From “Hitchcock/Truffaut” to “De Palma,” the film director has been a figure of fascination for documentarians as of late. For cinephiles, these auteur-focused documentaries hit a sweet spot—and for the newcomer, they can double as an introductory lesson in film studies.

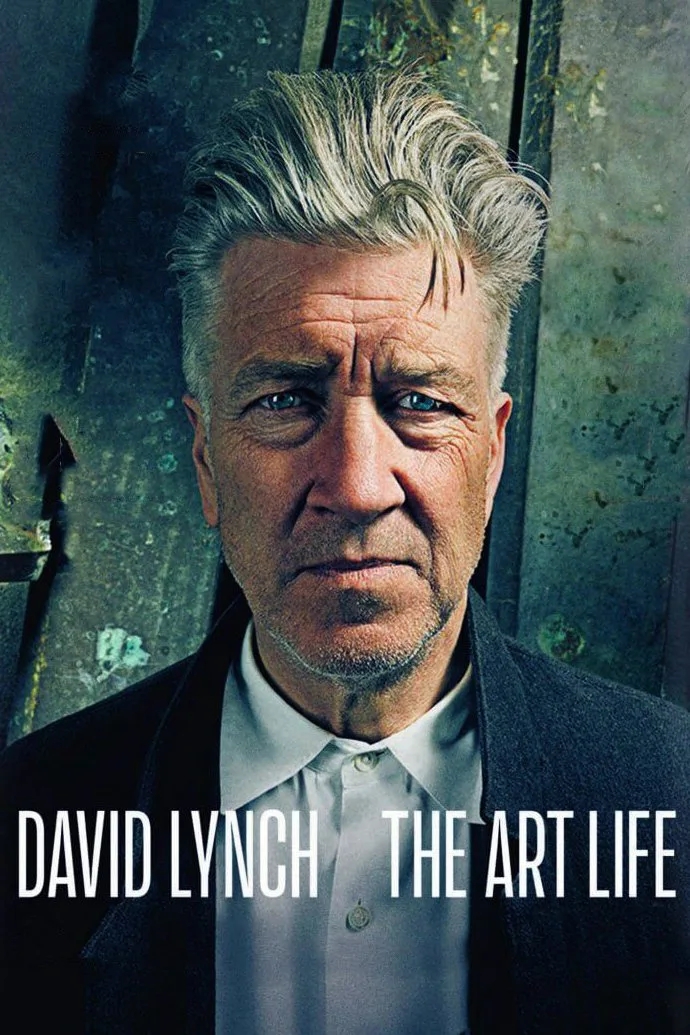

“David Lynch: The Art Life” may initially appear to be in the same vein as the aforementioned docs, but (much like the director himself) it’s of weirder and less accessible stock. Jon Nguyen’s film, made with a remarkable amount of cooperation and openness from the usually enigmatic Lynch, observes the man while he talks about his formative years, sloshes paint around in his studio in the Hollywood Hills, and plays with his toddler daughter, Lula.

Still, this is less a play-by-play of his film career than it is a look into Lynch’s lopsided worldview. Most of his major works, from “Blue Velvet” to “Mulholland Dr.,” are scarcely given a mention. Rather, the focus is on Lynch’s early life and the experiences which shaped him. He and his siblings grew up travelling from one pleasant middle-class suburb to the next for his father’s career as a research scientist. He grew up nervous, eccentric, and sensitive—an aspiring artist who bounced around East Coast cities and art schools without ever fully finding his niche. It wasn’t until he turned to film—winning an AFI grant to study and work in California—that the beginnings of what would be “Eraserhead” began to come to fruition.

As Lynch shares keenly-recalled adolescent memories in voice-over, Nguyen illustrates with a mixture of grainy 16mm footage from the director’s youth and contemporary film of the older Lynch pottering around in his studio. Also included are montages of Lynch’s sketches and paintings; often deeply disturbing and confessional. Painting was the director’s first passion and driving ambition. One day, apropos of nothing, he hallucinated that one of his paintings was “in motion”—and he was inspired to try out animation.

Hallucination seems like a fitting start to a film career like Lynch’s. And when the director speaks, one gets the sense that even his happiest childhood memories have the stain of the bizarre on them. Although Lynch describes a loving and traditional family upbringing in cheerfully bright Midwestern suburbs, his mind always seems to skew toward the shadow. At one point in the film, as he holds forth in his typically stilted manner, he tells a seemingly mundane anecdote. Before the Lynch family were moving away, they shared a sweet goodbye to their neighbors, the Smiths. But something suggests that their friendly idyll seems to have been broken. Mr. Smith was bidding them farewell, and then … “I can’t tell the story,” Lynch says mysteriously, mid-sentence. The way he finds the sinister in the most innocuous of stories is striking—largely because this is a prominent theme in so many of his films.

In another story, seemingly placed into “Blue Velvet” directly from memory, Lynch describes happily playing with friends on his neighborhood street when a woman—stark naked, hysterical, and bleeding from the mouth—emerged from the nearby woods and sat down on the curb nearby, weeping. Being children, they were frightened and unsure of where she came from—a local mental hospital, or some more terrible place of confinement and abuse? He describes the experience as “otherworldly”—and it’s not hard to imagine that such a jarring incident would stick out in anyone’s memory.

In spite of these stories, Lynch’s essence is still slippery and undefinable. He describes dark, fantastic dreams and big emotions from his younger years, or the rationale of his kind but straight-and-narrow parents, but, for the most part, the rest must be read between the lines. One of the more revealing moments comes when he describes his first weeks alone in an apartment before starting college in Boston. His apprehension about leaving the room became so great that he found himself paralyzed in a chair with only a transistor radio for company. He would get up to eat and then return to his seat—for a solid two-week stretch.

Clearly, these are not the sort of “movie magic” anecdotes we might get from Brian De Palma, laughing about the shoot-out scenes in “Scarface.” And for that reason, “The Art Life” may have a considerably narrower target audience. But this cockeyed, oblique attempt to get closer to the worldview of David Lynch—one of American cinema’s finest oddities—is a compelling slice of cinephile inquiry.