Tony has a vacation home in Spain now, with a veranda and a swimming pool. He’s seen some hard times, but at 49, he is basking in contentment. We see him in the pool, tanned, splashing with his family.

When you live with Michael Apted’s “Up” series of documentaries, there tends to be one character who most focuses your attention. For me, in “28 Up” through “42 Up,” it was Neil, the troubled loner. As a boy, he wanted to be a tour bus guide, telling people what to look at. As an adult, he still has an impulse to lead and instruct, but it hasn’t worked out, and he became a morose loner. In one film there was a shot of him standing next to a lake in Scotland, in front of his shabby mobile home, no one else in sight; I thought, “Neil will be dead by the next film.”

It didn’t work out that way, and Neil provides the biggest surprise of “42 Up.” But Tony’s development in some ways may be as fundamental as a transition. What happens to him helps illustrate the importance, even the nobility, of this most extraordinary series of documentaries.

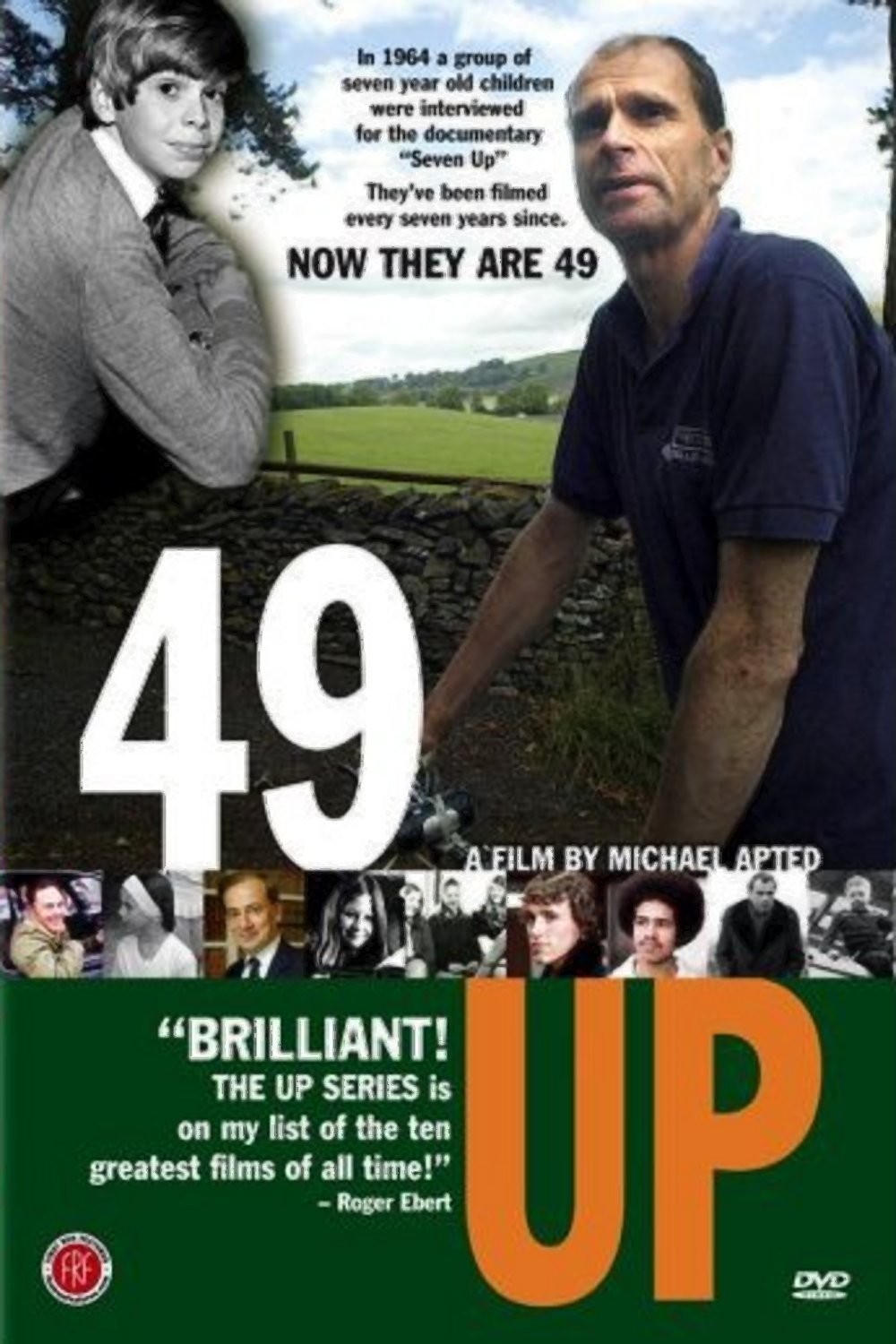

In 1963, Granada Television in Britain commissioned a film about a group of children born in 1956. Drawn mostly from the upper and lower ends of the British class system, they were asked about their plans and dreams. The idea was to revisit them every seven years and see how they were doing. As a plan, this was visionary, even foolhardy, but here we are at “49 Up,” and the children of the 1963 film have children and grandchildren of their own. Anyone who has followed he series develops a curious fascination with their lives, because they are lives. This is not reality TV with its contrivances and absurdities, but a meditation on lifetimes.

Consider Tony. At 7 years old, he wanted to be a racing jockey. Brash, crew-cut, extroverted, he made it all seem clear. He did briefly become a jockey, even racing against the great Lester Piggott, but as an adult he was a London taxi driver.

Apted, the director who has been with the “Up” series from the beginning, was in 1963 a lad who wanted to be a movie director. He grew up to become one. In a sense, he is another of the film’s subjects, growing older off-camera. There was a time when he was convinced that Tony would eventually fall into a life of crime, and so he asked some questions and shot some scenes in anticipation of that development.

Tony did not become a criminal, and Apted learned his lesson, he told me. He decided to never anticipate what might happen to his subjects — to simply revisit them and catch up with their lives. Similarly, he decided to bypass politics; prime ministers and governments come and go during these films, but Apted doesn’t see his subjects as political creatures; whatever their politics, he is concerned more with what is happening in their lives, and how they feel about that.

I am not British, was born 14 years before the subjects, and yet by now identify intensely with them, because some kinds of human experience — teenage, work, marriage, illness are universal. You could make this series in any society. As its installments accumulate in my memory, they cause me to regard the arc of my own life — to ask if I, too, contained at 7 the makings of who I would become.

Certainly between 7 and 14 my path was settled. I wrote for the grade-school newspaper and used a crude “hektograph” machine to write and publish “The Washington Street News.” I was always going to be a journalist, and very old friends who knew me at 12 say, “You haven’t changed.”

Neither has Tony. He has expanded in his ideas of what his life can provide him, but he is still the over-confident, driving, ebullient personality he was at 7. Bruce, who wanted to be a missionary at 7, got involved in inner-city schools that were a contrast to his upper-class background. Neil’s life has contained enormous surprises, but he is always definitely Neil — worried, discontented, fretting that the world is not following his instructions.

You do not have to have seen any of the earlier films to understand this one. George Turner, Apted’s cinematographer since “21” and editor since “28,” provides flashbacks to earlier days in each life. By now that is a daunting editing task, but he is able to do it, and keep us up to speed.

The early films were shot in black and white. Then Apted went to color. Now he is using digital. The subtle visual alterations help to suggest the passage of time. So do grey hairs and potbellies. None of the original group has died, most have prospered and found happiness. And with the passing of every seven years, the more they look different than they were at 7, the more they are the same.

Michael Apted’s “Up” series remains one of the great imaginative leaps in film. I came aboard early in the series and I, too, have grown older along with it. In Tony’s eyes at 7, reflecting in his mind his triumphs as a jockey, I can see the same eyes at 49, gazing upon his swimming pool in Spain. He ran the race, and he won.