In the fall of 1989, the Toronto International Film festival programmed a major retrospective of post-war Polish cinema. The North American premiere of Krzysztof Kieślowski’s magisterial “The Decalogue” (or “Dekalog”), his extraordinary series of 10 one-hour films loosely inspired by the Ten Commandments, was the survey’s centerpiece.

Financed by Polish television, the intensely ambitious work took more than three years of writing, shooting and post-production. Having detonated consciousness in the West with “Camera Buff,” “Blind Chance” and “No End,” Kieślowski was now at the height of his artistic powers. The series moved from tragedy to freewheeling black comedy, examining with beauty, tension and grace the interior lives and quotidian details of the residents of a Warsaw housing complex.

He wrote the films with Krzysztof Piesiewicz, a human rights lawyer who originally broached the idea. Kieślowski also used nine different cinematographers, often working in highly varied and different visual textures. “Dekalog” was a showcase for the depth and range of Poland’s greatest actors like Boguslaw Linda, Krystyna Janda, Olgierd Łukaszewicz, Daniel Olbrychski, Grażyna Szapołowska, Jerzy Stuhr and Zbigniew Zamachowski.

The sequencing of the parts did not necessarily correspond to the order of the Commandments. Each part was self-contained and the films could be viewed in any order. The movies are entwined, in other ways, by theme or mood. A significant number of the stories are about the relationships of parents and children. The protagonist of one episode is likely to turn up as a bystander elsewhere.

Stanley Kubrick was an admirer. He wrote a brief foreword to the published scripts, saying about Kieslowski and Piesiewicz: “They have the very rare ability to dramatize their ideas rather than just talking about them. By making their points through the dramatic action of the story they gain the added power of allowing the audience to discover what’s really going on.”

Kieślowski was not a moralist or particularly religious (“I leave that to the priests,” he said in Toronto). He was a dark and somber ironist whose stories of fate, chance, love and vulnerability achieved a depth of expression and emotional intensity that was unforgettable. The works were obliquely political—the ethical and moral conundrums the characters experience feel very connected to the director’s remarkable documentaries—and touched on the tense social and political tumult occasioned by the first Polish-born pope, Jean Paul II, the Solidarity trade union movement, the imposition of martial law and the collapse of communism.

Two months after the Toronto premiere, the Berlin Wall fell. In the interim, Kieślowski made what turned out to be his final visit to Chicago, the city with the largest Polish émigré population in the world. The state-supported system was now in disarray. Talking about the rapid changes, Kieślowski said: “It used to be we had money and no freedom. Now, we have freedom and no money.”

“Dekalog” was rightly judged a masterpiece by those fortunate to see it on the festival circuit that fall. In a cruel twist, the film would remain out of view in North America for much of the next decade because of a complicated Cold War-era rights deal. Kieślowski used the cachet to enter into a new arrangement with the French producer and exhibitor Marin Karmitz for his next four features: “The Double Life of Veronique” and his “Three Colors: Blue,” “Three Colors: White” and his final film, “Three Colors: Red.” Kieślowski passed away on March 13, 1996.

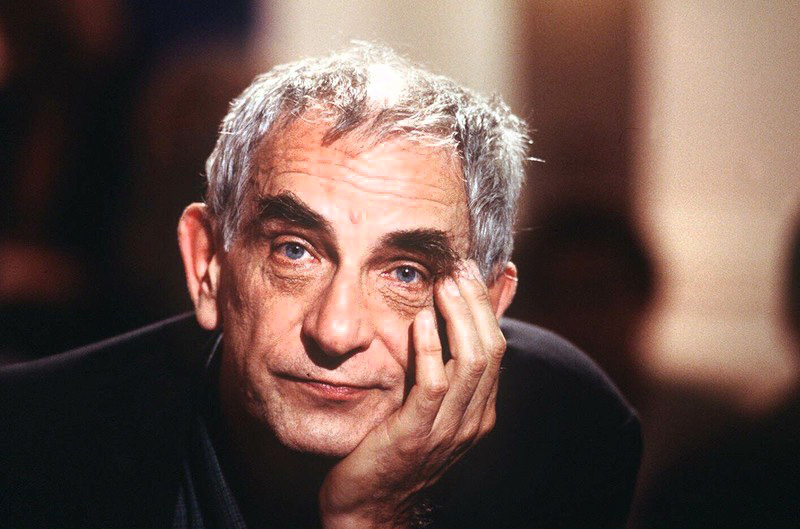

I met and interviewed Kieślowski the first time in Toronto. With his closely cropped hair and the way he often perched his large glasses above his forehead, he could be an intensely forbidding man. On that first interview, I thought he was a bit opaque. My friend and colleague Zbigniew Banas, a Polish-born Chicago critic and writer, moderated and translated the Toronto press conference. Through him, I got to know Kieślowski a little better. Over time he struck me as alternately witty, colorful, relaxed, charming, closed off and intense.

On the 20th anniversary of the director’s death, “Dekalog” returns in a beautiful and exquisite 4K restoration undertaken by Janus Films. The movie opens in New York and Chicago this weekend and in Los Angeles on September 9. Criterion is issuing the film on Blu-ray on September 27.

Criterion previously published high-definition versions of the director’s French language films. In addition to “Blind Chance” (also out on Blu-ray), the Criterion streaming channel on Hulu has made available the director’s Polish-language features, “The Scar,” “Camera Buff,” “No End,” and the two expanded versions of episodes five and six of “Dekalog”: “A Short Film about Killing” and “A Short Film about Love.”

The following interview, appearing in its entirety in English for the first time, is culled from a series of interviews with the filmmaker dating from September 1989 to November 1994, done either individually by Zbigniew Banas, myself or the two of us in collaboration. They were done in Cannes, Toronto and Chicago.

—Patrick Z. McGavin

With the structure of “Dekalog,” was there a more concrete search for order and meaning?

I don’t know. There are also a lot of accidental events, because I believe in chance as a certain cause or force. I’m not a fatalist, but I know a lot of people whose lives are ruled by chance, including mine.

Do you believe the ten films amount to a whole?

That’s difficult to say. There is a certain completion. That’s how it was conceived, but the real test is how it will form in people’s minds and hearts. My opinion here is irrelevant.

In eight of the ten episodes, there’s a mysterious figure (played by the actor Artur Barciś) who observes the principal characters. What is his relationship to the structure?

“Dekalog” isn’t a true series but a cycle of films with different stories. What this character allows is the opportunity to introduce the kind of presence that remind people they are seeing the same thing. All of the protagonists live in the same area; they keep meeting each other. This figure comes and looks for a while, always during the most dramatic moments. He looks and goes away, never saying anything.

The actor would ask me many times. “Who am I? What kind of character should I be playing?” I never really responded. I know there are some people like him, who look at us and never say anything. I think he is one of those people.

In conceiving and writing the stories, were you trying to find some equilibrium between optimistic and pessimistic scenarios?

That wasn’t how I approached it. I always tried to create the ending in such a way [that] the protagonists, once the film ended, they were smarter, knew more, understood something or more human toward one another. I get the feeling that the fact we are so apathetic to one another is the fundamental problem toward the end of the 20th century.

As a filmmaker, is it difficult reconciling your need to create art against the economic conditions of making films?

I need a reason to make a film. The very fact I might have the money or the opportunity isn’t a good enough reason. There has to be a true inner force. There has to be something I would consider important. At the moment [September 1989] I’m completely empty and have to recharge myself.

Your films have dealt exclusively with the social and cultural rhythms of Polish life. Would they be dramatically different if they were about the French or Germans?

That’s difficult to say. Poland is a terrible country. I’m amazed we are able to withstand it. I have a fairly comfortable life because I’m able to travel around the world. For the reason we have real problems, we don’t search for imagined ones. Poland is a country of suffering people whose lives are very difficult. That in turn is very inspiring. The extremity of our daily life makes everyone so incredibly nervous. We are aching so much, like a person who fell from a set of stairs and everything hurts him.

Every day we fall from thousands of steps and everything is extremely complex. We always face humiliation. We always feel we live in a country badly ruled and not as we would like. Consequently, we are sensitive to every other type of pain. It’s a little like tearing off the outer layer of skin. Every kind of touch is painful, even if it’s a loving one.

In your case, are you searching out for something other than what our reality allows us?

That’s certainly what it is. But the search is very futile, the kind where you wave your arms and nobody knows where he is going. This is a blind search, only without the white canes. Not only don’t we know the directions which to move, we don’t know which obstacles stand in front of us.

The story of “The Double Life of Veronique” echoes parts of “Blind Chance,” “No End,”and one episode of “Dekalog.”

Above all this was a film about the possibility of learning, however subconsciously, from the experience of others. There’s not really much chance in this film. Of course humanity as such never learns anything from the mistakes it makes, but it’s very different from one single person.

You used nine different cinematographers on “Dekalog.” You used a different cinematographer for each of the “Three Colors.” How do you arrive at a specific visual texture or style?

It depends on the subject. The story of “A Short Film about Killing” was very crude, so it demanded a very similar approach. “The Double Life of Veronique” is very poetic, so that’s how I decided on the style. The basic visual ideas are written between the lines, and the intelligent cameraman will understand that.

In “The Double Life of Veronique” and the “Three Colors” trilogy, there is a profound sense of displacement, or the artist in exile. Does this figure into your own estrangement from Poland?

I’m a Pole. I live in Warsaw. I have no questions about who I am. (Krzysztof Piesiewicz and I) wrote the screenplays for those [four] films one after the other. We had the concepts of each one in mind when we sat down. We used individual stories to examine how the ideas functioned in everyday life. These ideas concern everybody. They don’t have anything to do with me or where I come from.

How would you characterize your work with actors? Your direction of women seems especially sensitive, creating an extraordinary bond between director and performer.

I try to give them all a sense of freedom, and let them feel that they bring more to the film than their craft. They used their life experiences, and I gain from them. I love them with all of their virtues and faults, and all of their hysteria. We simply sit down for days and weeks and simply chat. With female characters the biggest problem for me is to finding the right actress beforehand. If I can find the right actress then I’m sure she can find the right means for what she wants to say.

How do you see your role as a filmmaker?

To look, to very carefully observe and register how those thoughts and ideas impact the culture and people around you.

How would you assess the state of international cinema?

I believe that we have a crisis in world cinema. This is a crisis of culture. In cinema a certain era has ended and we are already awaiting a new one. Something has to change. All the signs point toward an end of a century, which is usually connected to a notable crisis in the area of culture. The era of saying everything in a straightforward way has ended.

Why did you decide that “Three Colors: Red” would be your final film?

I don’t know what else I could do. I’ve made all of these films, and I’m left with the feeling I’m constantly making the same film. Since 1987, I’ve made fourteen films. I’ve done more than my share. Now it’s time to let others show what they can do.