“Arlington Road” is a conspiracy thriller that begins well and makes good points, but it flies off the rails in the last 30 minutes. The climax is so implausible we stop caring and start scratching our heads. Later, thinking back through the film, we realize it’s not just the ending that’s cuckoo. Given the logic of the ending, the entire film has to be rethought; this is one of those movies where the characters only seem to be living their own lives, when in fact they’re strapped to the wheels of a labyrinthine hidden plot.

In the days when movies were made more carefully and were reluctant to insult the intelligence of their viewers, hard questions would have been asked at the screenplay level, and rewrites might have made this story more believable. But no. Watching “Arlington Road,” I got the uneasy feeling that the movie was made for (and by) people who live entirely in the moment–who gape at the energy of a scene without ever asking how it connects to what went before or comes after. It’s a movie that could play in “Groundhog Day;” it exists in the eternal present.

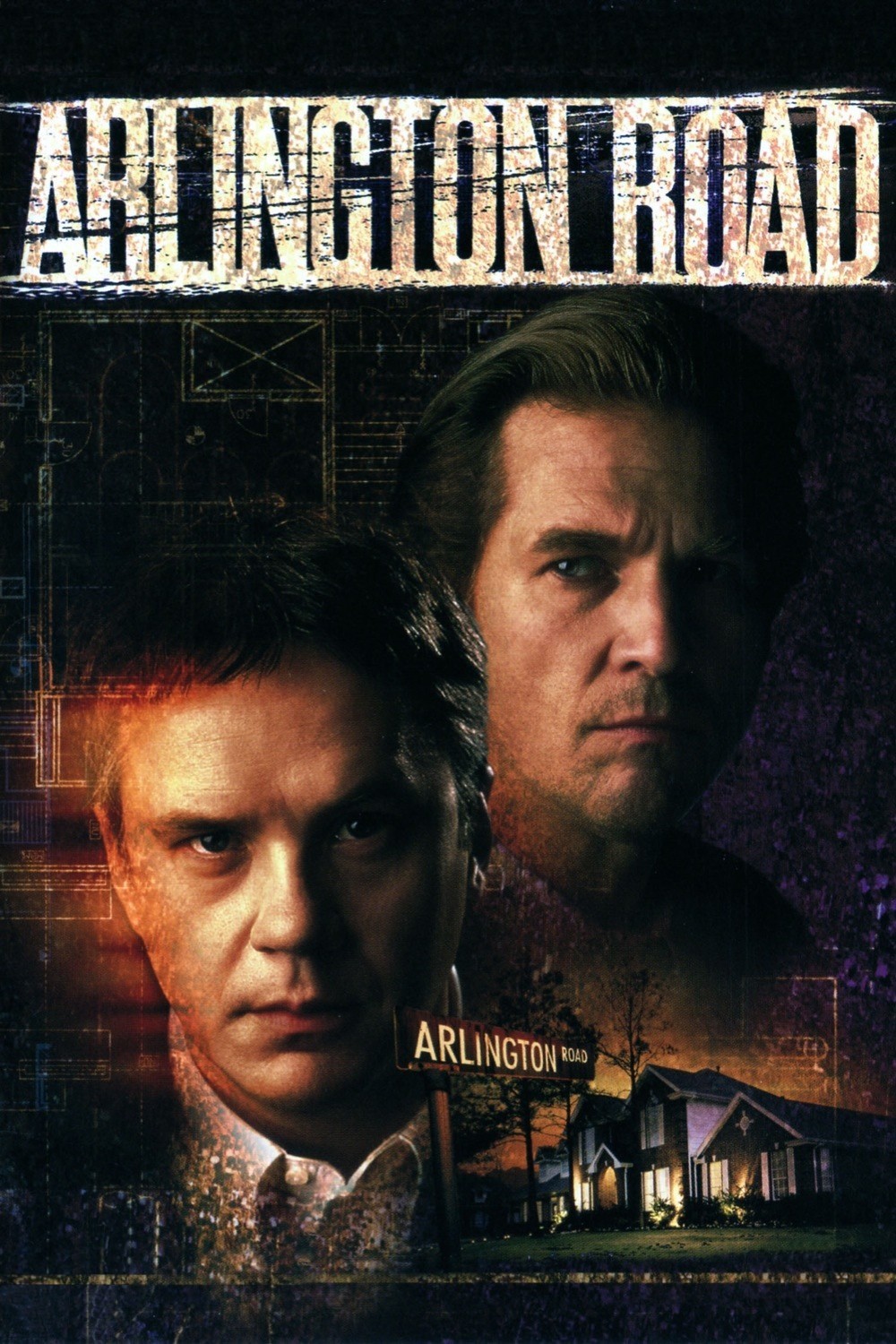

Jeff Bridges stars, as Michael Faraday, a professor of terrorism (no smiles, please), whose late wife was an FBI agent shot dead in a botched raid. Hitchcock would have made him an ordinary guy, and exploited the contrast with the weird plot he’s trapped in; but making him a professor lets the movie shoehorn in lots of info, as he lectures, narrates slide shows and takes his students on field trips.

Faraday’s key academic belief is that big terrorist events are not the work of isolated loners. We see photos of a federal building blown up in St. Louis, and hear his doubts about the official theory that it was the work of one man, who acted alone and died in the blast. “We don’t want others,” he tells his students. “We want one man, and we want him fast–it gives us our security back.” As the film opens, Faraday sees an injured kid wandering in the street. He races him to an emergency room, and later finds he is the son of some folks who have moved in across the street: Oliver and Cheryl Lang (Tim Robbins and Joan Cusack). Faraday and his girlfriend, a graduate student with the wonderful movie name of Brooke Wolfe (Hope Davis), grow friendly with the Langs. But then Faraday, who like all terrorism professors no doubt has a streak of paranoia, begins to pick up little signals that the Langs are hiding something.

His investigation into Lang’s background is hard to accept, depending as it does on vast coincidences. (After he finds an old newspaper article about Lang on the Internet, he journeys to a library and looks up the same material on old-fashioned microfilm, just so Lang can come up behind him and see what he’s reading.) To be fair, some of the implausibilities in this stage of the movie can be explained once it is over and we rethink the entire plot.

But leave the plot details aside for a second. What about the major physical details of the final thriller scenes? How can anyone, even skilled conspirators, predict with perfect accuracy the outcome of a car crash? How can they know in advance that a man will go to a certain pay phone at a certain time, so that he can see a particular truck he needs to see? How can the actions of security guards be accurately anticipated? Isn’t it risky to hinge an entire plan of action on the hope that the police won’t stop a car speeding recklessly through a downtown area? It’s here that the movie completely breaks down. Yes, there’s an ironic payoff, and, yes, the underlying insights of the movie will make you think. But wasn’t there a way to incorporate those insights and these well-drawn, well-acted characters into a movie that didn’t force the audience to squirm in disbelief? “Arlington Road” is a thriller that contains ideas. Any movie with ideas is likely to attract audiences who have ideas of their own, but to think for a second about the logic of this plot is fatal.