Being poor in this country is considered a crime, and it always has been. The perceived sin of poverty is supposedly committed by those who are just too shiftless and lazy to “pull themselves up by their bootstraps” and succeed. Never mind that those bootstraps may have been Krazy-Glued to the concrete by institutionalized racism, class warfare and the redlining of neighborhoods; in the jaundiced eye of politicians and the wealthy, we all start from equal footing and the reason we’re not all rich is because we’re just not as motivated. So it’s important that one of the many things filmmaker Ronit Bezalel points out in her insightful documentary “70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green” is that, despite one’s attempts at success, there were forces that strove to tamp down one’s ascendance. Nowhere is this more prevalent than in one’s living arrangements: where a person resides is determined by numerous corruptible factors beyond their control.

The restriction of where a certain type of people could live is what begat Cabrini Green. The famous Chicago housing project was built as a separate area to house the influx of African-Americans migrating from the South. Since space was limited, the city built upward, creating the familiar high-rise structure that many inner-city projects took. Cabrini Green became its own separate entity from the city of Chicago, with its own police force and a sense of community that arose as much out of necessity as it did out of logistics. The narrator describes Cabrini Green as “just one mile from Downtown [Chicago], yet in a whole ‘nother economic dimension.” Its 70 acres, bordered by North Avenue, Halsted Street, Chicago Avenue and Orleans Street, were a piece of real estate worth salivating over, provided it could be reshaped.

“70 Acres” points out that Cabrini Green rose from the ashes of a prior, similarly impoverished neighborhood called “Little Sicily,” a place filled with Italians, Jews and Blacks, none of whom could legally live anywhere else. The city of Chicago uprooted the denizens of Little Sicily in the same way it would uproot Cabrini Green’s inhabitants 60 years later. In both instances, the newer housing came with a different, more stringent set of rules that prohibited many from returning to their old neighborhood. The only difference here is that, while many of the Italian and Jewish people were able to move into the White neighborhoods, their former Black neighbors still could not. Those people went to Cabrini Green, which, as the documentary opens, is being converted to the “mixed income” housing that many displaced residents won’t be able to move into either.

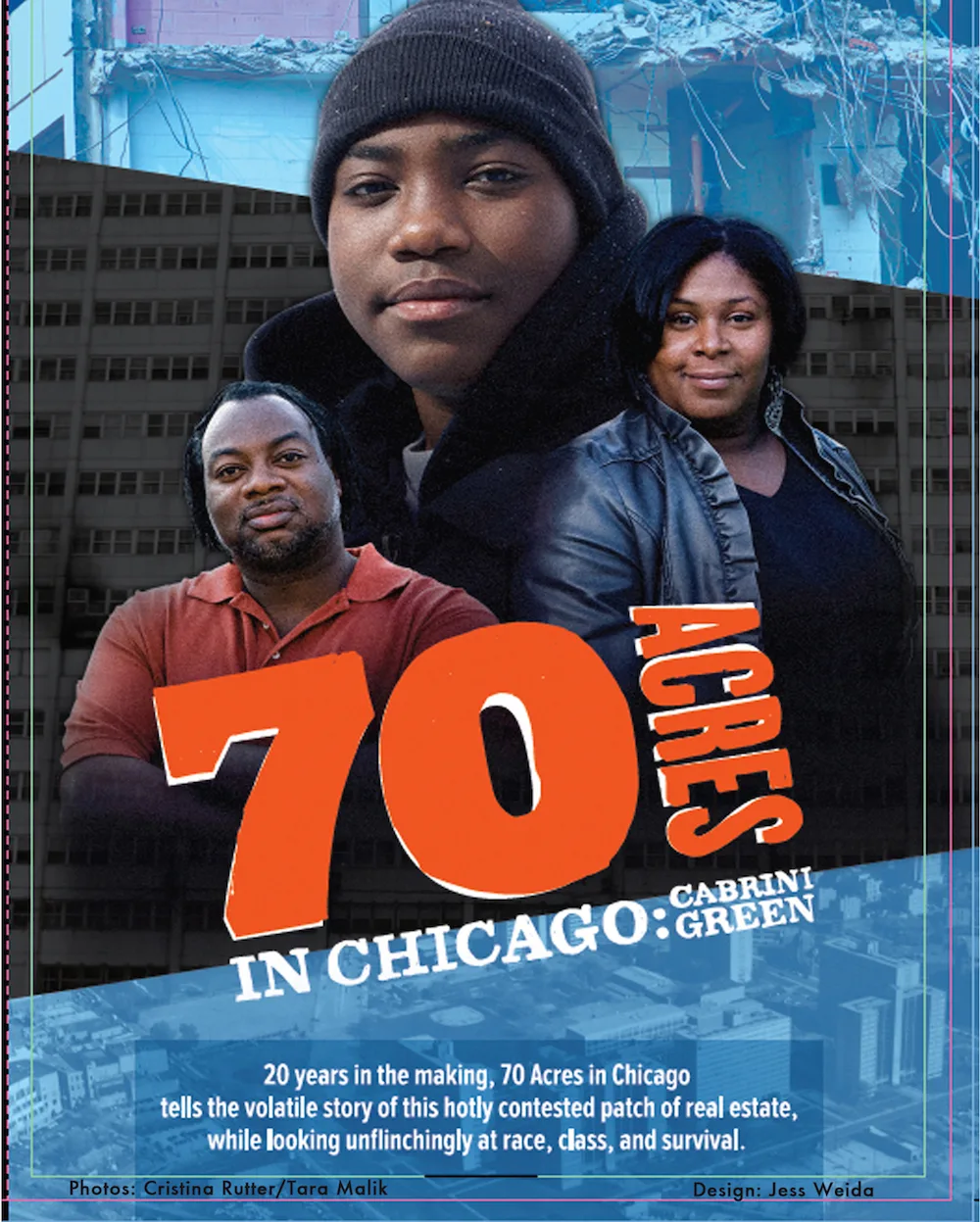

“70 Acres in Chicago: Cabrini Green” continues Bezalel’s 20-year look at Cabrini Green, and one of the film’s strengths is its casual depiction of the passage of time. For example, we meet a teenager named Raymond McDonald who is a little older and wiser every time we check in with him. Raymond’s story is the film in microcosm. He’s present at every step of Cabrini Green’s conversion. At the beginning, we see him and his fellow high school classmates asking Chicago’s Mayor Daley how he would feel about being removed from his own neighborhood. We then see him in a botched interaction with some new White residents of the first section of mixed-income housing (“They don’t want me here,” he says to the camera). Later, we see that his successful dog-training business has become a casualty of the increasingly strict rules of the new houses, rules that affect the lower-income residents far more than their new neighbors. We also follow Mark Pratt and Deirdre Brewster, older residents who as activists speak out about the changes as they occur.

Though the film runs a (too-short) 60 minutes, it speaks volumes about gentrification and the concept of “mixed-income” housing, the latter of which feels like a social experiment slowly going awry. “In theory,” says Mark Joseph, an associate professor of Community Practice, “the most basic thing this is supposed to do is reconnect those living in public housing to the rest of the community.” The results are middling at best. One new neighbor throws block parties that are barely attended by a mix of different income residents, and those who do tend to stay in their own groups. Also, as the film progresses, we notice that those former Cabrini residents lucky enough to transition over have become fearful of the conditions stacked against their favor. Any bad behavior, real or imagined, complained about by the neighbors will result in eviction.

“To live here, you need to be a nun,” one resident says regarding the numerous new rules regarding safety. One of these rules states that if you have any kind of criminal record (even a misdemeanor), you are not allowed to live in the new houses. One woman describes how her 18-year-old daughter, who had been arrested for fighting in school years prior, could not live with the rest of the family. “If you have a record of any kind,” another resident says, “and in Cabrini Green it’s very likely somebody in your family does, you won’t be living in the new Cabrini Green.”

Bezalel does a very good job editing many years of footage together, telling her story through the interactions of politicians, residents and the educators who provide historical context. She stands back, offering no solutions while letting the viewer draw his or her own emotional conclusions. Joy, sorrow and anger exist above and below the surface, but “70 Acres” never forces one’s response. I am sure that my own experiences seeing my hometown undergo a similar transformation teased out a higher level of anger in me than some viewers may feel.

Cabrini Green’s demolition began in 1995 and ended in 2011 with the last tower being demolished. “70 Acres” presents a New Orleans-style funeral for that last building, with a drumline of musicians playing, and former residents coming back from all over the U.S. to attend the send-off. One former resident, who has moved out to the suburbs, tells us that, despite the safer environment he currently inhabits, he is not as comfortable as he was in Cabrini Green. “There was violence,” he says of the projects, “but there was also a sense of community that surrounded you.” This notion of “dealing with the Devil we know” is what a lot of pro-gentrification advocates completely miss. This film connects the current “for your own good” characteristics of today’s gentrification with its prior, more overtly racially motivated and classist incarnations. The elevation of one poor neighborhood forces the ouster of its residents and the creation of another. The cycle continues, and the circle remains unbroken.