In 1945, his sixth year in the Army, John D. MacDonald sent a short story home to his wife. She typed it up and submitted it to Story magazine, which bought it for $25. “1 thought that was pretty damned good,” MacDonald recalls. “I figured, hell, if I could sell about four stories a week, I could live pretty well.”

As of last week, MacDonald had sold about 65 million books, and he lives pretty well. Visiting Chicago to speak to the American Library Assn. convention, he was deep-voiced, tanned, friendly. He looked so much as if he lived on a Florida houseboat (like his most famous creation, Travis McGee) that somehow I even forgot to ask.

MacDonald isn’t simply popular; he’s also good. Connoisseurs of detective fiction generally consider it a toss-up in quality between the two best-selling MacDonalds – John D. and Ross (who spells his last name with a lower-case D, and is very definitely no relation). Their characters, Travis McGee and Lew Archer, have become the literary heirs of Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe. And if McGee is more hard-boiled and Archer more contemplative, they both share the gravest reservations about human nature.

MacDonald, who says he sometimes chafes at the limitations of the first-person detective novel, does other kinds of books between the McGee adventures. “There have been 66 books altogether,” he says, “and 16 have been about McGee. The first McGee came out in 1964. The character was originally named Dallas McGee–but then, after the assassination, that had the wrong connotations. My neighbor down in Sarasota, MacKinlay Kantor, suggested I name him after an Air Force base. I thought old Mac had finally lost his wits, but I went through an almanac, and there was my name.”

McGee is a free-lance investigator who works out of the Busted Flush, a houseboat operating mostly in Florida waters. His adventures usually begin just as he’s looking forward to a brief retirement (which he takes a few months at a time, on the reasonable grounds that he’s unlikely to survive long enough to enjoy it all in a bunch at 65). He’s frequently sitting on the deck of the Flush with his best friend, Meyer, drinking his favorite cocktail (pour Dry Sack over rocks, swirl, throw out, cover rocks with Plymouth gin), when a woman enters, scared and uncertain.

“The plots invariably fall into a pattern,” MacDonald observed, “but I try to keep it as unobtrusive as possible. For example, at the end of every book, you have to get rid of the protagonist lady. They all fall in love with Travis, and if I didn’t get rid of them they’d clutter up the Flush and he’d find himself in a new line, of work.

“The introduction of Meyer was also an attempt to get away from the limits of the first-person thing. Meyer wasn’t in the first couple of books, but I found Travis running into many interior monologues, or talking too much to people he wouldn’t talk that much with. So I wrote in Meyer. Travis needed a Tonto.”

One of the things he likes about the detective genre, MacDonald said, is that it gives him a captive audience for his favorite parts of the books, the asides. “I can have the hero hanging on a ledge with somebody pounding on his knuckles with a hammer,” he said, “and I can go off and make a comment on something in the world that’s bugging me, and when I come back, the readers will still be there.

“I read to the librarians, for example, a passage from the 17th McGee novel, which is back in Sarasota about half done. It’s about how TV can become a kind of automatic peer group approval. Here’s this creep who goes out and burns puppies, and he comes home and Sonny and Cher will still be risking hemorrhages singing and dancing just for him.”

The McGee novels have had an unusual publishing history. They began as Fawcett paperback originals (all still in print), gained enormous popular success and then belated critical praise. Now the newest ones (“The Turquoise Lament,” “The Dreadful Lemon Sky”) have had their first publication in hardback, and Lippincott has republished the first 14 between hard covers.

“The old ones are selling about 10,000 to 14,000 copies each, a lot of them to libraries which wouldn’t have dreamed of buying the paperbacks,” McDonald said with relish. But despite his millions of sales and critical respectability, he continues to work hard.

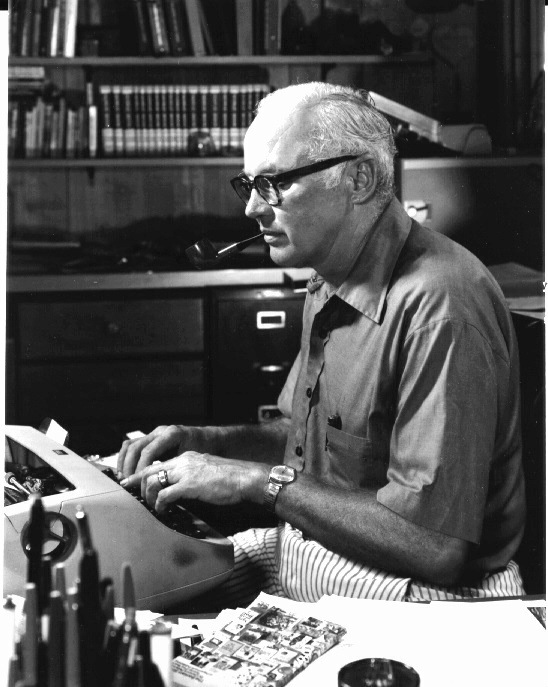

“I start about 9 in the morning, take a break for lunch, and finish about 5:30 in the afternoon,” he said. “I put in a full working day. Sometimes the last five or six pages won’t come out right and I’ll rewrite them in the morning.”

MacDonald is in the second generation of major American detective novelists, after what he calls “the big boys”–Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett and James M. Cain.

“I got a call not long ago from the New York Times asking me to review the new Cain novel,” he said. “My first reaction was, is he still alive? Must be in his 80s. I read the book and it’s a…well, it’s impossible. All about Swedish maids with vibrators. What was I gonna do? I was fair to the book, I thought. And then they sent me $150 for the review, which had honestly never occurred to me. Being paid for it, I felt in some way I’d betrayed the SOB. He was good. I owe a lot to him.”

Among the contemporary detective novelists, I said, isn’t it strange that you and Ross McDonald would both have the same last name? John D. MacDonald paused for a moment. “Even more strange,” he said, “is the title of his new book, ‘The Blue Hammer.’ Now what does that make you think of?”

One of your McGee books, I said. They always have a color in the title.

“I wrote him,” he said. “I said, ‘no doubt this is innocence on your part, but people are going to think it’s meretricious.’ He didn’t reply. I must confess I feel a little irritated by that.

“God knows we have enough trouble keeping our identities separate. Thank God the guy writes as well as he does. He could be some real plumber. I don’t want to feel victimized, but it comes down to this. I wouldn’t do it to him.”

You could almost hear Travis McGee.