Vampires will always be with us, representative as they are of humanity’s endless interest in blood-sucking creatures of the night who stand in the tense space where fear meets desire, and two of the dreamiest most romantic movies released this year have been vampire movies. Jim Jarmusch’s “Only Lovers Left Alive” created a nocturnal dreamspace of love and old (really old) age, and music and survival, with two soul mates meeting up again and again throughout the endless abyss of time. Ana Lily Amirpour’s black-and-white debut feature “A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night,” with a vampire in a chador stalking the denizens of an Iranian town called “Bad City,” owes a lot to Jarmusch, and in many ways the relationship seen between the two lead characters in Amirpour’s film could be seen as the younger incarnations of Adam and Eve in “Only Lovers Left Alive.”

Along with Jarmusch, “A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night” is steeped in other influences: Spaghetti Westerns, 1950s juvenile delinquent movies, gearhead movies, teenage rom-coms, the Iranian new wave. There’s an early 1990s grunge-scene club kids feel to some of it, in stark contrast to the eerie isolation of the nighttime industrial wasteland in which the film takes place. The number of influences here could have made “A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night” yet another movie-mad parody or an arch exercise in style; instead, the film launches itself into a dreamspace of its own that has a unique power and pull. The images are suggestive and symbolic, resonant with intersecting meanings and emotion, nothing too spelled out or underlined. Some of the images sit there unmoving for too long, but that very same stasis also helps create and enforce the underlying tension, the tormented space between people even when they are standing very close together. The film feels extremely personal. It is clear in every frame that Amirpour has put her own dream onscreen.

Filmed in the desert in California, with an excellent Iranian ex-pat cast, “A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night” introduces us to a sprawling yet interconnected cast of characters. They all live in Bad City, an Iranian town filled with bad bad vibes, surrounded by pumping oil drills, seen like galumphing prehistoric beasts, going up and down, up and down. The opening sequence is classic Spaghetti Western (even down to the font of the title credits), mixed with a James Dean-era aesthetic, with a kid in a white T-shirt, blue jeans, and a 1950s pompadour walking around on the blasted-out outskirts of town. He drives a tail-finned Ford Thunderbird, its chrome gleaming in the bright sun, the car carrying so many powerful associations with it, of cool-ness, of Americana, of mobility, of status.

The characters we meet are archetypes, made strange when in service to Amirpour’s unique vision. There is Arash (Arash Marandi), the kid with the vintage car who lives with his heroin-addicted father Hossein (Marshall Manesh). Arash deals drugs, too, as well as taking odd jobs as a gardener on the isolated rich side of town, having a tense flirtation with a rich girl who calls him into her bedroom. Dominic Rains plays the pimp Saeed, with the word “SEX” tattooed on the front of his throat, who supplies Hossein with drugs, steals Arash’s precious car as payment, and harasses and abuses the prostitute (Mozahn Marnò) who works the dangerous streets for him. There is a little boy wearing a ragged coat (Milad Eghbali) who is a witness to everything, an innocent bystander to the corrupt and horrifying events of Bad City going on right before his eyes.

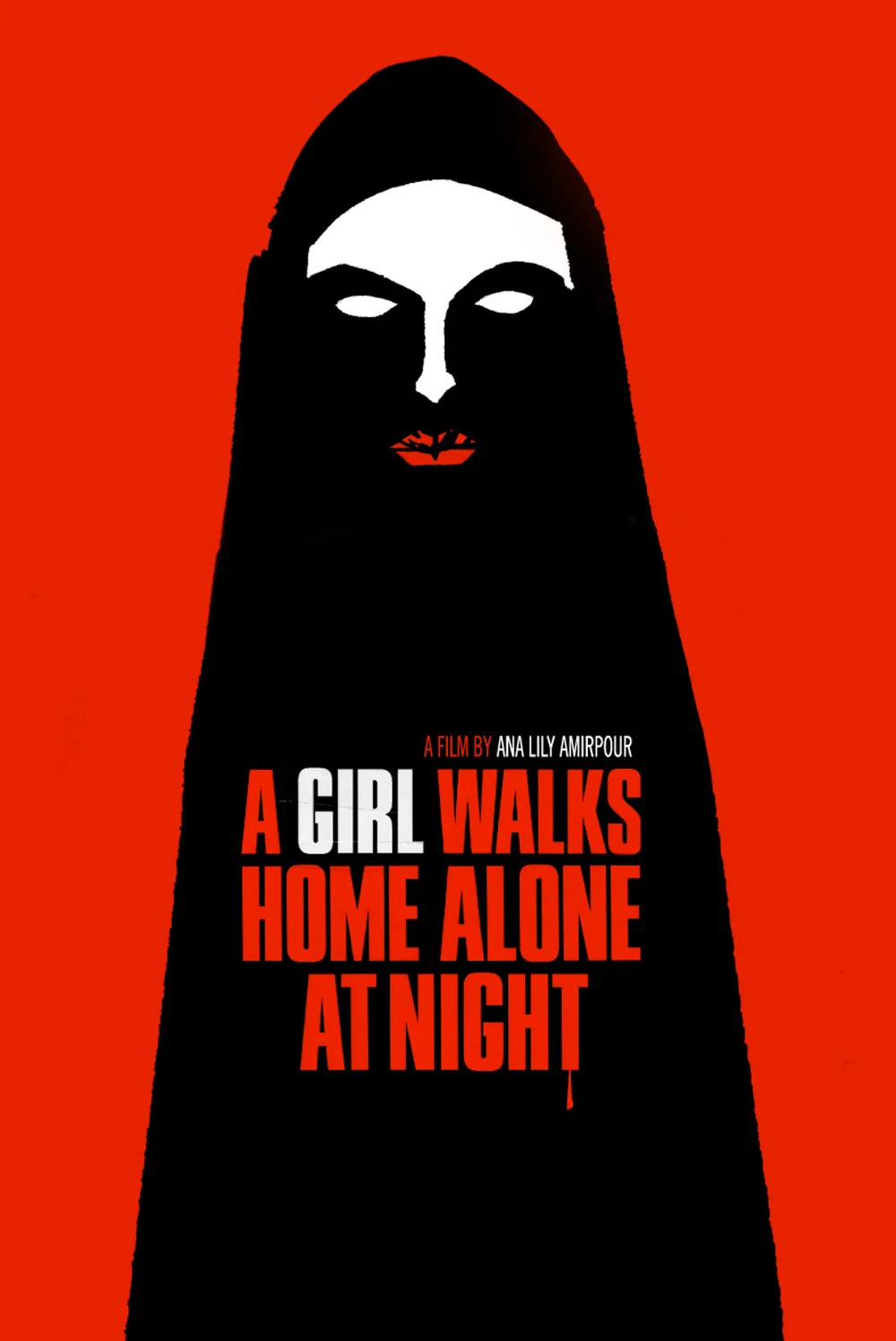

And then there is the vampire, known as Girl (Sheila Vand). The shadows are so pitch-black that she is able to stalk the streets in her full chador practically undetected. She hides almost completely in the liquidy black, revealing herself to her victims from across the wide expanse of vacant lots or abandoned parks. At one point, she skateboards down the middle of an empty dark street, her chador flowing behind her like gigantic black bat wings. The Pimp thinks she might be a prospective streetwalker and invites her back to his place, turning up the techno music, laying out lines of coke on the table. She stands motionless in the background, a shrouded, staring figure. People do not understand what she is or who she is, until it is too late.

Arash, let loose into the night, trying to get his car back from the pimp, trying to meet up with the rich girl at a nightclub, encounters the gliding ghostly figure in a chador a couple of times before they connect. At one point, returning from a costume party (where he went as Dracula), he runs into her on a lonely deserted street. When she sees the drunken Dracula staring up at a lamp-post, mesmerized by the light pouring out into the night, she stops. Does a double-take. Dracula? Is that you?

They have a couple of scenes together, two in particular, one in her basement dwelling place and one out by a power plant, that rank as two of my favorite sequences in any film this year. Both shiver and pulse with unspoken feeling, longing, and an acute and earnest romanticism. The walls of The Girl’s dingy apartment are covered with posters from concerts she has clearly seen in the course of her eternal life: The Bee Gees, Madonna. She listens to records on a turntable. There is a whirling disco ball spinning above, throwing its lights across the grime. In a wordless moment he moves towards her as she stands at the record player, her back to him, the music creating a wall of sound, a wall of feeling. There is a rhapsodic catharsis in a moment like that, the stasis of all that came before suddenly releasing itself in a whoosh of emotion.

Conversely, that same static feeling can sometimes just sit on the screen, the tension within the frame dissipating, the image a beautiful picture but with no further revelations to be had within it. Stasis can make the film sag, on occasion, slacken and lose that taut weird otherworldliness. For the most part, though, Amirpour helms the ship confidently and with a lot of love and care.

Similar to Jarmusch, music is extremely important to Amirpour (who has also worked as a DJ), and the music choices in “A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night” are intuitive and perfectly placed. There are a lot of catchy Iranian pop songs, and a couple of sequences are built explicitly around the song used as underscoring. Amirpour has a great feel for that, merging the events onscreen to the song choice in a way that feels inevitable, in a way that opens up the scene.

Much of the romanticism in “A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night” comes from the visuals (Lyle Vincent shot the film). The cinematography is glamorous black-and-white, crisp and specific, with light from the lamp-posts and car headlights refracting and fuzzing across the screen in a blurry line. The contrast between black and white is high, but there is much spill-over, light cutting through the blackness with difficulty, leaving fragments of itself in a trail behind. There are moments that stand alone, images both familiar (as though seen in a dream or a deja vu), and yet never presented before in just such a way: a black-veiled woman standing on the other side of an empty parking lot, barely perceptible through the gloom, surrounded by nothingness, a figure from a nightmare.

The Girl is a vampire who targets men, specifically men who are mean to women. Because she is in a chador, one can make all kinds of political and social connections with that storytelling device: she is an avenging angel of dominated and scorned womankind. Amirpour lets the images do all of the work for her, a huge strength of the film. The image of a female vampire skateboarding down a street, her voluminous veil flying out behind her, does the job with more poetic satisfaction and truth than any explicit monologue about the repression of women could ever do. At one point, she leans to whisper in the ear of the frightened urchin child, telling him to “be a good boy.” It sounds like a threat. Be a good boy, or else … But these are undercurrents only, the subterranean basement of the film’s psyche. Essentially, “A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night” is a film about film, a fresh and exciting re-imagining of a well-worn oft-told genre.