Some of the best moments in “Downhill Racer” are moments during which nothing special seems to be happening. They’re moments devoted to capturing the angle of a glance, the curve of a smile, an embarrassed silence. Together they form a portrait of a man that is so complete, and so tragic, that “Downhill Racer” becomes the best movie ever made about sports — without really being about sports at all.

The champions in any field have got to be, to some degree, fanatics. To be the world’s best skier, or swimmer, or chess player, you’ve got to overdevelop that area of your ability while ignoring almost everything else. This is the point we miss when we persist in describing champions as regular, all-round Joes. If they were, they wouldn’t be champions.

This is the kind of man that “Downhill Racer” is about: David Chappellet, a member of the U.S. skiing team, who fully experiences his humanity only in the exhilaration of winning. The rest of the time, he’s a strangely cut-off person, incapable of feeling anything very deeply, incapable of communicating with anyone, incapable of love, incapable (even) of being very interesting.

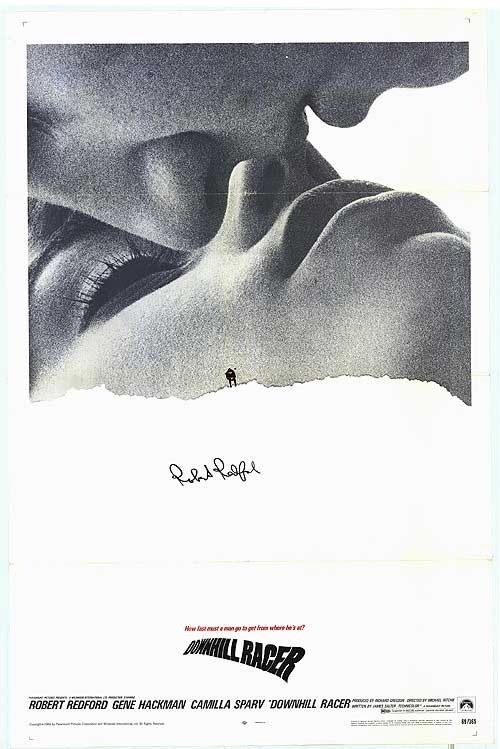

Robert Redford plays this person very well, even though it must have been difficult for Redford to contain his own personality within such a limited character. He plays a man who does nothing well except ski downhill — and does that better than anyone.

But this isn’t one of those rags-to-riches collections of sports clichés, about the kid who fights his way up to champion. It’s closer in tone to the stories of the real champions of our time: Sandy Koufax, Muhammad Ali, Joe Namath, who were the best and knew they were the best and made no effort to mask their arrogance. There is no humility at all in the racer’s character: Not that there should be. At one point, he’s accused by a fellow American of not being a good “team man.” Another skier replies: “Well, this isn’t exactly a team sport.”

It isn’t; downhill racing is an intensely individual sport, and we feel that through some remarkable color photography. More often than not, races are shot from the racer’s point of view, and there are long takes that nearly produce vertigo as we hurtle down a mountain. Without bothering to explain much of the technical aspect of skiing, “Downhill Racer” tells us more about the sport than we imagined a movie could.

The joy of these action sequences is counterpointed by the daily life of the ski amateur. There are the anonymous hotel rooms, one after another, and the deadening continual contact with the team members, and the efforts of the coach (Gene Hackman in a superb performance) to hold the team together and placate its financial backers in New York.

And there is Chappellet’s casual affair with a girl (Camilla Sparv), who seems to be a sort of ski groupie. She wants to make love to him, and does, but he is so limited, so incapable of understanding her or anything beyond his own image, that she drops him. He never does quite understand why.

The movie balances nicely between this level, and the exuberance of its outdoor location photography. And it does a skillful job of involving us in the competition without really being a movie about competition. In the end, “Downhill Racer” succeeds so well that instead of wondering whether the hero will win the Olympic race, we want to see what will happen to him if he does.