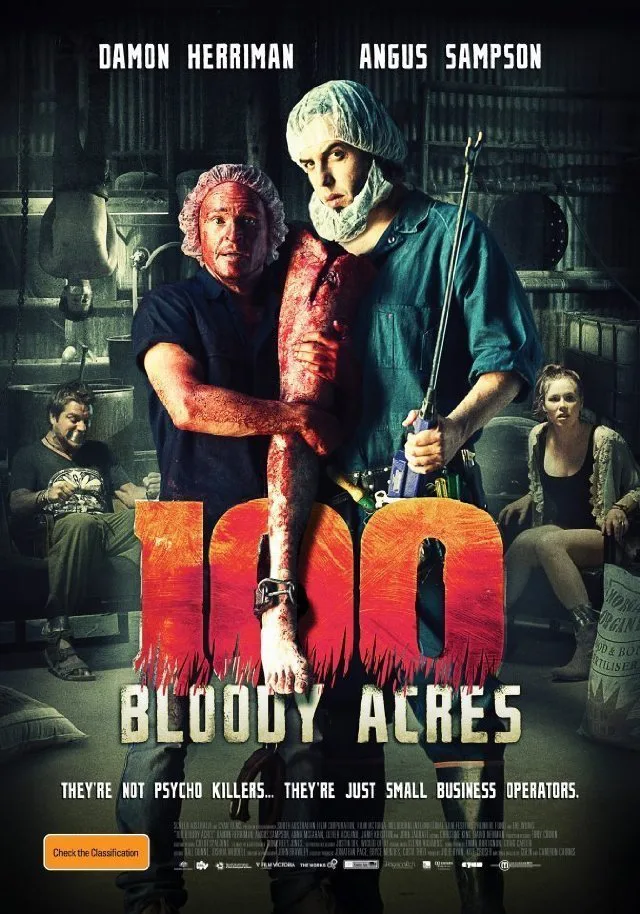

I knew nothing of “100 Bloody Acres,” the debut film by sibling writer-directors Colin and Cameron Cairnes, until I saw it. I certainly didn’t expect it to be the best low-budget horror comedy since “Shaun of the Dead,” and one of the most assured first features in ages. Set in an unspecified part of the Outback, it’s one of those “pampered city folks terrorized in the country” pictures, a genre that encompasses everything from “Deliverance” through the underrated “Wolf Creek.” The heroine is Sophie (Anna McGahan), a country gal passing through familiar territory in the company of two handsome young men. One is James (Oliver Ackland), a polite, responsible fellow who loves Sophie and intends to marry her. Problem is, Sophie’s secretly sleeping with their traveling partner Wes (Jamie Kristian), an oddly likable jerk-stud-fratboy type who likely reminds Sophie of the sort of cocky yet alluring country tough guys she knew back in the day.

James has no idea that Sophie’s stepping out on him, but he’ll find out soon enough, and in the least desirable circumstances. When the trio’s car breaks down, they cross paths with Reg Morgan (Damon Herriman, aka Dewey Crowe on TV’s “Justified”). Reg is half of the Morgan brothers, local businessmen who sell blood and bone-based fertilizer. The Morgans have recently purchased their first-ever set of ads on local radio; Reg is anxious to hear them play so that he can know their success is real. We meet Reg at the start of the film, pulling a car accident victim from a wreck and stashing him in the back of his panel truck along with the other roadkill he’s found.

When he chances upon the stranded trio, he’s inclined to drive on until he spots Sophie. Her beauty and charm would beguile any man, but especially a man who spends most of his waking life trolling back roads for fertilize-able meat and enduring abuse from his older brother Lindsay (Angus Sampson), a bearded hulk who has some of the glowering, bitter hostility that Peter Stormare exuded in “Fargo.” Reg offers the trio a ride, but on the condition that Sophie sit in the cab with him while the men sit in back with all that stinking flesh. They reluctantly agree, and when they discover the dead driver under a pile of feed bags, a pity-ride turns into something darker.

The Cairnes brothers have clearly studied the work of another sibling duo whose last name starts with “C.” But while the film’s mix of over-the-top gore, yokel slapstick, deft wordplay and free-floating ominousness recalls “Blood Simple” and “Fargo,” “100 Bloody Acres” is not a Coen brothers ripoff. Nor is it a laundry list of film school homages, which is no small feat when you consider that the script evokes everything from “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre” and “Last House on the Left” to Akira Kurosawa’s “Stray Dog” and “Yojimbo,” Rob Zombie’s “The Devil's Rejects,” and the exuberant exploitation pictures that Peter Jackson used to make.

Nothing about this film plays out quite as you’d expect. Reg, for instance, initially seems a standard-issue movie yokel, mangling the language and reacting to adversity with wallaby-in-the-headlights terror; but “100 Bloody Acres” eventually reveals his hidden layers. Over the course of the film Reg seems increasingly sympathetic without any special pleading by the script, and without minimizing his culpability in his brother’s viciousness. Herriman’s performance is thoughtful, funny and often touching: at times I felt as though I was watching a young Michael Rooker play Norman Bates as a tragic clown.

All the characters are as well-drawn as Reg. They keep surprising you with artfully-revealed bits of backstory and amusing character touches, such as when Wes offers James a tab of LSD when they’re in the back of the truck, with the no-big-deal affability of one hobo offering a cigarette to another while riding in a boxcar. I love the way Reg blurts out to Sophie that she’s a “city slu—uh—uh, slicker!” when they’re riding together; it clues you in on the fearful misogynist attitudes that Reg learned in isolation with his scary big brother. Even better is Sophie’s reaction to Reg’s gaffe: rather than smack him down, she explains that the fact that she likes sex and feels comfortable having more than one boyfriend doesn’t mean she’s a slut, just that she’s not the settle-down type. (Her attitudes would be no big deal if she were a he.) Sophie assures Reg that deep down she’s still a “country girl,” a phrase that gets redefined away from stereotype the more time you spend in her company. Gender studies buffs are going to have a field day analyzing her choices in this movie, and not disapprovingly.

James and Wes are surprising as well. On first glance they seem like a typical “nice guy”/”bad boy” pairing. But Wes is funnier and more decent than you think, and James isn’t the white knight you assume he is. Maybe Sophie could be satisfied with just one guy if she could combine her two boyfriends, and create a sensitive, loyal, caring man who’s also boisterous and fearless and funny and doesn’t seem as though he has a fishing pole up his bum twenty four-seven.

Lindsay is probably the film’s most straightforward character—a heavy whose violence drives much of the film’s action—but he isn’t one-note either. There’s a sadness in his eyes. Maybe he realized at some point that he’s an ogre, the kind of guy who can string up a hostage by clanking chains over a meat grinder and talk to him calmly as he prepares to gut him; then maybe he decided to not think about it, as real-life ogres do. The throwaway moments—such as Lindsay absentmindedly singing along with a song on the radio as he drives—hint at the humanity he must have lost long ago. He just wants the family business to be secure.

This is a smartly written and acted and exceptionally well-directed movie. Watch, for example, how the Cairnes brothers plant the information that Jim has brought along a ring that he intends to place on Sophie’s finger, then observe what they do with the ring over the course of the picture. Watch what they do with the recurring images of lost fingers and limbs, and how the film pays them off. Appreciate the opening credits sequence, with its wordless shots of signs advertising local businesses. “Just Picked Figs—Thanks For Your Honesty,” one says. “National Trust HBC and Tourists Piss Off,” says another. These signs don’t suggest smug big-city mockery, but firsthand knowledge.

The Cairnes block their actors with the delicacy of stage directors, and use the frame line to hide and then reveal important objects and bits of information. Rather than spend the whole film jamming a wobbly close-up camera into the actors’ tonsils and cutting every three seconds, they shoot them from a variety of distances and hold shots as long as they can before cutting. They aren’t afraid to hang back sometimes; there are a couple of shots from the point-of-view of characters in a field beyond the farmhouse, watching other characters racing speck-like in the distance, that inspire laughs of affirmation because they feel so right. Late in the movie the filmmakers bust out some expressionistic slow-motion, lingering on a moment of realization or transformation as a character marches toward destiny, and it doesn’t feel like a fussy flourish, but an epiphany. And keep an eye out for the final shot: it’s Coens-worthy.

Don’t see this movie if you have a weak stomach, or if you don’t like movies that mix horror-movie violence and cornball humor. Don’t see if it you’re expecting production values beyond a couple of vehicles, a farmhouse and about twelve buckets of gore. Don’t see this movie if your definition of a great or classic film is one that bowls you over with the importance of its subject or the awesome scope of its vision. Do see if it you want to be be reminded that it’s possible to make a relaxed, engrossing, funny, sometimes scary movie on almost no money. And do see it if you want to be able to say you were there when a couple of unknown filmmakers embarked on a long and increasingly impressive career, because something tells me that’s what we’re about to see from these Cairnes fellows. They know what they’re doing. The family business is secure.