After seeing “Dead Man Walking,” I paused outside the screening to jot a final line on my notes: “This film ennobles filmmaking.” That is exactly what it does. It demonstrates how a movie can confront a grave and controversial issue in our society and see it fairly, from all sides, not take any shortcuts, and move the audience to a great emotional experience without unfair manipulation. What is remarkable is that the film is also all the other things a movie should be: absorbing, surprising, technically superb and worth talking about for a long time afterward.

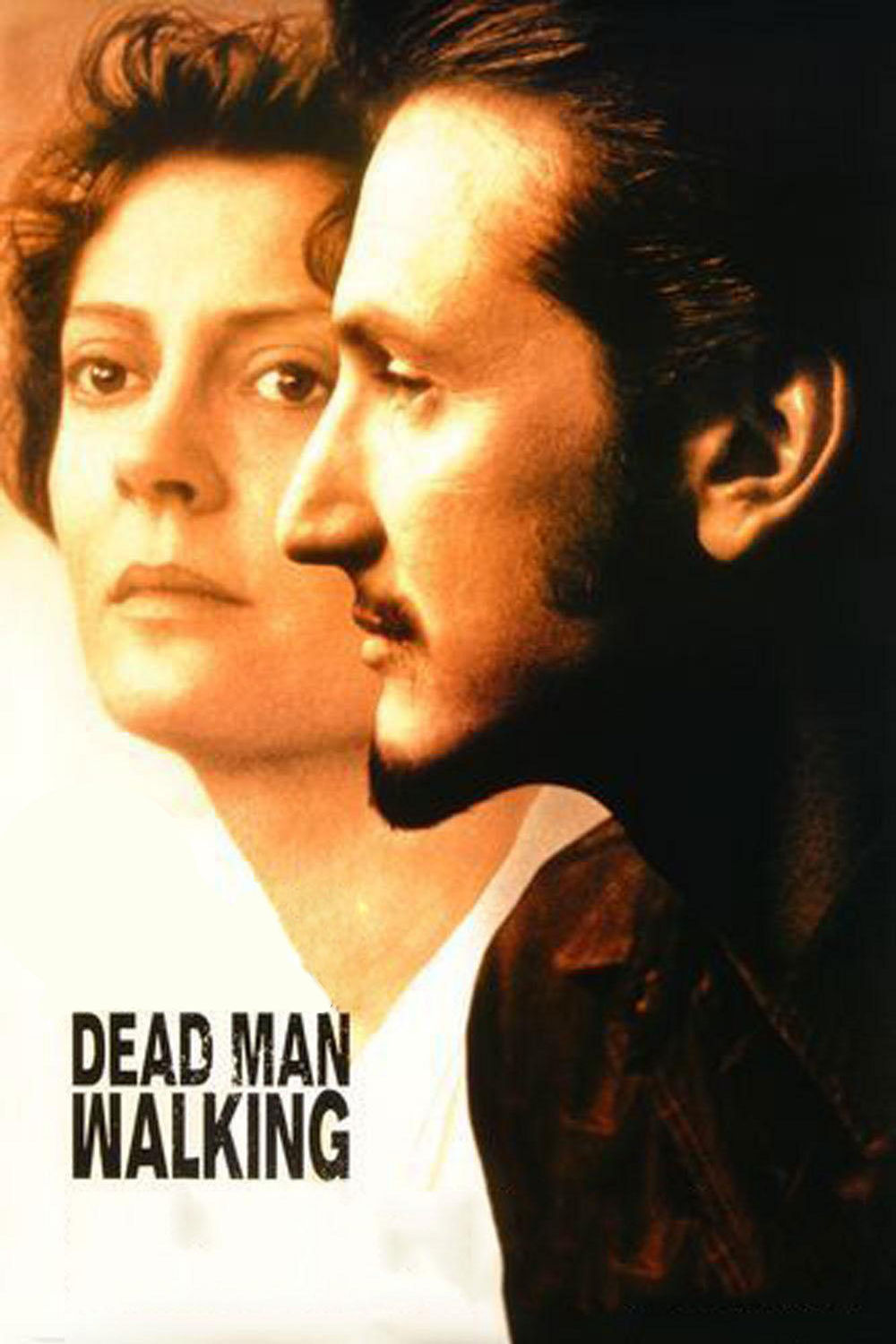

The movie begins with a Louisiana nun, Sister Helen Prejean (Susan Sarandon), who works in an inner-city neighborhood. One day she receives a letter from an inmate on Death Row, asking her to visit him. So she visits him. The prison chaplain (Scott Wilson) doesn’t think much of her visit, and briefs her on the ways that prisoners can manipulate outsiders. He obviously thinks of her as a bleeding heart. Her answer is unadorned: “He wrote to me and asked me to come.” The inmate, named Matthew Poncelet (Sean Penn), has been convicted, along with another man, of participating in the rape and murder of two young people on a lovers’ lane. We see him first through the grating of a visitor’s pen, so that his face breaks into jigsawlike pieces. In looks and appearance, he is the kind of person you would instinctively dread: He has the mousy little goatee and elaborate pompadour of a man with deep misgivings about his face. His voice is halting and his speech is ignorant. He smokes a cigarette as if sneaking puffs in a grade-school washroom. He tells her, “They got me on a greased rail to the Death House here.” He wants her to help with his appeal. At one point, he mentions that they don’t have anything in common. Sister Helen thinks about that, and says, “You and I have something in common. We both live with the poor.” His face looks quietly stunned, as if for the first time in a long time he has been confronted with an insight about his life that is not solely ego-driven. She says that she will come to see him again and that she will help him file a last-minute appeal against his approaching execution.

Sister Helen, as played here by Sarandon and written and directed by Tim Robbins (from the memoir by the real Helen Prejean), is one of the few truly spiritual characters I have seen in the movies. Movies about “religion” are often only that – movies about secular organizations that deal in spirituality. It is so rare to find a movie character who truly does try to live according to the teachings of Jesus (or anyone else, for that matter) that it’s a little disorienting: This character will behave according to what she thinks is right, not according to the needs of a plot, the requirements of a formula, or the pieties of those for whom religion, good grooming, polite manners and prosperity are all more or less the same thing.

But wait. The film is not finished with its bravery. At this point in any conventional story, we would expect developments along familiar lines. Take your choice: (1) The prisoner is really innocent, and Sister Helen leads his 11th-hour defense as justice is done; (2) They fall in love with one another, she helps him escape, and they go on a doomed flight from the law; or, less likely, (3) She converts him to her religion, and he goes to his death praising Jesus.

None of these things happen. Instead, Sister Helen experiences all of the complexities, contradictions and hard truths of the situation, and we share them. In movies like this you rarely see the loved ones of the victims, unless they are presented in hatefilled caricatures of blood lust. Here it is not like that.

Sister Helen meets the parents of the dead girl, and the father of the dead boy. (The father is seen among packing cases – moving, after a separation from his wife, who felt it was time for them to “get on with their lives,” which he can never do.) She begins to understand that Matthew may indeed have been guilty. She has to face the anger of the parents, who cannot see why anyone would want to befriend a murderer (“Are you a communist?”). There is a scene of agonizing embarrassment, as the girl’s parents make a basic mistake about her motives for visiting them.

And there is more. Matthew, we come to realize, is the product of an impoverished cultural background. He has been supplied with only a few cliches to serve him as a philosophy: He believes in “taking things like a man,” and “showing people,” and there on Death Row, he even makes a play for Sister Helen, almost as a reflex.

“Death is breathing down your neck,” she tells him, “and you’re playing your little man-on-the-make games.” He parrots a racist statement from his prison buddies in the Aryan Nation, which does his case no good, and later, when he bitterly resents his stupidity in saying those things, we realize he didn’t even think about them; nature abhors a vacuum, and racism abhors an empty mind and pours in to fill it.

The movie comes down to a drama of an entirely unexpected kind: a spiritual drama, involving Matthew’s soul. Christianity teaches that all sin can be forgiven, and that no sinner is too low for God’s love. Sister Helen believes that. Truly believes it, with every atom of her being. And yet she does not press Matthew for a “religious” solution to his situation. What she hopes for is that he can go to his death in reconciliation with himself and his crime. The last half-hour of this movie is overwhelmingly powerful – not the least in Matthew’s strained 11th-hour visit with his family, where we see them all trapped in the threadbare cliches of a language learned from television shows and saloon jukeboxes.

The performances in this film are beyond comparison, which is to say that Sarandon and Penn find their characters and make them into exactly what they are, without reference to other movies or conventions. Penn proves again that he is the most powerful actor of his generation, and, as for Sarandon, in film after film she finds not the right technique for a character so much as the right humanity. It’s as if she creates a role out of a deep understanding of the person she is playing.

Tim Robbins, Sarandon’s longtime companion, has directed once before (“Bob Roberts,” an intelligent political drama). With this film he leaps far beyond his earlier work and has made that rare thing, a film that is an exercise of philosophy. This is the kind of movie that spoils us for other films, because it reveals so starkly how most movies fall into conventional routine, and lull us with the reassurance that they will not look too hard, or probe too deeply, or make us think beyond the boundaries of what is comfortable. For years, critics have asked for more films that deal with the spiritual side of life. I doubt if “Dead Man Walking” was what they were thinking of, but this is exactly how such a movie looks, and feels.