Here is a film about a feeling. Like all feelings, it is one that can hardly be described in words, although it can be evoked in art. It is the feeling that we are not alone, because there is more than one of us. We are connected at a level far, far beneath thought. We have no understanding of this. It is simply a feeling that we have.

There are theories about events affecting other events at a distance. Chimpanzees on one island are taught a skill, and those on another develop it. Twins say they intuit each other’s feelings. The first four-minute mile is run, and then it becomes common. Two vibrating strings on a quantum level seem to be in synchronicity — or are they in two places at once? Krzysztof Kieslowski‘s “The Double Life of Veronique” (1991) does us the favor of not supplying any explanation for itself, and is not even very clear about what actually happens. It evokes.

It does this above all with the face of Irene Jacob, who plays a Polish woman named Veronica, and a French woman named Veronique. Bergman said the human face is the great subject of the cinema. Kieslowski’s camera spends a great deal of time regarding Jacob’s face. Let’s not waste any time observing how beautiful she is. What he is searching for is her soul. Sometimes he asks her to smile, or look pensive or thoughtful, but sometimes he simply shows her thinking. She shows herself vulnerable, romantic, joyous, tender. She has a good face. We become invested in her introspection.

The film opens in Poland with a luminous and happy young woman who goes to Krakow to visit her aunt. While there, her pure, flawless voice wins the attention of a choir director, whose husband is a famous conductor, and Veronica is chosen to sing at a concert. Before that takes place, she is in a square and sees — herself — boarding a bus. She stands transfixed. The other woman, taking snapshots, doesn’t see her. The Polish Veronica seems to exist on a plane above the mundane; a flasher exposes himself to her, and she hardly seems to notice, or care.

In Paris, we meet Veronique, a schoolteacher. Attending a marionette performance with her students, she sees the puppeteer in a mirror at the side, and he sees her. “Papa, I am in love,” she tells her father. A little later, her father asks her if she is sad. She is, but doesn’t know why. We think we know: A shiver in the web of time and space has vibrated from Poland. She and the puppeteer Alexandre (Philippe Volter) are somehow connected; he pursues her with mysterious gifts and tape recordings. She finds him, flees him, is pursued, and love is admitted. Later, she tells him that all her life she has felt she is in two places at once.

We know how that feels. We feel it ourselves. Let us agree you have a favorite cafe in Venice, where you like to sit alone with a book and a cup of coffee. You have never been to Venice, but set that aside: You are there now. You lift your eyes from the book and are filled with a faint feeling of being still at home. You, at home, occupy the table in Venice. In either place, you are in communion with the other.

Alexandre makes two marionettes that look like her. He tells their story. When one was very young, she touched a hot stove. A few days later, the other knew not to. Yes, and why did the Paris Veronique suddenly stop taking music lessons? A Hollywood movie would tell you, and you wouldn’t want to know. Kieslowski is more delicate. He doesn’t want to know why such things happen, or even if they happen. He wants us to acknowledge we all know how they feel.

Have I made “The Double Life of Veronique” sound as if nothing much happens? The movie has a hypnotic effect. We are drawn into the character, not kept at arm’s length with a plot. Both women are good and true and do nothing shameful. There is a shot of Jacob, who pauses for a moment and lifts her head to the sun, and we know what she is experiencing: Here I am, my life around me, my hopes high, my trust confident, standing stock still, the sun on my face, living in this moment. It is a holy moment.

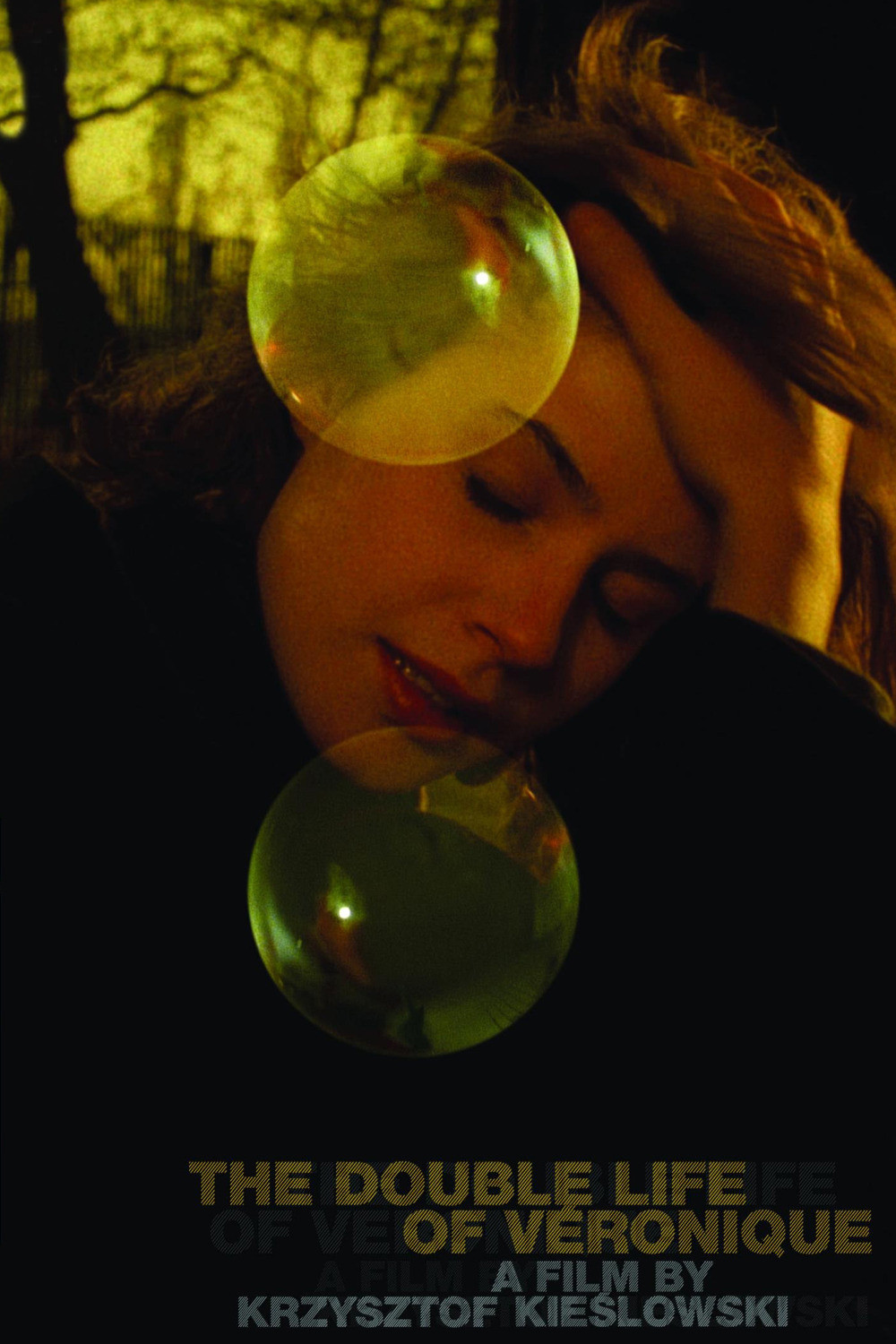

This is one of the most beautiful films I’ve seen. The cinematographer, Slawomir Idziak, finds a glow in Irene Jacob’s pre-Raphaelite beauty. He uses a rich palette, including insistent reds and greens that don’t “stand” for anything but have the effect of underlining the other colors. The other color, blending with both, is golden yellow, and then there are the skin tones. Jacob, who was 24 when the film was made, has a flawless complexion that the camera lingers near to. Her face is a template waiting for experience to be added. She is open to the murmurs of the aether.

The film has some older characters: two fathers, an aunt, the conductor and his wife, a music teacher. These people regard her with wisdom and love. There are no bad people, except the flasher, who shrivels from insignificance. There are also some mysterious people. Who is that woman in the floppy black hat who turns and looks intently at Veronique? I thought for a moment it was Veronica’s aunt, but no. Has she seen her somewhere before? We will never know. And do the aunt in Poland and the father in France resemble each other a little, or is it only in attitude? And, don’t smile, what does the shoestring in France represent? The one so important it must be sought in the Dumpster?

Krzysztof Kieslowski (1941-1996) was a great man. With his writing partner, Krzysztof Piesiewicz, he made films that dealt with spiritual challenges and the uncoiling of fate. His “Decalogue,” released as 10 films of 55 minutes each, deals with people who know what they want to do but not what they should do. Each film centers somehow on a Commandment. Then he made the “Three Colors” trilogy, “Red,” “White” and “Blue,” of which the first, also starring Irene Jacob, is the first among equals. Then he retired at 53 in 1994, and two years later, he was dead.

He is drawn to coincidence and synchronicity. He is little interested in focusing on a character hurtling from point A in the first act to Point C in the third. He is fascinated by Point B, and the unseen threads linking it to past and present. His films can be mystical experiences. He trusts us to follow him, to sense his purpose, to leave the theater having shared his openness to a moment. The last thing you want to do after a Kieslowski film is “unravel” the plot. It can’t be done. If you try it, you will turn clouds into rain. If there seem to be inconsistencies, it is because life and time itself sometimes try again and take an unexpected turn.

Let me give you an example. The Criterion Collection’s two-volume DVD edition, a stunning transfer with a wealth of bonus features, includes as an option the “American ending.” We learn that Harvey Weinstein, the film’s U.S. distributor, felt unsatisfied with the director’s close. He changed nothing earlier but edited in four additional shots, now the last ones in the film. They explain nothing and add nothing. All they demonstrate is that Weinstein thought Kieslowski’s final image, of Veronique’s hand touching the rough old bark of a tree, could be improved by her running across a lawn to hug her father. This whole film is a hug, the kind you share with a very good friend when you are in sympathy about something that is very important.

“The Decalogue” and the “Three Colors” trilogy are also in the Great Movies collection.