Revised 11/17/08

Back in the 1960s, I used to get these long, thoughtful letters from a woman named Elaine Madsen, who lived on the Southwest Side and was married to a Chicago fireman and was raising three kids. She was a movie fan and she wanted to be a writer. One letter asked me what I thought about letting her kids see “Night of the Living Dead.” Michael was about 9, and Virginia was five years younger. I wrote back that I thought it was a bad idea.

“But I sneaked out and saw it anyway,” Michael Madsen confessed.

“When you were 9?” Elaine said.

“Yeah. You were right. I shouldn’t have seen it.”

“I went and saw ‘Torso,’ which was another movie you banned,” Virginia told her mother. “Now every time I drive down Lake Shore Drive and see that big electric sign for Torco, I get reminded and I feel guilty.”

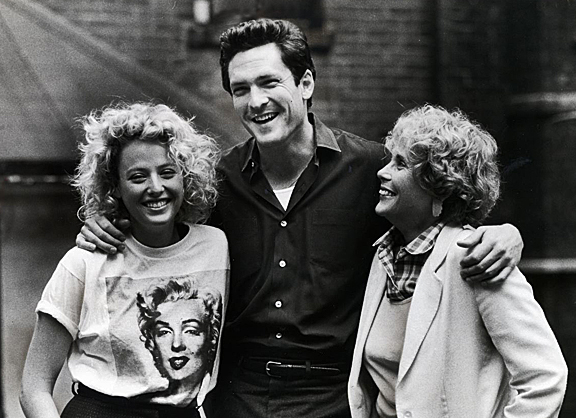

Virginia and Michael were home for the weekend, having lunch with their mom. Things have turned out well for them. Both of them are movie stars, and Elaine is a writer and a filmmaker, just like she planned; a couple of years ago, she won an Emmy.

This is kind of an amazing story.

It begins when Elaine decides in her 30s to go to college, and it continues when she breaks the news to her kids that she is getting divorced and there isn’t going to be much money anymore, and they are going to live in a cheap apartment in Evanston because their mother has this crazy dream. [She also, she told me in 2008, wanted them to grow up in a neighborhood that wasn’t all-white.]

“I said it was my turn, now,” Elaine recalled. “The kids could have been awful about it. But they were wonderful. Virginia got a job as a waitress at P.S. Chicago [a Division Street bar]. Mike was pumping gas, working maintenance. I quit my job because you can’t work 9 to 5 and be a free-lance writer.”

We were sitting on the outside terrace of the apartment where Elaine lives now, in one of those strange old hand-made Sol Kogan buildings tucked into a cul-de-sac of Old Town. It had 2 1/2 rooms on two levels, jammed with books, paintings, scripts, photos and her Macinosh. It had rained earlier, and now the air was fresh and we were passing around the chicken salad. It could have been any two kids visiting their mom, except that in the past few years these two kids have had remarkable success in Hollywood.

Virginia Madsen is a beautiful blonde with a sunny smile whose credits already include two movie leads (“Electric Dreams” and “Creator“) and two important TV roles: co-starring with George C. Scott in “Mussolini,” and Robert Mitchum in “The Hearst-Davies Affair,” where she played Marian Davies. [Since then she has worked in 74 movie and TV roles, won an Oscar nomination for “Sideways” in 2006, and played the angel of death in Robert Altman’s final film, “A Prairie Home Companion.”]

Michael is dark-haired, handsome, rugged. After talking his way into classes at the Steppenwolf Theater Company he had featured roles in “WarGames,” “The Natural” (where he wiped himself out against the outfield wall) and “Racing With the Moon.” He also starred in the ABC-TV series “Family Honor.” [Since then, he has appeared in 150 movie and TV roles, became a Quentin Tarantino favorite in “Reservoir Dogs” and “Kill Bill,” and published his collected poetry.]

Elaine, who recently decided she’d had enough of gray hair and went back to blond, is a sexy, bubbly woman whose documentary about the Chicago film industry, “Better Than it Has to Be,” won an Emmy. She writes for several local magazines, is the film critic for Nit & Wit, and has some screenplays making the rounds.

A few years ago, all of this was only a dream.

“Things sort of started in 1965, when I saw some foreign films for the first time,” Elaine said. “I saw `Woman in the Dunes,’ that Japanese film about the woman who traps the man in the sand pit, and I thought it was stunning that you could tell a story in that way. It really affected me. I began to think I might be able to work in the arts somehow.”

She went to college and started taking writing classes. She began to grow out of traditional roles.

“Today she’s like a different person,” Michael said. “When we were all together as a family, Mom was a mother, a homemaker. She was the one person who gave me the idea that I was going to do something for myself. I didn’t get too much support otherwise. After our parents got divorced and she went on her own, she turned into a different person, she explored all the things she wanted to do, and she taught us to be independent. She took a lot of chances with her life.”

“I raised them,” Elaine said, “with the idea that they should always live their lives out of step.”

“And did you?” I asked them.

“Boy, she sure inspired us,” Virginia said. “We were the class freaks when we were growing up.”

“My sixth grade teacher said we had a problem in the class,” Michael said, “and the problem was me.”

“When I went to New Trier,” Virginia said, “I threw a party because I thought it would make me popular if all the popular kids came. They all accepted. But none of them even planned to come. They didn’t even have the guts to tell me. I had candles, I had bowls of dip, I had the stereo on, and at 10:30 it dawned on me that nobody was coming. So to save face I called them up and told them it was canceled.”

You weren’t popular in high school?

“I didn’t even have a prom date.”

And yet the critics have called you one of the great beauties of Hollywood?

“I always got that stuff. When I was little, people would stare at me and talk about how beautiful I was, and I asked my mother what was going on, and she said it was because I was pretty, and there was a reason for that, but we didn’t know what the reason was. In high school, I was enrolled in the Center for Self-Directed Learning, which was where all the weirdos were, and I was a member of the bun-and-braid brigade. I tore my T-shirts and wore shirts that were too large and I had a big mouth and I was not preppy. I was pretty unpopular.”

Michael was not a raving success, either. “I was pumping gas, running around on a motorcycle, working as a pipefitter, doing maintenance at the Sheraton Oak Brook, an orderly at Skokie Valley Hospital. Nothing was happening.”

He had gone inside to find an album of family photographers, and now he paused at a black and white shot of a totally wrecked automobile.

“This was one of my low points,” he said. “The old Road Runner. I rolled it. I don’t know why nobody was killed. I wrote a poem about it .

Road Runner . . . your color was black

and your feeling was power.

When I’d drive by the high school,

Other hot rods would cower . . .

[so maybe he was born to star in “Hell Ride“]

“So anyway,” he said, “Virginia had always wanted to be an actor, but I got the idea a little later. I went to Steppenwolf to see ‘Of Mice and Men,’ and John Malkovich was playing Lenny, and I was just totally taken into it. Afterwards, I went backstage, and Malkovich was changing out of Lenny and back into himself. I remember he was taking about 10 Dr. Scholl’s foot pads out of his boots. I told him, ‘I want to come here, study here, be a part of this place.’ He said, ‘Why don’t you?’ I said I didn’t have a whole lot of money, I was working in a gas station. He said not to worry about the money. Later, I thought, jeez, he talks to a lot of people, he’s forgotten he even met me. But I got a flier through the mail, and John had written a note on it: I could defer payments. I did, and that was my start. I was swept up there, and my whole life was changed.”

His first film was made in Chicago, and was a 16mm drama named “Against All Hope,” about alcoholism. When Barry Levinson’s movie “Diner” was turned into a CBS-TV pilot, he played the Mickey Rourke role. That got Levinson’s attention, and he gave him one of the better supporting roles in “The Natural.” Then came other supporting work and the 12-week run in ABC’s `Family Honor.”

Virginia, meanwhile, was still bringing people their drinks at P.S. Chicago.

“I told them they should stay in Chicago until they got cast in something, and then they could move to Los Angeles if that’s what they wanted,” Elaine said.

“They were shooting the movie ‘Class‘ on Division Street,” Virginia said, “and I tried out to be an extra and got a small role as one of the girls at the school. One night I was down the street acting in a scene and I saw my manager from P.S., and I asked her if she was an extra, too, and she said, no, but wasn’t I supposed to be working as a waitress right then?”

After “Class,” Virginia followed her brother to Los Angeles. They were both managed by Harrise Davidson, a Chicagoan also active in Hollywood, and within months Virginia was getting big roles, including the lead in “Electric Dreams” (1985), a movie about a computer that falls in love with a cello player. You may also remember her as the hapless princess who appeared out of a cosmic swirl in “Dune” and tried to explain the plot.

“When she was little,” Elaine said, “she would come home after a movie and tell me the entire story and every word of the dialogue.”

“I remember you were mad because I ruined ‘Carrie‘ for you,’ Virginia said.

“Look at this,” Michael said, still turning the pages of the family album. “My senior prom date. I wish I could find her now. Out in Hollywood, all these little starlets running around, they don’t interest me. I come from Chicago, my dad’s a fireman, I want a traditional marriage and lots of kids.” [He has five: Two with his first wife Jeannine Bisignano, and three by his second wife De Anna Morgan, who he married in 1996.]

Did your dad support your acting?

“He’s great now,” Michael said. “Here’s his picture. His name is Calvin. It took him a while. A lot of people would have a problem of parents not understanding when you say you want to be an actor instead of a fireman or a policeman–the jobs he wanted me to aim for. Then you can make a choice. Not have them be a part of your life, or take the time, until they understand what you’re doing. Now he’s proud of us.”

“Even after we were divorced,” Elaine said, “we agreed no third person was gonna tell us what to do with our kids. We’re still a family unit on all the holidays. I have an older daughter with three children–she’s sort of the center of the family now; she’s where we go for holidays.”

“Everything was a holiday when we were growing up,” Virginia said. “Mom was always into production numbers. Valentine’s Day, St. Patrick’s Day, you’d get up for breakfast, everything would be all decorated.”

“Life should be a special occasion,” Elaine said.

“We put on a lot of theatricals around the house,” Michael said. “Puppet shows, little skits, magic shows. We did an act where I put Virginia into the clothes hamper and then pretended to skewer her with swords.”

Fake swords? I said.

“A real sword,” their mother said. “I got it for them at a rummage sale.”

Elaine’s web site is here. http://www.elainemadsen.com/