Photographer William Claxton, who took so many memorable photographs of jazz trumpet legend Chet Baker, said in “Let's Get Lost,” Bruce Weber’s 1988 documentary about Baker, “It was the first time I learned what star quality meant, what charisma meant.” Claxton captured Baker in the season before heroin sunk in its claws, similar to Alfred Wertheimer’s famous 1956 photos of Elvis Presley: a star on the cusp, still untarnished. Robert Budreau’s “Born To Be Blue” is interested, refreshingly, in what Baker’s charisma meant and how it operated. Outside of talent, there was something about Baker’s image (the James Dean hair, the handsome angular face, the prominent jawline) that drew audiences in. His gifts as an artist aren’t in doubt, nor is his decades-long frank use of heroin, as well as the swoon to his death from a hotel window in Amsterdam in 1988, but unlike other biopics of famous drug-addled performers, “Born to Be Blue” tries to get at what, exactly, the Baker persona was all about. The film doesn’t frog-march us to the end of his life, obediently ticking off well-known events. Instead, it focuses on the period in the 1950s and 1960s when Baker became emblematic of what was known as West Coast jazz, an anomaly because of the color of his skin, but embraced (in some cases reluctantly) by the jazz giants of the day: Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, Charlie Parker. “Born to Be Blue” shows Baker gutting his way back after getting his front teeth knocked out in 1968 under mysterious circumstances.

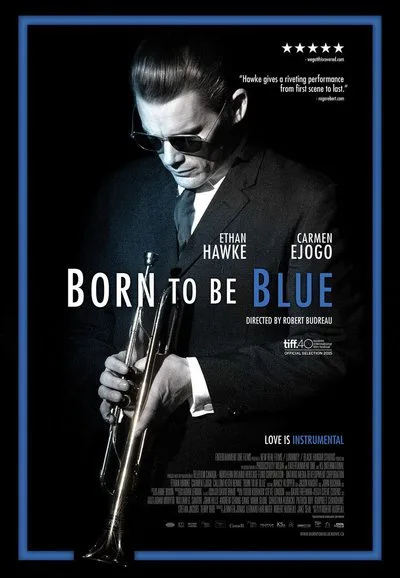

The film is carried by the performance of Ethan Hawke, a performance that understands Baker’s appeal, Baker’s demons and eventual unwillingness to fight those demons, as well as an exploration of the thing that was beyond Baker’s control (i.e. his charisma: it came naturally, a blessing and a curse.) “Born To Be Blue” has many of the elements familiar to music biopics, but it’s trying to do something different. It doesn’t always succeed, but the attempt is a welcome change.

As legend has it, producer Dino De Laurentiis approached Chet Baker when Baker was in dire straits in Europe, and expressed interest in developing a film about Baker’s life, starring Baker. De Laurentiis knew star quality when he saw it (and Baker had already appeared in a couple of films). That De Laurentiis project never came to pass, but “Born To Be Blue” presents an alternate history where it did. The film-within-a-film device is set up immediately in “Born to Be Blue,” where Baker is shown—in smudgy glamorous black-and-white evocative of the look of the famous documentaries of that era capturing folk and jazz festivals—acting out stories from his own life, including his introduction to heroin and a nerve-wracking triumphant performance at Birdland. These scenes are interrupted by backstage dramas, filmed in muted-old-Polaroids color, where Baker tries to get his music career back on track and connects romantically with his female co-star, an actress named Jane (Carmen Ejogo).

Jane is a fictionalized composite of various Baker women, and Jane the fictional actress is also playing a fictionalized composite in the film-within-a-film. The doubling-up that this represents, the mirror-reflections of unreality, adds to the sense that “Born To Be Blue” is interested in exploration as opposed to a rote presentation of biographical-details.

The film’s unique structure calls to mind a couple of recent unconventional biopics: Todd Haynes’ “I'm Not There” with its deep-dive into the persona of Bob Dylan, and Bill Pohlad’s gorgeous “Love & Mercy” about Brian Wilson, with its thrilling sequence showing the rigorous studio sessions for “Pet Sounds.” The problem with so many biopics is that the focus is on the star’s personal foibles, drug use, horrible relationships, arrests. The whole reason for the film—that the person’s art is important—is barely addressed. Why an artist is important or revolutionary is what should matter. Budreau cares about what Baker meant. One of the best sequences shows a small concert Baker gave in a recording studio, trying to re-assert himself after the loss of his teeth, where he sings “My Funny Valentine” with such a lonely private ache that time seems to stand still. In that sequence, even if you had never heard one of his songs, you can understand the obsession Baker still generates.

Ethan Hawke is a bit old to play the clean-cut heartthrob in the 1950s, but he brings to the role an almost terrifying sense of childlike susceptibility. The sensitivity that one hears in Chet Baker’s singing voice—its palpable romanticism, its endless sorrow—is understood by Hawke. Hawke’s startling openness, present from the very start of his career in “Dead Poets Society,” is weathered now, his face looks somewhat ravaged by worry, a wrinkle between his brows showing the anxiety of broken contracts with his younger self. It’s compelling just looking at him.

Carmen Ejogo gives a thoughtful intelligent performance (it’s a very well-written role). Their scenes together (especially a sex scene filled with rare vulnerability and communication) are complex; her character is filled out enough so that the talented Ejogo is not forced into the role usually given women in such films—the nag, the wet blanket, the long-suffering wife.

The film-within-a-film disappears at some point along the way, and Chet’s “reality” takes center stage. It’s a big disappointment. The device served as a “riff,” one of jazz’s distinguishing characteristics—a riff on Narrative and persona, a riff on the fact that one can’t really know the truth about anything. The device makes the distinction that what is happening onscreen is not necessarily factual yet it is a stab at truth. Truth is more important than facts. When “Born To Be Blue” leaves the film-within-a-film behind, it settles down into something more conventional, and the film misses that electric charge of unreality.

At one point in “Born To Be Blue,” Baker, on Methadone for heroin withdrawal, talks to Jane yearningly about what heroin provided his trumpet-playing: “Time gets wider … I can get inside every note.” It’s a great line. The film isn’t perfect, and in a lot of ways it doesn’t accomplish what it set out to do, but if you’re going to tell a story about Chet Baker you need to understand what it means to “get inside every note.” “Born To Be Blue” does.