Sandro do Nascimento is not merely poor, or hungry, or doomed to poverty, but suffers from the agonizing psychic distress of being invisible. Yes, says the movie, literally invisible: Brazilians with homes and jobs go about their lives while unable to see people like Sandro, who exists in a parallel universe.

In North America, we have similar blindness. One of the blessings of the Streetwise paper is that it provides not only income for its vendors, but visibility; by giving them a role, it gives us a way to relate to them — to see them, to nod, to say a word or two, whether or not we buy the paper.

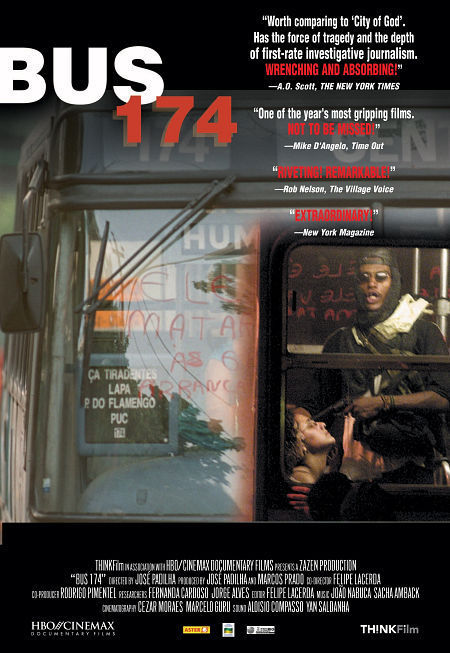

“Bus 174” opens with a news bulletin about the attempted robbery on the bus and then, as the bus is surrounded by police and the robber takes hostages, provides details about do Nascimento’s early life. He saw his mother stabbed to death in a robbery. His father was not in the picture. He lived on the streets and survived an infamous police massacre of homeless who used a downtown square as a sleeping area. He had been in jail. We listen to a social worker who talks of the boy’s dreams — of how he wanted to find a job and have a home.

Meanwhile, negotiations continue in the hostage situation. Several of the police who were involved (one hooded and his voice disguised) talk about their decisions and mistakes. After do Nascimento threatened to kill hostages — and after police for a time thought he had killed one –there were many opportunities for a sniper to take him out with one shot. He walked around in plain view, sometimes not close to his hostages, but the police didn’t act until the crisis reached a climax in the evening.

By that point in the film we know a lot about the human refuse of Rio’s streets. And we have seen one of the most horrifying sequences I’ve witnessed in a movie. The camera goes inside a crowded jail, where the prisoners press their faces against the bars and shout out their urgent protests against the inhuman conditions they endure. Cells are so crowded that the prisoners must live in shifts, half lying down while the other half stand. The temperature is over 100 degrees. The food is rotten, water is dirty, disease runs quickly through the cells, and some prisoners are left for months or years without charges being filed; they have been forgotten.

The director, Jose Padilha, films this scene with a digital camera, using the negative mode that switches black with white. The faces behind the bars cry out to us like souls in hell; nothing in the work of Bosch or the most abysmal horror films prepares us for these images. A nation that could permit these conditions dare not call itself civilized. Since prisoners are the lowest inhabitants of any society, how the society treats them establishes the bottom line of how it regards human beings. That prisons like this exist in Brazil makes it less surprising that the streets are filled with the lost and forgotten.

The conclusion of “Bus 174” is both surprising and inevitable. The bus hijacking captured the public’s attention in a way that dramatized the plight of the homeless, and the film, by documenting the conditions of Sandro de Nascimiento and countless others, shows that the journey began long before the passengers boarded the bus.

If you have seen the masterful 2002 Brazilian film “City of God” or the 1981 film “Pixote,” both about the culture of Rio’s street people, then “Bus 174” plays like a sad and angry real-life sequel. Fernando Ramos da Silva, the young orphan who played Pixote, died on the streets some years after the film was made, and do Nascimento in a sense stands for him — and for countless others.