“There wasn’t any one single horrendous event,” Kim Darby was saying, thinking aloud. “And I never said to myself, all right, I’m going to drop out. It just sort of happened more naturally. I decided to stop running from here to there, and sit down with myself and do a little thinking. You know what I wanted to do? I wanted to wear myself better.”

And so, after working steadily as an actress since she was 14, Kim Darby stepped aside for almost three years. She spent a lot of time with her daughter, Heather, who is 9. She didn’t read scripts or even think much about them. “I thought it was time to step back and get to know myself better,” she said. “I wanted to own my own feelings, instead of feeling fear and anxiety that really had nothing to do with me.”

She was talking in a low voice, and she was so sincere it was almost heartbreaking. She was one of the first actresses I’d ever met, back in 1968 when she was costarring with John Wayne in “True Grit.” And I thought to myself that in the 10 years since then, I’d heard a lot of second-hand psychological phony baloney from performers who wanted to get in touch with themselves and who were signing up with gurus or dropping out, or in, or up or down… but that Kim Darby wasn’t like that. She stopped acting for a time because she really did want to figure out who and where she was.

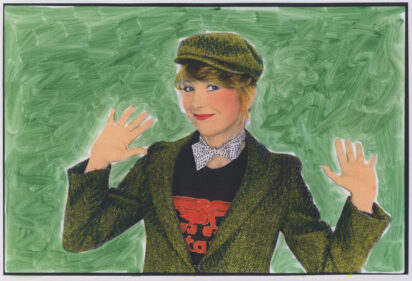

She looked great. She was sitting on a couch in her suite at the Continental Plaza, nibbling at a plate of cottage cheese and looking up with those big, clear eyes that weren’t afraid to stare down John Wayne or anybody since.

She’s in a new movie. It’s called “The One and Only,” and everybody is referring to it as Henry Winkler‘s new film, because Da Fonz is a television superstar. And maybe people will come out of the theater trying to remember where they’d seen that actress before, the one who played his wife. Kim Darby is afraid it’s likely they’ll remember her as a victim from one or another of the made-for-TV movies she’s done.

“One thing I decided while I was re-evaluating things,” she said, “was that I absolutely wouldn’t play a victim ever again. I was the one they always called for the woe-is-me role. It’s funny: In ‘True Grit,’ I was pluckier almost than John Wayne. And so how did I get typecast as the threatened female? There was this whole period on television where women were being pursued and preyed upon and there I was the greatest victim of all. People have got to eventually get tired of seeing that stuff. Look at all the great movies about women in the past year. They’re letting women be people again.”

She nibbled at some cottage cheese. “What was your favorite movie last year?” she said.

“I always say ‘Nashville,’ because I always think it’s still 1975,” I said. “It was ‘3 Women,’ and I had to see it three times before I knew how much I liked it.”

“Mine was ‘Annie Hall‘,” she said. “Followed by ‘The Goodbye Girl,’ because I know a thing or two about bringing up a child alone.”

“Would you like to work with Woody Allen?”

“Oh, God. I’d love to.”

“Why,” I asked, “would every actress in America kill to work with Woody Allen?”

“It’s simple. He’s sexy.”

“Woody Allen?”

“He seems real vulnerable, and it’s really attractive to see that in a man. Macho wears very thin very fast, and a little goes a very long way. But Woody… he’s so bright, and then he’s so vulnerable…”

Sigh.

“I would have liked ‘The Goodbye Girl’ a lot more,” I said, “if the actress had been someone like you, instead of Marsha Mason. I didn’t think she made the role attractive enough: What was it that Richard Dreyfuss saw in her?”

“Well,” Kim Darby said, “I saw plenty. Raising a daughter by yourself is a big responsibility. I have to think about that in terms of my career. I just turned 30, and I have to be very careful to pick the roles that will be good for me, and all the time I’m also thinking that I have a responsibility to Heather and myself, because we do have to eat.”

“You’d just had Heather when you made ‘True Grit’.”

“Just had Heather. I started the picture two weeks after she was born. I turned down the role three times. But Hal Wallis, the producer, kept after me. And I finally took it not only because it was a wonderful role, but for some personal reasons, too. Because I had to think about supporting us.”

“You’ve been divorced from James Stacy for eight years?”

“That’s right.”

“So you must have been divorced soon after Heather was born?”

“Real soon.”

“Are you Irish? Where’d you get the name Heather?”

“It was just the nicest name I could think of. I still think it is.”

A small silence. Some cottage cheese.

“Everybody thinks ‘The One and Only’ is about wrestling,” she said. “Actually, it’s a love story. It’s about wrestling in the sense that Henry Winkler’s character will do absolutely anything to get into show business, and ends up as a Gorgeous George type. But I love the relationship. The woman I play is a real grown-up. She’s very much in love and very scared. But when it becomes not good for her to stay with him, she’s courageous enough to leave. And when they get back together again, it’s for the right reasons, not sappy ones.”

I mentioned that “Heroes” and “The One and Only” were both movies in which Winkler deliberately did not play a character resembling, Da Fonz.

“He walks down the street,” she said, “and people shout, Hey, Fonzie! And he says, no, he’s really Henry Winkler. Really. He doesn’t want to play the Fonz, and I don’t want to play any more victims, so this was a pretty good movie for both of us… I went to see it the first time, and I was so nervous and excited I missed half of it. The second time, I really liked it. It’s about, you know, sweet people. She loves him in the best sense, and she wants to make him happy.”

And what about you? What did you decide during your three years off?

“Some good things. That in my acting I like to work with people and see them do better and get happier, and I want that for myself, too. And that I’d like to get married again.”

Sigh. I tried to look as vulnerable as I could, but I guess Woody still has the inside track.