The makers of the based-on-a-true-story black comedy “American Made” fail to satisfactorily answer one pressing question: why is CIA operative and Colombia drug-runner Barry Seal’s story being told as a movie and not a book? What’s being shown in this film that couldn’t also be expressed in prose?

In telling the true story of American airplane pilot Barry Seal (Tom Cruise), writer Gary Spinelli and director Doug Liman (“Edge of Tomorrow,” “Jumper“) choose to overstimulate viewers rather than challenge them. They emphasize Barry’s charm, the exotic nature of his South American trade routes, and the rapid escalation of events that ultimately led to his downfall. Cruise’s smile is, in this context, deployed like a weapon in Liman and Spinelli’s overwhelming charm offensive. You don’t get a lot of psychological insight into Barry’s character, or learn why he was so determined to make more money than he could spend, despite conflicting pressures from Pablo Escobar’s drug cartel and the American government to either quit or collude.

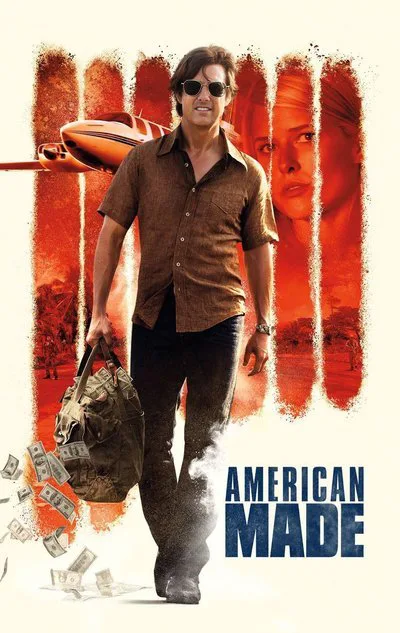

But you do get a lot of shots of Cruise grinning from behind aviator glasses in extreme close-ups, many of which are lensed with hand-held digital cameras that show you the wilds of Nicaragua and Colombia through an Instagram-cheap green/yellow filter. “American Made” may be superficially a condemnation of the hypocritical American impulse to take drug suppliers’ money with one hand and chastise users with the other. But it’s mostly a sensational, sub-“Wolf of Wall Street”-style true crime story that attempts to seduce you, then abandon you.

The alarming pace of Barry’s narrative, designed to put Cruise’s charisma front and center, keeps viewers disoriented. It’s often hard to understand Barry’s motives beyond caricature-broad assumptions about his (lack of) character. In 1977, Barry agrees to fly over South American countries and take photos of suspected communist groups using a spy plane provided by shadowy CIA pencil-pusher Schafer (Domhnall Gleeson). Barry is impulsive, or so we’re meant to think based on an incident where he wakes up a sleeping co-pilot by abruptly sending a commercial airliner into a nosedive. This scene may explain why Barry grins like a lunatic as he explains to his wife Lucy (Sarah Wright) that he’ll figure out a way to pay out of pocket for his family’s health insurance once he opens an independent shipping company called “IAC” (Get it? IAC – CIA?).

Barry’s impetuousness does not, however, explain why he flies so low to land when he takes his photographs. Or why he doesn’t immediately reach out to Schafer when he’s kidnapped and forced by Escobar (Mauricio Mejia) and his Cartel associates to deliver hundreds of pounds of cocaine to the United States. Or why Barry thinks so little of his wife and kids that he packs their Louisiana house up one night without explanation, and moves them to a safe-house in Arkansas. There’s character-defining insanity, and then there’s “this barely makes sense in the moment when it is happening” crazy. Barry often appears to be the latter kind of nutbar.

There are two types of people in “American Made”: the kind that work and the kind that get worked over. It’s easy to tell the two apart based on how much screen-time Spinelli and Liman devote to each character. Schafer, for example, is defined by the taunts he suffers from a fellow cubicle drone and his own tendency to over-promise. Schafer doesn’t do real work—not in the filmmakers’ eyes. The same is true of Escobar and his fellow dealers, who are treated as lawless salesmen of an unsavory product. And don’t get me started on JB (Caleb Landry Jones), Lucy’s lazy, Gremlin-driving, under-age-girl-dating, Confederate-flag-waving redneck brother.

But what about Lucy? She keeps Barry’s family together, but her feelings are often taken for granted, even when she calls Barry out for abandoning her suddenly in order to meet up with Schafer. Barry responds by throwing bundles of cash at his wife’s feet. The argument, and the scene end just like that, like a smug joke whose punchline might as well be, There’s no problem that a ton of cash can’t solve.

“American Made” sells a toxic, shallow, anti-American Dream bill of goods for anybody looking to shake their head about exceptionalism without seriously considering what conditions enable that mentality. Spinelli and Liman don’t say anything except, Look at how far a determined charmer can go if he’s greedy and determined enough. They respect Barry too much to be thoughtfully critical of him. And they barely disguise their fascination with broad jokes that tease Barry’s team of hard-working good ol’ boys and put down everyone else.

Sure, it’s important to note that Barry ultimately meets a just end, one that’s been prescribed to thousands of other would-be movie gangsters. But you can easily shrug off a little finger-wagging at the end of a movie that treats you to two hours of Tom Cruise charming representatives of every imaginable US institution (they don’t call in the Girl Scouts, the Golden Girls or the Hulk-busters, but I’m sure they’re in a director’s cut). If there is a reason, good or bad, that “American Made” is a movie, it’s that you can’t be seduced by the star of “Top Gun” in a book.