I know how I’m expected to feel when informed that a movie has been “based on a true story.” I’m supposed to feel solemn in the presence of a real person’s real experiences – which are, it is implied, somehow more significant and more authentic than the fictional adventures usually retailed on the screen.

And yet such words as “This is a true story” make my heart sink, because the movies so often use truth as a substitute for invention.

When a story sags or a character seems unlikely, the excuse of the “true story” always is the same: This really happened! Yes, but we are not at the movies because it really happened.

Unless we are members of Emmett Foley’s family, for example, how interested are we, really, in the fact that he was held unjustly in a mental hospital and courageously helped to expose its injustices? Not enough, I imagine, to set aside an evening of our time and several dollars for the ticket – unless, of course, the movie made of Foley’s experience is a good one. But its quality has nothing to do with its being based on “a true story.” What does it mean, anyway, “a true story”? Emmett Foley is not Gary Oldman, who stars in “Chattahoochee.” His wife was not Frances McDormand and his sister was not Pamela Reed, and it is quite likely that less than 5 percent of the dialogue in this movie actually was said in exactly the way the movie represents it. Nor can the events of many years be compressed into less than two hours without great liberties being taken with the “truth.” And yet I have little doubt that Mick Jackson, who directed the movie, and James Hicks, who wrote it, did a lot of research on the Foley case and scouted locations and hired people to make sure the women’s dresses reflected just what Southern women were wearing in the 1950s. The result is a movie that looks and feels authentic. And the performances – especially by Oldman, McDormand and Reed – are strong and well-textured.

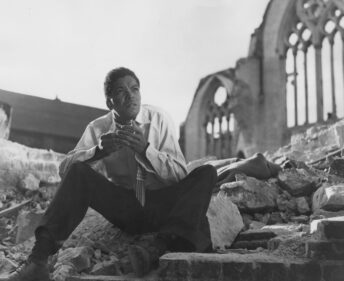

The Emmett Foley story begins in shabbiness, climbs to defiance, and ends in heroism. He was a Korean War veteran who became depressed by unemployment and decided to shoot up the neighborhood in the hopes that the cops would kill him and his wife could collect the insurance.

Instead, the cops captured him (SWAT teams were not such good shots in those days), and he was sent to Chattahoochee, a prison for the mentally ill that also was used as a catch-basin for the overflow from the regular prison population.

Conditions inside are reflected with gruesome faithfulness: the filth, the cockroaches, the illnesses, the beatings, the lack of any focus for a man’s hopes. At first Foley wants only to sink into oblivion. Then he gets mad, and with the encouragement of a friend (Dennis Hopper) he starts writing letters to the authorities, protesting conditions in the institution. When they take away his writing privileges (a denial of his constitutional rights), he starts recording outrages in the chapters of his Bible, and slips it to his sister during a visit.

The outcome is more predictable than stirring: A state commission is formed, hearings are held, outrage is stirred, Foley is vindicated, and the evil prison functionaries get their comeuppances. We know this will happen because it has happened before, in various ways, in movies like “The Snake Pit,” “One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest” and the Henry Fonda made-for-TV movie “Gideon’s Trumpet.” Isn’t it strange how real-life stories somehow seem to shape themselves into the form of fictional cliches? How, for example, Foley’s letters to the outside and Gideon’s letters to the outside would end in similar hearings? Here are some fictional accounts of prison life: Kafka’s “In the Penal Colony,” Dostoyevsky’s The House of the Dead, Cummings’ “The Enormous Room,” and Bresson’s film “A Man Escaped.” Perhaps because they are fiction, they contain truth in every word. They were not required to compromise in obedience to the facts.