There is such exhilaration in the heedless energy of the schoolboys. They tumble up and down stairs, stand on stilts for playground wars, eagerly study naughty postcards, read novels at night by flashlight, and are even merry as they pour into the cellars during an air raid. One of the foundations of Louis Malle‘s “Au revoir les enfants” (1987) is how naturally he evokes the daily life of a French boarding school in 1944. His central story shows young life hurtling forward; he knows, because he was there, that some of these lives will be exterminated.

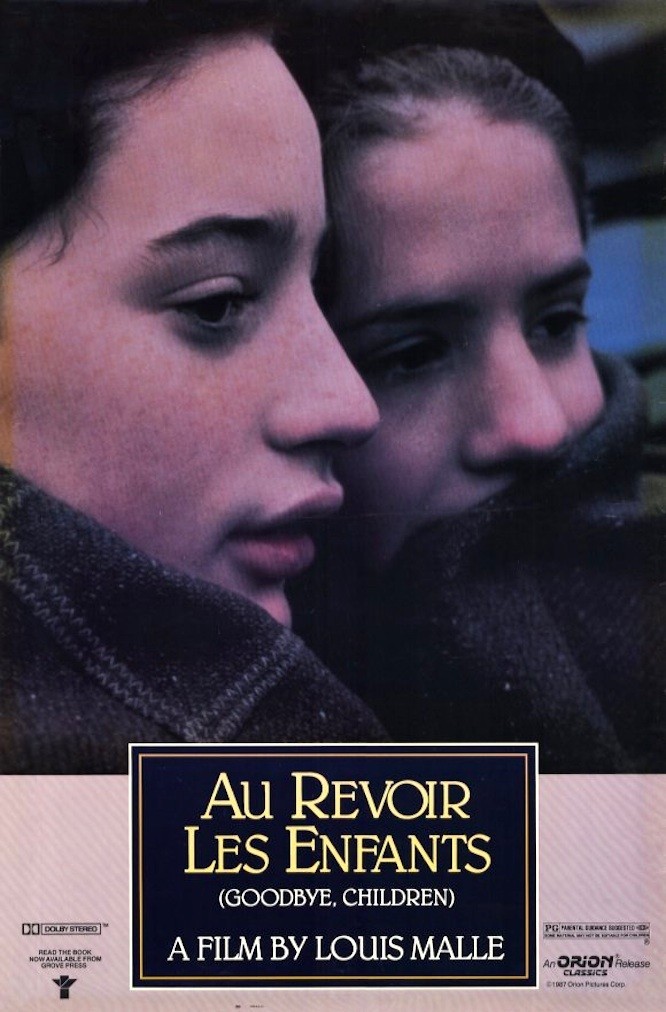

The film centers on the friendship of two boys of 12, Julien Quentin and Jean Bonnet. They are played by Gaspard Manesse and Raphael Fejto. They had never acted before and barely acted again. Julien’s father is always absent at his factory; his glamorous mother wants him safely away from Paris, and sends him by train to a Catholic school for rich children. Here he will find priests and teachers he respects, and classrooms where the students actually seem happy. One day after Christmas, a new student arrives: Jean.

Of course the others pick on the newcomer, and Julien joins in. Sometimes at that age fights are a form of expressing friendship, and often enough they end in laughter. They both love to read. Gradually, through a series of signs so subtle the other boys never pick up on them, Julian learns that Jean is concealing a secret. Is it the way he avoids questions about his family? The fact that he doesn’t recite the prayers with everyone else, and skips choir practice? Julien notices that when Jean kneels at the altar rail, the priest quietly passes without giving him a communion wafer. In Jean’s locker, Julien finds a book from which the name has not entirely been removed. The name is Kippelstein.

Julien knows almost nothing about Jews. “Why do we hate them?” he asks his older brother, Francois. “They’re smarter than we are, and they killed Jesus.” Julien doesn’t understand: “But it was the Romans who killed Jesus.” He does, however, feel some envy after he fails a piano lesson with the pretty Mlle. Davenne (Irene Jacob), and then Jean sits down and begins to play with ease and beauty. From time to time, the single awkward notes of Julien’s tortured piano lesson will be heard on the soundtrack, as when Jean gets a better essay score than Julien. When Julien sits for a long time in a bathtub, in closeup, we hear the notes again as the camera focuses on his face. We imagine he is piecing together everything he knows, and deciding to keep Jean’s secret.

It is near the end of the war. Marshal Petain’s collaborationist French government has lost popularity and an American invasion seems imminent. “Nobody likes Petain anymore,” someone says during parents’ weekend. Nazis patrol the district but are not always monsters. Julien asks his mother to invite Jean to join them and Francois at lunch, and when an old Jewish man at another table is confronted by French fascists, German officers at another table order them out of the room and tell the old man to continue with his meal.

In the film’s most important sequence, Julien is involved in a treasure hunt in a forest of deep shadows, large rock outcroppings and an ominous early twilight. He gets lost, and it feels a little like “Picnic at Hanging Rock.” He finds the treasure in a dark, hidden cave, and then he finds Jean. “Are there wolves in this forest?” Jean asks. They encounter a boar, who snuffles at them and waddles away. Walking home after curfew, they are seen by two Germans in a car. Jean begins to run, but the Germans catch both boys, give them a blanket to stay warm and return to them to the school. “You see, we Bavarians are Catholics also,” they say.

Yes, but the long day in the forest is the story of Julien’s year, the story of lost wandering, surrounded by unnamed dangers. He competes with the other students, is isolated, discovers a secret, and can share it with only one other student, Jean Bonnet. The two boys never talk about Julien keeping Jean’s secret; it doesn’t need saying. “Are you ever afraid?” Julien asks. “All the time,” says Jean.

“Au revoir les enfants” is based on a wartime memory of Louis Malle (1932-1995), who attended this very school, le Petit-College d’Avon, which was attached to a Carmelite monastery near Fountainebleau. The school, like many Catholic schools and other organizations, took in Jewish children under assumed names to shelter them from the Nazis; partly as a result, some 75 percent of French Jews survived the war, according to an essay by Francis J. Murphy.

Malle never forgot the day when Nazis raided the Petit-College and arrested three Jewish students and the headmaster (Father Jacques in life, Father Jean in the film). The students and their teachers lined up in the courtyard as the little group was marched off the grounds; the priest looked back at them and said, “Au revoir les enfants.” Goodbye, children. The three boys died at Auschwitz. The priest, whose birth name was Lucien Bunuel, nursed others and shared his rations at the Mauthausen camp, where he died four weeks after the war ended.

I remember the day “Au revoir les enfants” was shown for the first time, at the 1987 Telluride Film Festival. I had come to know Louis Malle a little since a dinner we had in 1972; he was the most approachable of great directors. I was almost the first person he saw after the screening. I remember him weeping as he clasped my hands and said, “This film is my story. Now it is told at last.”

Louis Malle was a pioneer of the French New Wave. His “Elevator to the Gallows” (1958) followed Jeanne Moreau through Paris using available light and a camera on a bicycle, which were then revolutionary techniques. His “The Lovers” (1958) and “Zazie in the Metro” (1960) were simultaneous with the other early New Wave films. Later in his career, he made powerful but more conventional narrative films like “Au revoir les enfants,” “Murmur of the Heart” (1971), “Pretty Baby” (1978) and “Atlantic City” (1980). His “Lacombe, Lucien” (1974), about a working-class youth who falls in with the Nazis, may have been inspired in part by the character of Joseph, the kitchen helper in “Au revoir.” As he gained worldwide success, Malle fell out of favor with some French critics because his films were popular and accessible, and also because he married Candice Bergen, although their love was true and she was his rock as he died in 1995 of lymphoma. Until the end, he was willing to experiment, as in “My Dinner With Andre” (1981), and the remarkable “Vanya On 42nd Street” (1994), a film about a rehearsal that Stanley Kauffmann thinks is the best Chekhov ever filmed.

It is difficult to say exactly what Malle thought Julien’s role (or his own) was in the capture of the Jewish students. In the film, a Nazi enters the classroom and demands to know if there are any Jews present. Julien unintentionally betrays Jean. I wrote in my original review: “Which of us cannot remember a moment when we did or said precisely the wrong thing, irretrievably, irreparably? The instant the action was completed or the words were spoken we burned with shame and regret, but what we had done never could be repaired.” Yes, but it is not clear that Julien is entirely responsible for Jean’s capture. “They would have caught me, anyway,” he tells Julien, giving him his treasured books.

The film ends in a long closeup of Julien, reminding us of the last shot of Truffaut’s “The 400 Blows,” and we hear Malle’s voice on the soundtrack: “More than 40 years have passed, but I’ll remember every second of that January morning until the day I die.” After the speech ends, the camera stays on Julien’s face for 25 more seconds, and on the soundtrack the piano is heard once again, this time quiet, sad and correct.