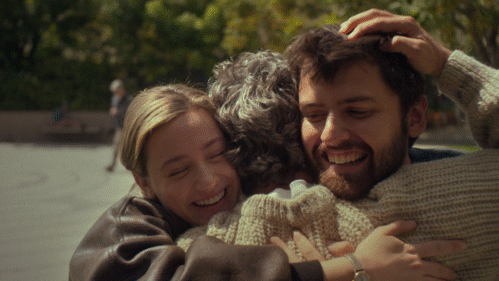

“Captain Fantastic,” written and directed by “Silicon Valley”‘s Matt Ross, presents a family who have retreated from the world into the wilderness of the Pacific Northwest. They are off the grid. They hunt for food. They are self-reliant. It’s “Swiss Family Robinson,” or that 1970s series of films about “The Wilderness Family.” Fresh air. No consumerism. No materialism. Okay, sounds fine, if a little unsustainable. Such utopias need a strong leader, and father Ben (Viggo Mortensen) is that. He treats his five kids as though they are military recruits (as well as PhD candidates). Because they are children, and because they are cut off from other influences, they parrot back to him his words, they share his worldview without question. It’s Family as Cult. All of this is extremely intriguing, calling to mind films like “The Mosquito Coast,” or “Running on Empty,” which had similar cloistered family atmospheres, and charismatic controlling (albeit well-meaning) fathers. But “Captain Fantastic” treats the situation (and Ben) so uncritically and so sympathetically that there is a total disconnect between what is actually onscreen and what Ross thinks is onscreen.

When the film opens, the mother of this little clan (Trin Miller’s Leslie) has been hospitalized for bipolar disorder, leaving Dad as “captain” of the ship. He puts the kids through fight training, boot camp drills and ushers his oldest son Bodevan (George MacKay) into manhood through the ritual of stalking and killing a deer solo. At night they sit around a campfire, the kids reading books like Guns, Germs and Steel, Middlemarch and Dostoevsky. They argue about capitalism and exploited classes, sounding like little robots, Bodevan informing his dad at one point, “I’m not a Trotsky-ist anymore. I’m a Maoist.” (This is a family where “Trotsky-ist” is descriptive and “Trotsky-ite” is an insult. It’s like it’s 1929 in the Soviet Union.) The kids miss their mother and want to know when she’s coming back. When Ben gets word that Leslie has killed herself, he informs the kids in blunt plain language.

Leslie’s parents blame Ben for everything and forbid him from coming to the funeral. Ben, who has set up his whole life so that he never has to answer to anyone, piles the kids into their gigantic school bus, and heads off to crash the funeral and make sure Leslie gets the Buddhist cremation ceremony she always wanted. It’s a long road trip. They pull off occasionally, once to steal supplies from a grocery store (they’ve run such drills before), and once for an annual family ritual: the celebration of Noam Chomsky Day. What will happen one day if one of the kids decides Noam Chomsky is full of it? Will that even be allowed? The irony here, and it is a terrible one, is that Ben is raising his kids to question the status quo, to not swallow any information wholesale, and yet he creates an environment where questioning his authority is impossible.

The family stops and stays the night with family (Kathryn Hahn’s Harper, Steve Zahn’s Dave and their two kids), and the culture clash is extreme. Ben’s kids don’t know anything about pop culture. To win the argument that his kids have been educated just fine without going to school, Ben forces his six-year-old to give an impromptu treatise on the Bill of Rights, the purpose of which is to shame the public-school cousins who have no idea about anything. The child rattling off facts about the Bill of Rights is supposed to be adorable and comedic as well as a “high five” moment for the family. I guess. It looked more like Ben was being a sanctimonious bully towards those who welcomed him into their home.

“Captain Fantastic” does acknowledge some of the issues in a character like Ben: Bodevan has to apply to college behind his dad’s back, and Rellian (Nicholas Hamilton) rebels openly against his father’s control. Rellian makes a choice at one point that feels like a victory and then he backtracks, apologizing to his father for disobedience. To his apology, Ben does not say, “I’m sorry too.” He says, “I love you.” It’s supposed to be touching. It’s not. Rellian is ten years old. He has nothing to apologize for. That’s the issue with “Captain Fantastic” in a nutshell.

“Captain Fantastic” is so soft on Ben that when Frank Langella shows up as Leslie’s father, and expresses outrage at the way Ben raises the children, he sounds like the voice of reason. And yet the film treats Langella as though he’s the villain, a self-satisfied Fat Cat, emblematic of everything Ben and his wife (and their drone-children) hate. (“Look at the unethical use of space!” chirps one of Ben’s daughters, looking at their grandfather’s backyard.)

The kids (Hamilton, MacKay, Charlie Shotwell, Shree Crooks, Samantha Isler, Annalise Basso) are all excellent, and create a believable family unit. Mortensen gives Ben’s authoritarian bent shadings of softness, openness, especially when he encourages his kids to think their thoughts through (forcing his daughter to go deeper in her literary analysis of Lolita is a nice little scene). Mortensen is a tremendously powerful actor, and he can do more in a closeup than most actors can with their whole bodies. It’s the attitude of the film that’s the problem.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau didn’t invent the idea of getting back to nature as the ultimate Good. It’s been with human beings since Adam and Eve frolicked in the garden. The thinking goes: If human beings could “get back to nature,” then maybe all the problems in the world could be eradicated. But there’s an error in that kind of thinking. Citizens of poverty-struck countries already live in a “natural” state, with no running water, subsistence agriculture, no modern medicine. They could probably tell the hippies a thing or two about how “nature” in its raw state is no great shakes, and a warm bed and a hot bath are nothing to sneeze at. But the mindset persists and it crosses ideological lines. There are the Amish and the Mennonites. There are the “survivalists,” holed up in compounds with their arsenals and conspiracy theories. There are the radical off-shoots of Christianity favoring homeschooling, and prioritizing being “in but not of” the world. Jonestown is the most dangerous example of what a retreat from the world can result in, but there are others with equally devastating consequences. Society isn’t the problem. Man is the problem. A utopia can only work if it’s made up of one person. The second another person shows up, you’re going to have problems.

If Ben were a “Jesus Camp” type, steeped in a political brand of Christianity, preparing his kids for apocalyptic Rapture, would his behavior be presented as adorably eccentric as it is here? Would a film present a survivalist-dad holed up with his kids and his weaponry as uncritically? It’s the same mindset, just different ideologies. Just because Ben is a lefty doesn’t mean he’s not a jerk. “Captain Fantastic” could have used a lot more skepticism.