It has always been a question whether “The Phantom of the Opera” (1925) is a great film, or only a great spectacle. Carl Sandburg, one of the original reviewers, underwent a change of heart between his first Chicago Daily News review (he waited for the Phantom’s unmasking “terribly fascinated, aching with suspense”) and a reconsideration written a month later (“strictly among the novelties of the season”). It was not, he added on the level of “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” or “Greed,” mentioning two of the greatest films of all time.

He was right about that, and could have added the greatest of all silent horror films, Murnau’s “Nosferatu” (1922), whose vampire may have influenced Lon Chaney’s performance as the Phantom. But as an exercise in lurid sensationalism, straining against technical limitations in its eagerness to overwhelm, the first of the many Phantom films has a creepy, undeniable power.

The story is simply told — too simply, perhaps, so that all of the adaptations, including the famous Andrew Lloyd Webber musical, have been much ado about relatively little. In the cellars of the Paris Opera House lives a disfigured masked man who becomes obsessed with the young singer Christine. He commands the management to give her leading roles, and when they refuse, he exacts a terrible revenge, causing a great chandelier to crash down on the audience.

Christine’s lover, a pallid nonentity, is little competition for her fascination with the Phantom, until she realizes with horror that the creature wants her to dwell in his mad subterranean world. She unmasks him, is repelled by his hideous disfigurement, flees to the surface and her lover, and is followed by a Phantom seeking violent revenge. There is no room for psychological subtlety here.

It is the idea of the Phantom, really, that fascinates us: the idea of a cruelly mistreated man going mad in self-imposed exile in the very cellars, dungeons and torture chambers where he was, apparently, disfigured in the first place. His obsession with Christine reflects his desire to win back some joy from a world that has mistreated him. Leroux and his adapters have placed this sad creature in a bizarre subterranean space that has inspired generations of set designers. There are five levels of cellars beneath the opera, one descending beneath another in an expressionist series of staircases, ramps, trapdoors, and a Styxian river that the Phantom crosses in a gondola. The Phantom has furnished his lair with grotesque fittings: He sleeps in a coffin and provides a bed for Christine in the shape of a whale boat. Remote controls give him warnings when anyone approaches and allow him to roast or drown his enemies.

To Christine, he offers wealth, luxury and opera stardom, and she is in no peril “as long as you do not touch the mask” — oh, and she must love him, or at least allow him to possess her (although his precise sexual plans are left undefined). Perhaps warned by the fate of the hero in her current production of “Faust,” she refuses this bargain, although for an engaged woman, she allows herself to be dangerously tempted.

After taking over the leading role from an ominously ill prima donna, she follows a mysterious voice, opens a secret door behind the mirror in her dressing room, descends through forbidding cellars, is taken semi-conscious by horseback and gondola deeper into the labyrinth and sees the coffin where he sleeps. At this point, her sudden cry of “You — you are the Phantom!” inspired me to write in my notes: “Duh!”

Her lover, the Viscount Raoul de Chagny, is likewise not a swift study. After the Phantom has presumably claimed dozens of victims with the falling chandelier and threatened Christine with death if she sees him again, Raoul agrees to meet her at the Masked Ball. This is held in the Opera House on the very next night, with the chandelier miraculously repaired and no mourning period, apparently, for the dozens of crushed and maimed. Christine tells Raoul the Phantom will murder them if they are seen together, but then, when a gaunt and spectral figure in red stalks imperiously into the grand hall, Raoul unmasks himself, which is, if you ask me, asking for trouble.

Christine determines to sing her role one more time, after which Raoul will have a carriage waiting by the stage door to spirit them safely away to England. This plan is too optimistic, as the Phantom snatches Christine from her dressing room, and the two are pursued into the bowels of Paris by Raoul and Inspector Ledoux — and, in a separate pursuit, by the vengeful stagehand Buquet (whose brother the Phantom murdered), leading a mob of torch-carrying rabble. The hapless Raoul and Ledoux are lured into a chamber where the Phantom can roast them to death, and when they escape through a trapdoor, it leads to a chamber where they can be drowned.

All of this is fairly ridiculous, and yet, and yet, the story exerts a certain macabre fascination. The characters of Christine and Raoul, played by Mary Philbin and Norman Kerry, essentially function as puppets of the plot. But the Phantom is invested by the intense and inventive Lon Chaney with a horror and poignancy that is almost entirely created with body language. More of his face is covered than in modern versions (a little gauze curtain flutters in front of his mouth), but look at the way his hand moves as he gestures toward the coffin as the titles announce “That is where I sleep.” It is a languorous movement that conveys great weary sadness.

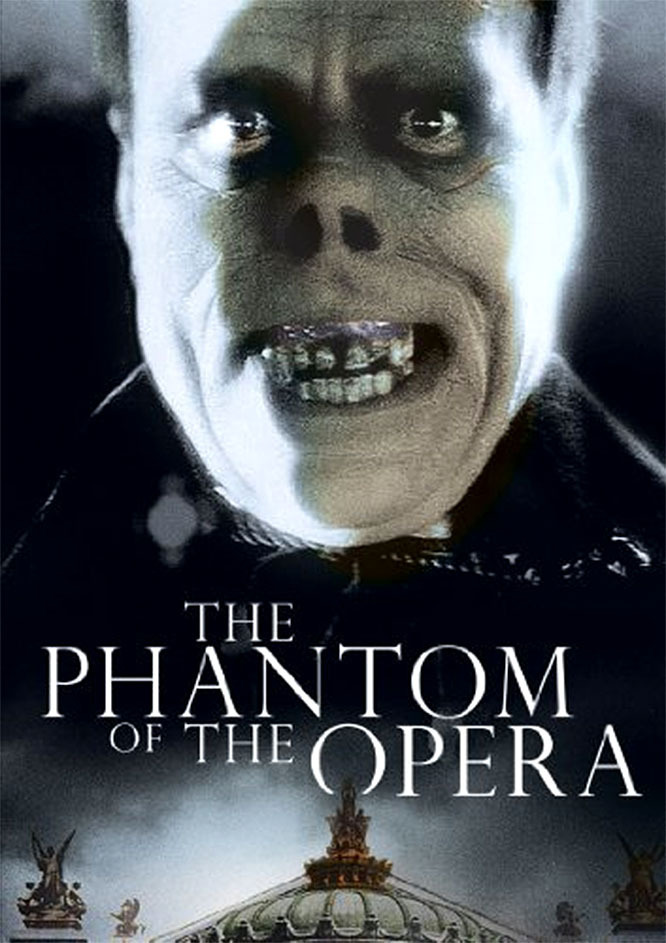

The Phantom’s unmasking was one of the most famous moments in silent film. He is seated at his organ. “Now, when he is intent on the music,” Sandburg wrote, “she comes closer, closer, her fingers steal towards the ribbon that fastens the mask. Her fingers give one final twitch — and there you are!” There you are, all right, as Chaney, “the Man of 1,000 Faces” and a master of makeup, unveils a defacement more grotesque than in any later version, his mouth a gaping cavern, his nose a void, his eyes widely staring: “Feast your eyes, glut your soul, on my accursed ugliness!”

The other famous scene involves the falling chandelier, which became the centerpiece of the Webber musical and functions the same way in Joel Schumacher’s 2004 film version. In the original film, it is curiously underplayed; it falls in impressive majesty, to be sure, but its results are hard to measure. Surely there are mangled bodies beneath it, but the movie stays its distance and then hurries on.

Much more impressive is the Masked Ball sequence and its sequel on the roof of the opera house. The filmmakers (director Rupert Julien, replaced by Edward Sedgwick and assisted by Chaney) use primitive color techniques to saturate the ball with brilliant scarlets and less obtrusive greens. Many scenes throughout the film are tinted, which was common enough in silent days, but the Masked Ball is a primitive form of Technicolor, in which the Phantom’s great red cloak sweeps through the air like a carrion bird that enfolds him.

And on the roof, as Raoul and Christine plot, he hovers unseen above them on the side of a statue, the red garment billowing ominously. Chaney’s movements in all of these scenes are filled with heedless bravado, and yet when he pauses, when he listens, when the reasons for his jealousy are confirmed, he conveys his suffering.

In a strange way, the very artificiality of the color adds to its effect. True, accurate and realistic color is simply … color. But this form of color, which seems imposed on the material, functions as a passionate impasto, a blood-red overlay. We can sense the film straining to overwhelm us. The various scores (I listened to the music by the great composer for silent film Carl Davis) swoop and weep and shriek and fall into ominous prefigurings, and the whole enterprise embraces the spirit of grand guignol.

“The Phantom of the Opera” is not a great film if you are concerned with art and subtlety, depth and message; “Nosferatu” is a world beyond it. But in its fevered melodrama and images of cadaverous romance, it finds a kind of show-biz majesty. And it has two elements of genius: It creates beneath the opera one of the most grotesque places in the cinema, and Chaney’s performance transforms an absurd character into a haunting one.

The new film version of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s “The Phantom of the Opera” opens nationally on Wednesday. See also the Great Movie reviews of “Nosferatu,” “The Man Who Laughs,” “The Fall of the House of Usher” and “Orpheus”.