Last year a very unusual movie came out of China called “Paths of the Soul.” One thing that was unusual about it was that Chinese censors didn’t stamp on a movie that portrayed Tibet, and Tibetan Buddhism, in a positive light. Another was the movie’s subject, an over 1,000 mile journey by foot undertaken by a group of poor Tibetans, a pilgrimage to visit some of their religion’s most holy sites. It was inspiring, moving, sometimes funny. It was hard to imagine a similar journey taking place in the States.

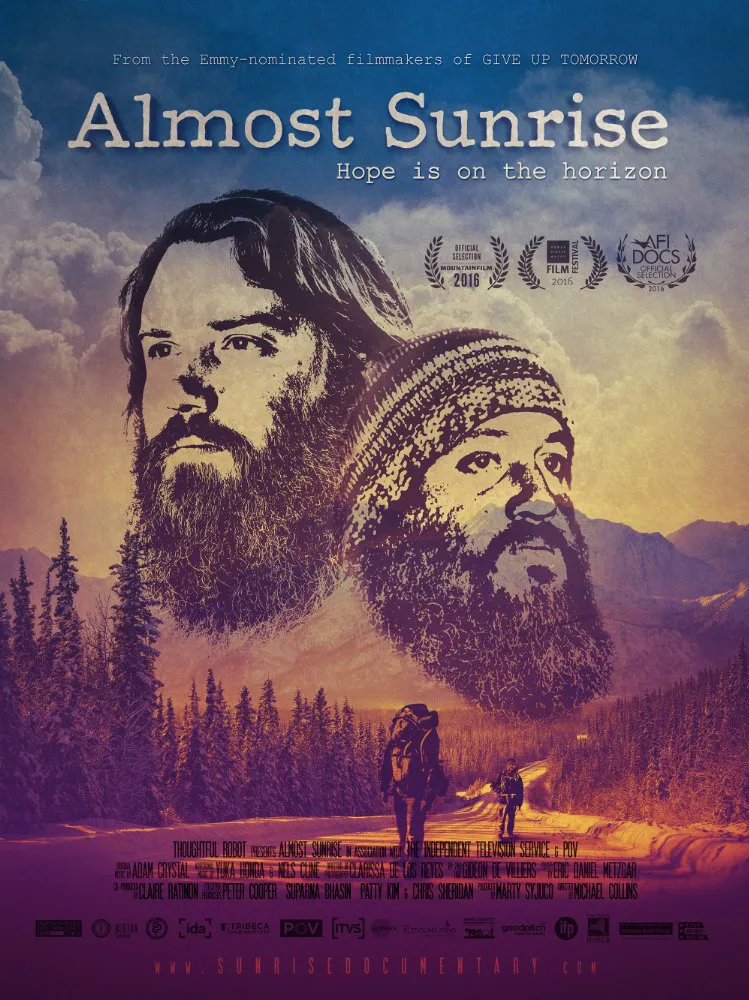

“Almost Sunrise,” a picture credited as by Michael Collins and Marty Syjuco (Collins directed, Syjuco is one of the producer) tells of an even longer walk, from a war memorial in Milwaukee Wisconsin to California, undertaken by two Iraqi war vets. It is in a very real sense a spiritual journey, but one of healing rather than worship. The movie begins with a definition of “Moral Injury.” It is, according to the onscreen text, “a wound to the soul” caused by committing acts “against our sense of right and wrong.” The movie begins with Tom Voss, over video footage of him waving flags as a child in the early ‘80s, saying “I have a lot of military history in my family.” In his home town of Milwaukee, nine years after his return from the war in Iraq, the movie shows a boarded-up building with signs in the window reading “Peace In Our City” and “Peace In Our Selves.” After Tom tells his story of an inability to find the latter, the movie shifts to fellow vet Anthony Anderson, whose big brown beard gives him a resemblance to Tom. He tells the camera, “I don’t want people to be around me so I make it intolerable for people to be around me.” He looks for help, but notes, “The VA as an institution sucks. Because they make mistakes and say it’s your fault.” Around this point the movie tells us that 20 veterans a day commit suicide.

Tom and Anthony, we are meant to understand, undertake their journey to California as a way to keep themselves alive. Their early days on the road are frustrating. Anthony tears up one of his feet trying to walk too far. But eventually the fellows hit a groove, and in each state they cross, there are veterans and other well-wishers to greet them. They spend a long time speaking to each other. “How can a just God let humans do this to each other,” one of the veterans says, after recounting the horrors of a particular firefight. (The movie interpolates a good deal of video footage shot in Iraq with the veterans’ state-to-state trek.) In a striking desert setting they meet a Native American vet, dressed in full ceremonial gear, for an exchange of perspectives. By the time they reach the water at the end of Santa Monica Boulevard, having been joined on the last seven miles of the journey by a combat mate of Tom’s, what have they achieved. Anthony speaks of having had “some level of faith in people” restored to him. But Tom, while not doubting the trip’s value, particularly in bringing awareness of profound veterans’ issues to light, bluntly says “By no means did I think that I was better.”

So the movie continues to follow both Tom and Anthony as they search for healing by other means. Tom’s visit to a religious retreat and exposure to a method of therapy works some wonders on him. The movie then goes on to make a strong point about PTSD and “moral injury,” and the distinctions between the two. I found the case compelling. Some others may not. But “Almost Sunrise” presents a journey that is very much worth the time of anyone who’s concerned about the effect war has on our brothers and sisters who fight—which should translate to “everyone.”