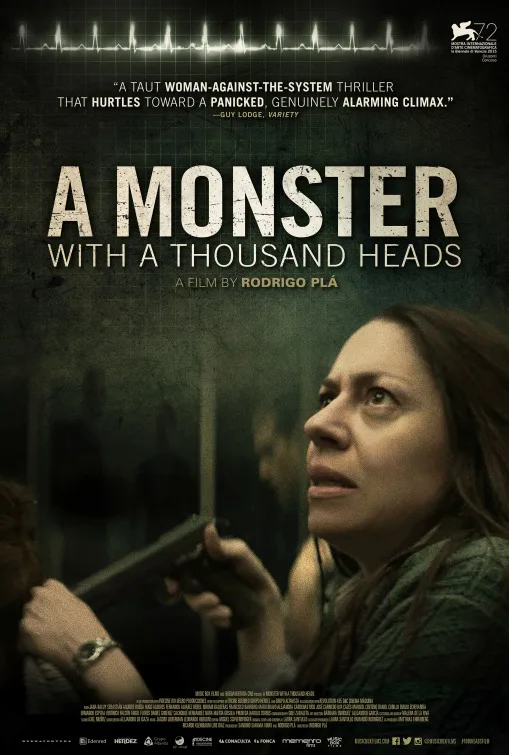

Although Rodrigo Plá’s “A Monster With a Thousand Heads,” about a woman who resorts to desperate measures against an insurance company that refuses to cover her husband’s treatment, can conveniently be categorized as a thriller, it’s one of those films that shouldn’t be pigeonholed with a plot synopsis or a genre tag. The movie deserves to be known, first of all, as a terrific example of intelligent, captivating film craft—further proof of the recent strength of Mexican cinema.

“A Monster with a Thousand Heads” grabs you with its first shot. Although there’s something visible on the screen’s right side, the image is so dark that I wondered briefly if there was something wrong with the print or the projection. But there’s no problem; the image’s darkness—which soon clarifies that this is the bedroom of the protagonist’s husband—serves mainly to draw our eyes into the picture, one of a number of unexpected techniques that make the film so visually entrancing throughout.

Once we’re in that bedroom, the plot’s premise is sketched in quickly and subtly. Mexico City housewife Sonia (Jana Raluy, a stage actress who contributes brilliant work here) is doing everything she can to take care of her husband Guillermo, who’s bedridden with ever-worsening cancer. Though he keeps up a brave front, it’s clear he’s in considerable pain, and she soon realizes—after pouring through sheaves of medical data—that he needs a kind of treatment that his insurance company should okay but hasn’t.

She first off goes to the office of the doctor whose approval is necessary, where she’s given an insulting, aggravating runaround. She waits for hours, then is told the doctor has gone for the day. He hasn’t, though, and when she realizes that, she goes in angry pursuit.

Before she catches up with him, Dr. Villalba (Hugo Albores) exits the office into an underground car park with a younger colleague. In most movies, our attention would remain with Villalba, of course. But Plá puts his camera in the backseat of the car of the younger man, who mutters insults against his colleague as he turns on his headlights, loud music blasts from his stereo and we watch Villalba through the windshield. This kind of startling move, which shifts our perspective momentarily from the main characters to a secondary one, is an imaginative device that Plá uses to fine effect throughout.

Accompanied by her disbelieving teenage son Darío (Sebastián Aguirre, who gave an equally fine deadpan performance in last year’s “Güeros”), Sonia tracks down Villalba, and soon enough they are tracking down insurance company executives—over a weekend when they are both difficult to find and disinclined to be disturbed. The gist of what eventually emerges is that some of those responsible for assigning coverage are pressured by higher-ups to deny it to a certain number of clients, whether they’re entitled to it or not; that’s what has happened to Sonia’s husband.

Is this a common situation in Mexico—or for that matter, the United States? The screenplay here is by Laura Santullo, based on her novel, and neither the film nor its press notes give any information regarding the story’s factual background. But the basic, Kafkaesque idea of an ordinary individual up against a giant, uncaring bureaucracy is familiar enough to give the tale a very credible emotional charge.

Some ways into the story, we begin hearing commentary on it that evidently is testimony in a trial (Sonia’s?) that happens after the events we witness. This adds another layer of complexity—while simultaneously adding certain dollops of information—to Plá’s ingenious narrative and visual strategies. Also, at the one point, Sonia begins brandishing a pistol, which heightens the tension while moving us further into genre territory.

Yet, though increasingly gripping, the film never feels like a conventional thriller. It retains the mesmerizing textures of an art film, thanks in part to cinematographer Odei Zabaleta’s burnished images. The film’s visual appeal also owes much to Bárbara Enríquez and Alejandro Garcia’s production design, which adds elements not only of character but also of understated social commentary. As Sonia and Villalba go in search of the insurance executives, they climb the social ladder, so to speak, visiting swank clubs and the posh homes of the very rich.

The journey tells you lots about the different levels of wealth in Mexico, even as the story indicts a kind of corruption that keeps many hapless citizens at the mercy of the predatory rich. And that, of course, is tale that could be told almost anywhere in the world today, which is why this beautifully made film will hit home in any country it visits.