I wish I’d written this piece while James Shigeta was still alive; it’s best to appreciate people in the here and now. But a posthumous appreciation will have to suffice. Bottom line: Shigeta, who died yesterday at 81, was a marvelous performer, and his work as Nakatomi Corporation President Joseph Takagi in the original 1988 “Die Hard” is one of my favorite examples of how an imaginative actor can sketch out a life in just a few scenes and lines.

Shigeta was a versatile actor and musical performer. He was born in Honolulu and cut his teeth entertaining his fellow Marines in variety shows during the Korean War. He became a recording star in Japan after the war despite not speaking a word of Japanese, won first place back home in the United States on the 1950 competitive variety series “The Original Amateur Hour,” was marvelous in Samuel Fuller’s 1959 film “The Crimson Kimono,” shared the 1960 Golden Globe for Most Promising Newcomer with George Hamilton, Troy Donahue and Barry Coe, and played Wang Ta in the 1961 film version of “Flower Drum Song.” His speaking voice was a deep tenor with a hint of a quaver, as if he were suppressing the raging emotions he always naturally felt. And his singing voice was sunshine.

Most contemporary audiences, though, knew Shigeta as Takagi, whose death at the start of “Die Hard” jolts both the hero and the viewer into realizing that this is not just an action romp—that every person onscreen, however seemingly minor, had a life before this drama began. A great deal of Takagi’s charisma comes, of course, from Jeb Stuart and Steven E. DeSouza’s script, and from John McTiernan’s direction. No mere shoot ’em up, “Die Hard” is a rare gun-crazy action extravaganza that takes the trouble to define its characters with fine brushstrokes as well as broad ones. It’s unusually adept at finding ways to make exposition dynamic, so that the actors can relax and dig into moments instead of trying to liven them up.

My favorite example is the scene right after Hans Gruber (Alan Rickman) and his terrorists have stormed the Christmas Eve employee party and are trying to figure out which of the party guests is Takagi, who holds the codes that can unlock the company’s vault full of art treasures and bearer bonds. Hans glides imperiously around the room reciting Takagi’s (presumably official) biography. He was born in Japan, his family was interned in the US during World War II, he attended the University of Southern California on scholarship, and so forth. “Law degree, Stanford, 1962,” Hans intones. “MBA, Harvard, 1970. President, Nakatomi Trading. Vice-chairman, Nakatomi Investment Group.” Finally Takagi, who’s been restrained somewhat by his right-hand woman (and the hero’s estranged wife) Holly Gennero (Bonnie Bedelia), says, “Enough.” “And father…of five,” Hans finishes, his smirk morphing into a death’s-head sneer.

The reaction shot of Takagi makes the moment. Takagi is rattled but does not appear scared. In fact he seems…angry. The moral outrage in his gaze turns this confrontation into more than a pissing match. It’s as if Takagi is offended not just by Hans’ actions, but by the very existence of people like Hans. (You get a similar chill of undisguised disapproval in the elevator scene, when Hans correctly identifies his suit as the product of “John Phillips, London…I hear Arafat buys his there.” Takagi doesn’t play it cool here; for a brief second he glares at his captor with contempt.) The second revised shooting script for “Die Hard” treats the “resume” scene differently. When Hans comes in and starts making his insinuating remarks, the description reads, “Takagi is shoved forward”—i.e. given up by the crowd, I suppose. But it adds, “He is worried but far from cowed.” Those last five words sum up Shigeta’s demeanor throughout the brief period where he’s terrorized by Hans and his gunmen.

Shigeta is credible as the leader of an international corporation because he has the demeanor of a man who’s comfortable wielding power. His gentle smile and twinkling eyes affirm that he’s also a good man—the kind of boss that you like and respect. Something in Shigeta’s warm screen presence suggests that Takagi may, in fact, be that rare leader who gets people to do what he needs them to do while somehow making it believe it was their idea. He gives you the sense that this construct who is essentially cannon fodder, the first casualty of the terrorists, is a fascinating person who has suffered, endured and transcended. You can imagine Takagi at 30, at 20, as a kid even.

There are several layers of awareness in how Shigeta-as-Takagi tells Bruce Willis’s John McClane, “Pearl Harbor didn’t work out, so we got you with tape decks”; it’s a laugh line that wins McClane over at that precise moment, but Shigeta delivers it in a slightly rehearsed way, as if he’s used it before (and as a Japanese-American in the Japanophobic ’80s America, he almost certainly did) and is a bit tired of trotting it out even though, old pro that he is, Takagi never fails to sell it. These are all examples of an actor giving a character more than was likely there on the page—fleshing the person out, putting meat on the bones, as it were, through expressions, gestures, choices.

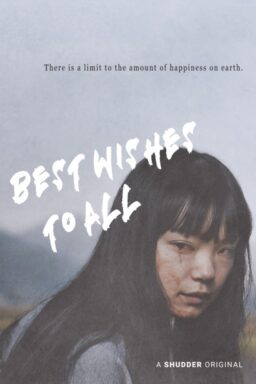

My favorite moment in Shigeta’s performance occurs during Takagi’s last minutes of life. Hans wants the codes to the vault. Takagi won’t give them away and in fact warns Hans, correctly, that it’s a complex security system, not dependent on any one person’s access. Hans again compliments Takagi on his suit and says it would be a pity “to spoil it.” The movie cuts to a reaction shot of Takagi. Shigeta’s face—captured in the screenshot at the top of this piece—is one of the best single illustrations I’ve seen of the notion that people who have recognized that they’re about to die can steal back a bit of dignity by summoning their courage and refusing to be cowed.

Look closely at Shigeta’s eyes in that scene; they shimmer for a fleeting instant, as if showcasing an actual spark of life. “Get on the jet to Tokyo to ask the chairman, I’m telling you, you’re just going to have to kill me,” he tells Hans. He’s not groveling. He’s grinning, as if trying not to crack up. This is a taunt. Takagi dies like a leader. He dies with honor, and his death is not just a plot point, because the filmmakers and the actor made you feel that Takagi stood for something.