you.