O ver a period of five days I interviewed Jodie Foster twice about her new film “Nell.” The first time, in New York, was for television, and she supplied the smooth sound bites she’d been performing all morning for dozens of visiting interviewers. The second time, in Chicago, was for print, and we talked for more than two hours.

It’s kind of unusual these days for a star to hit the road. In the old days you’d have an actor or a director coming through town every week. These days, most interviews are on an assembly line. The studios enthrone their stars in a hotel on one of the coasts, and lob journalists at them like human sacrifices.

Going on the road was her own idea, Foster said. “Nell” was not only a movie she starred in, but the first film from her own production company. So she wanted careful attention paid to it. “I didn’t want it to be stuck on a publicity production line where the press goes on a junket and someone hands them the stupid hat and the T-shirt and the blower or whatever it is and it just feels like another hundred movies. I just feel like a different thing happens when you have the time to really talk to people about what you think the movie is about. Because you get into this six-minute sound bite thing and it becomes shameless promotion. It’s really about buying prime-time TV. It’s not about the film.”

Yeah, I said, when you do 20 interviews, and each one is five minutes long, it’s a little like a nightmare where you’re trapped inside “Entertainment Tonight.”

“I grapple with that all the time,” she said. “I ask myself, am I an insincere person because I can do these little sound bite things, condensing the pitch into 30 seconds? You have to make peace with the process and so I only promote movies I care about. If I did it for a movie I hated or had no connection with, then I would really feel like an impostor.”

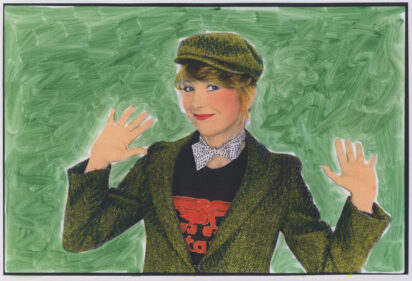

I look at her, and listen to her, and I remember. Twenty years ago, when she was 12, I interviewed Jodie Foster for the first time, about a Martin Scorsese movie named “Taxi Driver.” The deal was, we would meet for lunch at a health-food hangout on Sunset Boulevard. I expected her to turn up with her mother and her manager and a publicist and a makeup person, but she turned up all by herself, ate a spinach salad and talked about the movie.

There was some controversy over her role in “Taxi Driver” because she played a street waif who had become a prostitute. Would the role damage someone so young? Five minutes of talking with Foster (who had started in toothpaste commercials at 3and starred in movies since she was 8) and I knew I didn’t have to worry, not about her, anyway. She was telling me about her discussions of directing with Scorsese and her observation of Robert De Niro’s acting style. And a few months later, when the film played at the Cannes Film Festival, she sat calmly at a press conference in front of 500 people and translated everything into and out of French.

So she’s smart. That we know. What we know now, 20 years later, is that she has survived: She seems to know how to guide her career through the shoals of Hollywood, where there aren’t often great roles for women, but she makes them happen for herself.

Her Academy Awards have come for “The Accused” (1988), where she played a rape victim, and “The Silence of the Lambs” (1991), where she was an FBI agent up against a brilliant serial killer. The same year she made “Silence,” she also directed her first film, “Little Man Tate,” and played a working-class mother trying to deal with the fact that her son may be a genius. The project may have indirectly reflected her own relationship with her mother, who has been both manager and friend.

Now her work in “Nell” will undoubtedly win her another Academy Award nomination in February. She plays a wild child, the surviving member of a set of twins, who has been isolated all her life in a North Carolina wilderness with her dysfunctional mother. Nell can take care of herself, and she can speak, but her language sounds like a strange sing-song of nonsense, with the haunting pattern of familiar syntax buried somewhere deep inside. And her body language is that of someone who has not seen a person her own age for a long time, except in a mirror.

Foster bought the rights to the Mark Handley play “Idioglossia,” which inspired the screenplay. She changed the sex of its subject from male to female. She found the director, Michael Apted, who had explored the rural South for “Coal Miner's Daughter.” She was able to hire Liam Neeson for his first role since his milestone performance in “Schindler's List.” And for the other lead she wanted Natasha Richardson, not so much because she was Neeson’s wife as because Natasha and Jodie had become friends years earlier, when Foster starred in “Hotel New Hampshire,” directed by Richardson’s father, Tony. You look at the parts that went into “Nell” and you’re not surprised that you’re impressed by the whole.

“Liam first came to us and really wanted to play the role,” she said. “For me, the only reason to have somebody in a film is if they love it. And he’s not afraid to be sensitive, which was crucial. Natasha’s so intelligent, and you can’t hide that on the screen. She doesn’t have to wear spectacles to be smart. She just is, so she can play the vulnerability underneath.”

In the film, Neeson is a doctor who is led to the newly discovered “wild woman” living in the wilderness. Richardson is a psychologist. Only gradually do they crack the code of Nell’s language and see that she is not retarded, merely very different. And that she may have lessons to teach them.

“Otherness is a big thing for me,” Foster sad. “I’m always drawn to characters that live lives that I couldn’t lead. People who survive and don’t allow the world to change them. Maybe this movie will give someone the idea that if Nell can be herself, maybe it’s OK for them to be brave, too, about their idiosyncratic natures and their otherness.”

You’re so verbal, I said, that I don’t know how you found a way to play this woman who can hardly communicate at all, and speaks no known language for much of the movie.

“I was petrified. I didn’t know what I was going to do. I did the research thing; but it didn’t pan out. How can you research Nell? Finally I realized all I really had to do was just be emotionally available. And that meant no hair, no makeup, no costumes, no props, no other person to talk to. You’re on your own and you just have to find an emotional connection to everything. You drink a cappuccino, hang out with the guys. Then someone says action! and you just do it. I don’t think there’s any more preparation than that.”

In the film, she talks to herself, repeating what sound like empty syllables until Neeson and Richardson make a breakthrough. And she moves with an eerie choreography.

“Everything depends on Nell’s situation. If Liam moves his hand up, then that changes my performance. If he starts talking or something comes out his face, that is going to change my performance. It’s not like I’m supposed to do this or that. But underneath there is a very complicated script with very complicated language and everything Nell says makes sense, and I could tell you what it all means. By the end of the film, the audience understands everything.”

Working with Michael Apted, she said, was fairly simple, because he doesn’t theorize about a movie. The director of the famous British “7-14-21-28-35 Up” series, which has been visiting the same group of people every seven years since they were 7, he goes from such documentaries to thrillers like “Blink” and epics like “Gorillas in the Mist.”

“The only question that he will ever ask is, `Is it real or is it not?’ If was making a movie about boring people who only watched TV, it would be the most boring film you’ve ever seen. He wants the story to tell itself and he wants the characters to tell their own story. What makes him right for a movie like this is that he will never kind of, like, typecast the movie and say, `The head of the clinic is the bad guy so I’m going to cast some bad guy, J.T. Walsh or whoever. . . .’ The only thing he asks is, what are these people like, who are they, what do they believe?”

A third Academy Award? What do you think?

“Well, you know, when I was a kid and we all sat on the bed and ordered a bunch of Chinese food, and everybody would talk about the Oscars, it never occurred to me, ever, that I would get one. The idea that somehow I’m one of them is so foreign to me, I can’t even believe it. So I’m not gonna get too excited because I don’t want to be disappointed if I don’t get nominated.”

The reviews on the picture, I said, seem to be basically good. . .

She grinned. “You know what I hate? This is the only thing that will make me write a letter to a critic. I don’t like it when reviews aren’t about the movie. When they’re about how much money somebody made, or who they’re sleeping with, or if they got the job via some connection, or about how Fox is putting X amount of dollars into it. The review just turns into this whole corporate thing.”

If you were a critic, what would you have praised this year?

“Well, `Pulp Fiction.’ I actually sort of enjoyed it. I mean, I’m not wild about it. But with `Natural Born Killers’ . . . you look and you go, my God! The mixing! My God! The direction! The photography! But then you ask yourself, what end does it serve? It’s like Oliver Stone was saying, `I’m an incredible drummer and I can go like this for an hour and a half and do stuff that no one else can do!’ But who cares? It felt to me like a betrayal to the talent of the people that were involved to have it go to such an incredibly inhuman end. I didn’t get it.”

When are you going to direct again?

“Right now. A film with Holly Hunter called `Home for the Holidays’ which is sort of a comedy that turns into a drama, about a woman who, on the worst day of her life, with all this terrible stuff happening to her, has to get on a plane and go to her parents’ house for Thanksgiving. Basically, the entire second act of the movie is around a table with a turkey and all these secrets unfolding and everybody hating each other.”

You’ve had some moments like this in your life?

“It was a great thing for my mom the day we all just said, like, `You don’t ever have to have Christmas again – because one of us will, and then you can just come and bring wine and you can feel like you’re a guest.’ It was liberating for her, and for us, too. I realized I could have my own Christmas. I could invite my mom and say, `If you want to come, that’s great. But you can’t complain about my linen, because it’s my house!’ ”

You’ve had a good relationship with your mother?

“Oh, yeah! It’s great. And now it’s better because she’s a friend.”

That’s a true family statement: “It’s great, and now it’s better.”

She smiled. “It’s better because you don’t have the same old issues. You’ve gone through the hard times and you’ve figured out how to turn it into something more healthy for both of you. I get along with her so much better now that she knows I’m not going to go out there and stub my toe 24 times a day.”

She still worries about you?

“She has so much fun worrying about my siblings now that I’m off the hook for a while. I went to my sister’s and they had like this big soap opera because my sister decided to cook with her ex-husband, for her husband and everyone else.”

With her ex-husband, for her current husband?

“Yeah, because her ex-husband is a really good cook. And they love to cook together and his wife just left him so he didn’t have anybody to be with for the holidays and she had the kids for Thanksgiving and he was going to be alone so she said, well, maybe he should come. And my mom is just sitting in the middle there going, `Ummmm,’ and saying things like, `That’s my favorite son-in-law.’ Wreaking havoc.

“I’m like watching her and I went up to my sister and I just said, `I’m so glad that you’re having the drama this year because I get to, like, leave completely unmolested.’ ”

And you were thinking while you were sitting there that you were directing “Home for the Holidays.”

“I was. And it’s funny. I’m not sure my mom really likes this movie very much. She hasn’t talked about it yet – which has to mean that she is somehow offended and doesn’t want get into it. Finally I said, `Obviously, you don’t like it because you haven’t had some kind of opinion about it.’ And she said, `It’s very cute.’ So, I’m waiting. You know, I steal from people constantly. It’s true I stole a lot of things that she said, but it doesn’t mean that the character has anything to do with her. I can tell she’s definitely miffed, but. . . .”

She shrugged. “It’ll all be all right if it’s a good movie.