`Black Robe” tells the story of the first contacts between the Huron Indians of Quebec and the Jesuit missionaries from France who came to convert them to Catholicism, and ended up delivering them into the hands of their enemies. Those first brave Jesuit priests did not realize, in the mid-17th century, that they were pawns of colonialism, of course; they were driven by a burning faith and an absolute conviction that they were doing the right thing. Only much later was it apparent that the European settlement of North America led to the destruction of the original inhabitants, not their salvation.

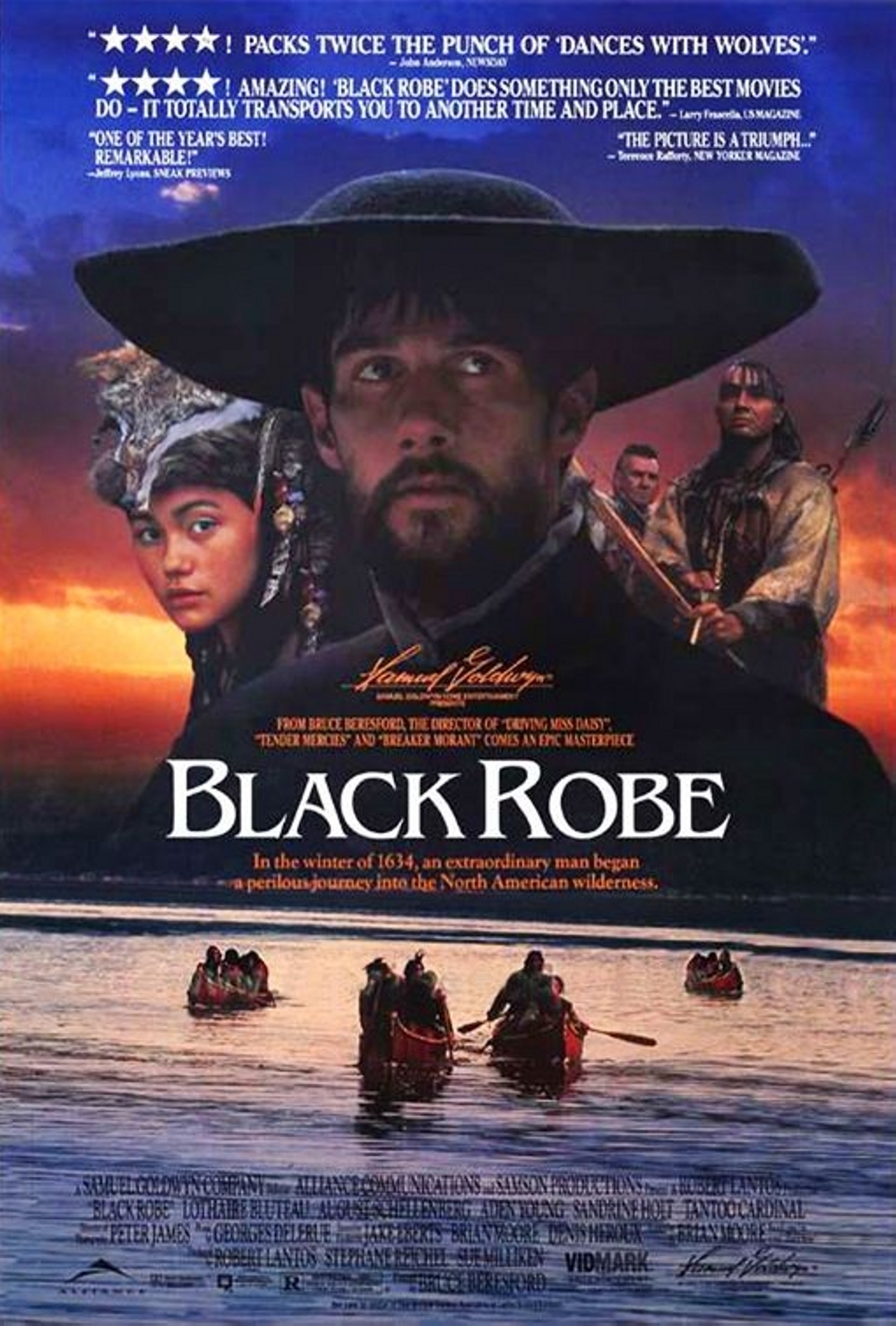

The film, a bleak and dour affair that seems filmed mostly under gray, glowering skies, stars Lothaire Bluteau in the central role of young Father Laforgue. Bluteau’s name may not ring a bell, but if you saw “Jesus of Montreal” you will recognize him immediately as the young actor who played the title role, gaunt and intense. In this film, he undertakes a long and arduous journey in winter, guided by the Algonquins, threatened by the Iroquois. It is a torturous experience, and “Black Robe” visualizes it in one of the most realistic depictions of Indian life I have seen.

The architectural details of the Indian dwellings, their methods of hunting and food procurement, the way they used absolute cooperation and trust of each other as a weapon against the deadly climate – these are all made clear in the movie. It also becomes clear that the Indians had their own religious and belief systems already in place, and that none of them had much use for Jesus and the other gifts of Christianity. The most pathetic character in the movie is a “converted” Indian, whose crucifix around his neck represents not a leap of faith, but an accommodation of convenience with those who could give him what he wanted.

The first contacts between North American Indians and Europeans were probably a great deal more like those depicted in “Black Robe” than like the stirring adventures in “Dances with Wolves.” Both sides were no doubt motivated much more by matters of religious belief and personal destiny than by a desire to get to know one another.

One of the achievements of “Black Robe,” which is based on research and a novel by Brian Moore, is that it re-creates a time when Christians were dogmatic and unswervingly convinced of their rightness; today, when we talk of the “fanaticism” of religions like Islam, we forget that the modern religions of the West, so diluted by psychobabble, were once fierce and righteous enough to send men halfway around the world seeking martyrdom.

Of all the Christian missionaries, the Jesuits were the most far-ranging and adventuresome. And they were everywhere, not only in Quebec, but in South America (see “The Mission”) and Japan (see “Shogun”). Movies about their exploits tend to romanticize them, however, and to fit their actions into the outlines of conventional movie plots. The reality was no doubt more like “Black Robe,” in which lonely men put their lives on the line in a test of faith, under conditions of appalling suffering and hardship.

Even granted these truths, however, “Black Robe” is a hard movie to enjoy. It was directed by Bruce Beresford, an Australian who seems to specialize in films about cultures in conflict. His credits include not only the famous “Driving Miss Daisy” and “Tender Mercies,” but also “The Fringe Dwellers,” a wonderful film about an Aborigine teenage girl in modern Australia, and “Mr. Johnson,” about an African who takes a job in a British colonial outpost, and finds he does not belong with either the British or his own people.

Mr. Johnson bears a strong resemblance to the accommodating Indian in “Black Robe,” who also leaves one group without finding a home in another. Perhaps that was the theme that attracted Beresford – the unhappy fate of those caught between cultures in irreconcilable conflict. He must also have been intrigued by the fate of Father Laforgue, the Bluteau character, who lacks the words to reason with another young Frenchman who falls in love with an Indian woman, and who has the will but perhaps not the strength to withstand the tortures of the Iroquois, when he and his companions are captured.

“Black Robe” is a film of enormous interest for those who care about the early history of Europeans in North America, but for ordinary moviegoers it will be very tough going. It is a much more rigorous and despairing work than a novel like Willa Cather’s Shadows on the Rock, which tells the story of the French in Quebec with serenity and an unshakable faith in human nature. And at the end, there is no deliverance.

I will not reveal the conclusion of the film, other than to say that when it was over, I sat there in a state of depressed suspension, wondering if that could possibly be all there was.

Matters were not helped by the words that appeared on the screen at the end, telling us what happened during the years to follow. It was as if the entire story of “Black Robe” was a prelude to nothing.