For the ordinary filmgoer, and I include myself, “Ordet” is a difficult film to enter. But once you’re inside, it is impossible to escape. Lean, quiet, deeply serious, populated with odd religious obsessives, it takes place in winter in Denmark in 1925, in a rural district that has a cold austere beauty.

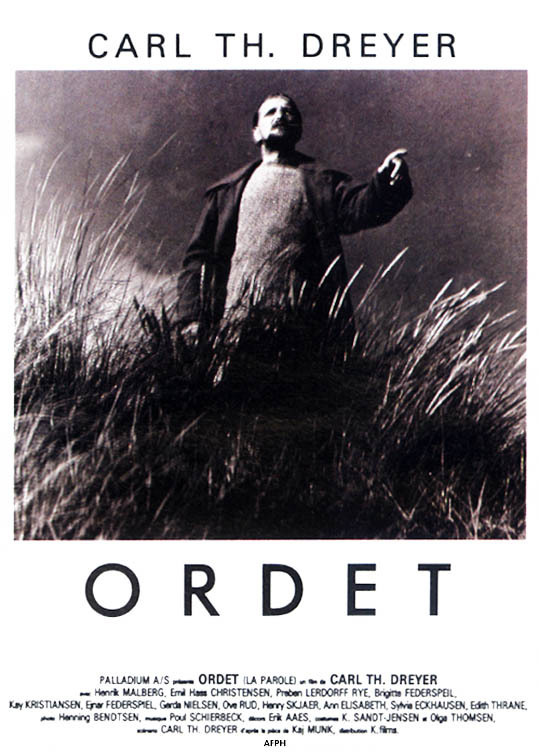

The film is one of only four major features by Carl Theodor Dreyer (1889-1968), who although he made many short films, was able to make only one feature each in the 1920s (“The Passion of Joan of Arc“), the 1940s (“Vampyr”), the 1950s (“Ordet”) and the 1960s (“Gertrud”). That was enough to place him first among all directors in the minds of such as Lars von Trier and the critic Jonathan Rosenbaum, and to make him (with Ozu and Bresson) the focus of Paul Schrader’s influential 1972 book Transcendental Style in Film. His “Joan of Arc” is often named among the 10 greatest films of all time.

But there are those who prefer “Ordet,” with its two families: those of Morten Borgen, patriarch of Borgensfarm, and those of Petersen, a nearby tailor. Morten is the bearded, stern father of three sons: The sincere Mikkel, married to Inger; the mad Johannes, who believes he is Jesus Christ, and the young Anders, a quiet youth who wants to marry the tailor’s daughter. The tailor, who works cross-legged sitting in his window, has a wife, Kirstin, and a daughter, Anne. The only other characters are Mikkel and Inger’s two young daughters, a pastor, a doctor, a midwife and a servant at Borgensfarm.

I take the time to name the characters because the movie takes time to establish them, to ground them all in the very fabric of the narrative. It does not dart from one to another. It gives each full weight. When they talk, it listens, and every word is measured, none glib or careless. It’s as if they’re talking for the record.

The early events seem ordinary enough. Inger is pregnant again. Anders has proposed to Anne. Morten is filled with pride in his farm, and his family is known by it: “The son of Borgensfarm,” etc. Anders confides to Inger that he wants to marry Anne, and Inger gently breaks this news to her father-in-law, but Morten will have none of it, because Peter the tailor is of the wrong religion. Both families are Christian, but Peter is of the fundamentalist belief, and Morten advocates a faith with more freedom and joy. In practice, both views translate to rigid dogmatism.

The unprepared audience member has long since grown a little restless, especially during the slow, mournful soliloquies of the mad Johannes, who regrets that the others do not follow him or heed his prophecies. There is a peculiar scene where the new pastor pays a call when only Johannes is at home, and listens to one of his dire monologues. When Morten returns, the pastor immediately shakes his hand and leaves. Why did he pay the call?

Doubt is expressed by Morten about the power of prayer, because his own could not save a loved one. He blames himself: “I did not truly believe.” Anders goes to Peter, asks for his daughter’s hand, and is turned down: “You are not a Christian.” Although Morten has refused to have his son marry the girl for exactly the same reason, the news that a son of Borgensfarm is not good enough for Peter’s daughter enrages him, and he sets off with Anders to the tailor’s house.

He interrupts the least cheerful prayer meeting I can imagine, with a small congregation hearing Peter’s confession that he is a sinner, now born again, and then joining in a doleful hymn. The congregation files out, the two old men sit down to discuss their differences and the futures of their children, and it is now, although we may not have noticed, that the film has taken its grip. We will not be able to look away again until the end, and we will think of nothing else.

Morten and Peter, played by Henrik Malberg and Ejnar Federspiel, sit side by side on a bench and brutally insult each other’s beliefs in deliberate, understated certainties. There is undeniable buried humor here. They have known each other for years. they know all of these disagreements already. Only at the end, when Peter goes too far, does Morten shake him by his shirt front.

These scenes are intercut with Inger going into labor back at the farm. The doctor, a tall, cool man, arrives to consult with the midwife. He intervenes to save Inger’s life. His work, shielded by a sheet, is so difficult that he bares his teeth in a grimace. This is the most painful scene of medical procedure I have ever experienced in a film, even though it is only suggested, not seen.

Now I will not tell you the rest of the story, at least not in so many words. Up to this point, I have practiced more description than “criticism,” because to closely observe this film is to criticize it, struggle with it, respond to it, understand it, and finally respect it. It is what it is, fearlessly, without compromise. Its characters lead their lives in their own ways, not for the convenience of the plot or the audience. They stand where they stand.

It turns out, after all, that some things are more important than others. That there are different kinds and depths of belief. That although all the adults except Johannes believe the Lord no longer works miracles, Morten may have been correct that a prayer must be believed to be successful. Dogma is meaningless without faith, but faith does not need dogma.

The lives of everyone in this film depend entirely on religion. It could be shown in any church in the world, with a few adjustments to the subtitles to supply other words than “Christian.” Yet I find from Rosenbaum that Dreyer was not a particularly religious man, and this film is not intended to proselytize. It simply intends to see.

That it does astonishingly well. The rude, simple sets have the solidity of a universe. The outdoor shots, of searches for the runaway Johannes on the moors, or a buggy ride across the horizon, are almost abstractly beautiful. Much is offscreen: The Borgensfarm sow that has had piglets is much watched, never seen. Peter’s house has only a sign and a doorway. The doctor’s car is established only by its headlights. The grim reaper is seen only by Johannes.

The camera movements have an almost godlike quality. At several points, such as during the prayer meeting, they pan back and forth slowly, relentlessly, hypnotically. There are a few movements of astonishing complexity, beginning in the foreground, somehow arriving at the background, but they flow so naturally you may not even notice them. The lighting, in black and white, is celestial — not in a joyous but in a detached way. The climactic scene could have been handled in countless conventional ways, but the film has prepared us for it, and it has a grave, startling power.

When the film was over, I had plans. I could not carry them out. I went to bed. Not to sleep. To feel. To puzzle about what had happened to me. I had started by viewing a film that initially bored me. It had found its way into my soul. Even after the first half hour, I had little idea what power awaited me, but now I could see how those opening minutes had to be as they were.

I have books about Dreyer on the shelf. I did not take them down. I taught a class based on the Schrader book, although I did not include “Ordet.” I did not open it to see what he had to say. Rosenbaum has written often about Dreyer, but when I quote him here, it is only things he has said to me. I did not want secondary information, analysis, context. The film stands utterly and fearlessly alone. Many viewers will turn away from it. Persevere. Go to it. It will not come to you.

Online in the Great Movies collection: “The Passion of Joan of Arc” and several titles by Ozu and Bresson.