“Directing really turns me on,” Russ Meyer was saying.

“I get involved in a scene, and I’m down on the floor looking through the viewfinder, shouting instructions to my actors, to my crew, and don’t bother me then, baby. We can shoot the scene again tomorrow, but don’t hassle me now.”

Meyer sipped his drink — water on the rocks — and smiled. “That makes the difference in our films,” he said. “I care.”

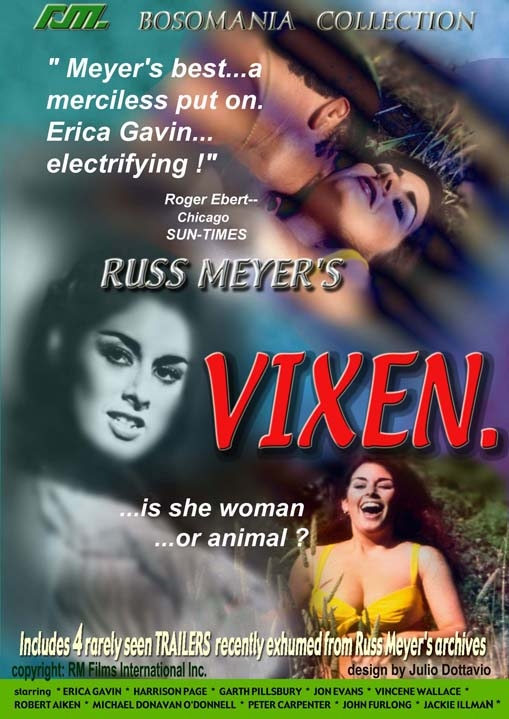

Across the room, Oscar Brotman was talking to a press agent. Brotman opens Meyer’s new film, “Vixen,” in the Loop Theater Friday. “Level with me,” Brotman said to the press agent. “What do you think about this film? How will it do?”

“Oscar,” the press agent said, “you book this picture, you won’t have to book another picture for a year.”

“I don’t know,” Brotman said. “You think I’ll get busted? You hear about this Grand Playhouse deal Wednesday night? I don’t know who it is, but it looks like somebody’s all excited, somebody called the mayor or something, I don’t know. I called up the censor board, and I said, come and look at this picture. They said nothing doing. I’m showing it to adults only; it’s out of their territory. So now I hear these stories somebody’s got a bug in his ear, we’re going to get arrested.”

“But the picture’s not obscene,” a reporter said. “The picture is legally not obscene, Oscar. There’s nothing in ‘Vixen’ that hasn’t already been shown in a dozen movies all over the Loop. If a picture like ‘Barbarella’ can play, a picture like ‘Candy,’ what are you worried about?”

“I don’t know,” Brotman said. “But I’ll tell you the truth, I saw this picture and I like it. What I’m saying is, I don’t play these cheap pictures, these four-day wonders. I don’t play these trash pictures they make in a motel room over the weekend. But I saw this picture and I said, hey, this is a good picture. The color’s good, the production values, the acting, the directing, and you know what? It’s a funny picture, too. I personally dug this picture…”

The press agent engaged Brotman in a detailed discussion of recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions involving obscenity. A human wave broke across the crowded cocktail party, and Meyer was washed up against a wall. He is a big man, well over six feet, with a Victor McLaglen mustache and a disarmingly direct manner. He learned cinematography as an Army cameraman during World War II.

“There was this article in True magazine this month,” Meyer said. “It was a good article, it will sell tickets, but –” he lowered his voice, “I have a hunch the guy who wrote it is a little on the pink side. Stanley Kramer and I were in the same outfit in the war. This guy writes that now we are both directors, and Kramer is in charge of world peace but I’m in charge of anti-Communism.”

He laughed. “I guess you could say that,” he said. “I am a rabid anti-communist. But ‘Vixen’ is also against airplane hijacking. And it supports racial understanding. And it’s a strong picture, you know what I mean?”

Apparently the word has gotten out. During the last few weeks of the “Les Biches” engagement at the Loop, between 15 and 25 customers a night have paid admission to go in, catch the coming attraction trailer for “Vixen,” and leave without even seeing the feature. No wonder. Like all of Meyer’s films, “Vixen” features uncommonly endowed young ladies in age-old situations.

What Meyer’s films also have is an uncommonly high level of artistry. In professional filmmaking circles, Meyer is known as the one creative director in the sexploitation field. His competitors churn out slipshod low-budget films exploiting the nudity of their actresses (who usually look hideous enough to inspire cries of “put it on!”). But Meyer budgets his films at around $70,000 — or 10 times the usual level — and rehearses his cast for a month before shooting.

Another Meyer trademark is shooting on location; “Vixen” was shot during five weeks in British Columbia. This costs money, but it makes money. In an article crowning Meyer as “King of the Nudies,” the Wall Street Journal reported last April that his first film, “The Immoral Mr. Teas” (1959) has now grossed $1,200,000 on a $26,500 investment. That’s a 40-to-1 return, the Journal observed, second in film history only to “Gone With the Wind.”

Meyer’s subsequent films have done nearly as well. Both “Lorna” (1963) and “Eve and the Handyman” (1961) have grossed nearly a million, and not one of his 20 films has failed to return four times its original cost. In the South and Southwest, exhibitors would rather have the new Meyer movie than a John Wayne Western.

“Vixen,” which Meyer describes as the “most advanced” film he’s made, outgrossed every other film in Atlanta for several weeks. “Except one week,” Meyer said. “We were in a 278-seat theater, and ‘Coogan’s Bluff’ opened in a 1,400-seat theater and did one dollar more business its first week.

Meyer’s commercial appeal is explained, perhaps, by his lavish display of actresses. But Meyer’s artistic and critical stature is not so easily explained. The French critics like to talk about their “auteur,” or film author theory: Great directors can be identified because they place the unmistakable stamp of their own personality on every foot of film.

This is true, the French say, no matter what genre the director is forced to work in for economic reasons. A Howard Hawks Western, a Don Siegel police drama, can be as great as a Fellini or Bergman film, they argue; it’s just that Americans are such snobs they prefer foreign “art” to the domestic variety.

Under this premise, Meyer is perhaps the last great undiscovered American director. His films are limited by their genre (familiarly known as the “skin flick”) and by their budgets, but a consistent artistic vision dominates them. They are fast-paced, usually well-acted, directed with a joyous zest, and they deliver the goods.

“Out on the coast,” Meyer said, “they have what they call beaver movies. You know. But I have never gone into this area and I never will. It’s not attractive. I like good, clean, wholesome sex, strongly plotted, with a sense of humor. A lot of the second-rate guys in this field believe that if you undress a babe in front of the camera, that’s sexy. They’re wrong. What’s sexy is the situation.

“You have to have the buildup, the dialog, the camera angle. You have to establish characterizations, so the scene will be convincing. You can’t just let the camera run. Timing is crucial, and editing is crucial. The way you edit a scene makes it work.”

Meyer usually edits by juxtaposing his sex scenes with incongruous scenes of something else. A psychiatrist might call this transference. In “Finders Keepers, Lovers Weepers” (1968), for example, his heroine has just finished shaving the hero’s chest. (“I put it in for the hell of it,” Meyer said. “Can you imagine?”)

The hero, aroused, advances on the heroine. “But can’t we wait?” the heroine asks. “I want to go to that symphony tonight…Erich Leinsdorf is conducting Maxim Gorky’s Prelude in D Major.” Then Meyer cuts to shots of a stock car destruction race.

Meyer’s symbolism is not obscure. Nor is his approach to a scene. He likes well-lighted sets, decorated in basic colors, and simply defined. In “The Immoral Mr. Teas,” he introduced surrealistic sets for the dream sequences. One of the entertaining aspects of his work is that he often goes for the humor in a scene rather than the sex (“I’m a W. C. Fields fan from way back,”). Reviewing “Mr. Teas” for Show magazine, critic Leslie Fiedler found it a comic masterpiece.

“Eve and the Handyman,” which has long since lost steam as a sexploitation film, is revived by college film societies who dig Meyer’s use of silent comedy sight-gags.

Meyer’s survival as an independent producer is phenomenal. He has lasted 10 years in the most hotly competitive genre in movies, and dominates an adult film market totaling 400,000 admissions a week in 900 theaters. The field is jammed with imitators; Meyer is the only innovator.

He invented the American nudie with “Mr. Teas.” He correctly predicted the demise of voyeur-oriented nudies in 1963, and made the first roughie, “Lorna.” He also made the very first motorcycle picture, “Motor Psycho” (1965), a year before Roger Corman‘s “Wild

Angels.” He directed the first big-studio sexploitation film, the $450,000 production of “Fanny Hill” (it starred Miriam Hopkins, who once reminded Meyer that after all she’d been married to Fritz Lang).

And now, with “Vixen,” “Finders Keepers, Lovers Weepers” and a film in preparation, “Cherry,” he has crashed the respectable first-run theaters with work made in the spirit of big studio products like “Candy” and “The Killing of Sister George.”

“It’s getting harder and harder to stay ahead of the majors,” Meyer mused. “What I do today, they do tomorrow.” In many of his films before 1968, Meyer relied on an asset the big studios didn’t have or couldn’t locate: Actresses with spectacular endowments. One film, “Common Law Cabin” (1966), starred three girls whose measurements, Meyer’s ads claimed, were 44-22-36.

“We made a movie ‘Erotica,’ that had the most incredibly built girl you’ve ever seen,” Meyer recalled. “I mean beyond belief. Hugh Hefner screened it called me up. ‘My God, Russ,’ he said, ‘How big is that girl?’ Hef, I said, she goes right off the scale. We have to use hat sizes.”

But with “Vixen” and “Cherry,” Meyer is scaling his girls down slightly. “The big undeveloped market for us right now is the female audience,” he said. “The reason ‘I, A Woman’ did so well was because women wanted to see it. But a woman can’t identify with an actress who’s unreasonably built. My actresses will always be built but not unreasonably, you know?”

The experiment has been successful. The star of “Vixen,” Erica Gavin, is well built but…not unreasonable. The role gives her considerable opportunity to display a capable acting talent, and on the basis of “Vixen” Miss Gavin has been signed by the large Hollywood agency, Talent Associates. One of her co-stars, young black actor Harrison Page, got roles on “Bonanza” on the basis of “Vixen.”

Other Meyer stars have also gone on to steady employment. Stephen Oliver, a Peyton Place regular, got his first break in Meyer’s “Faster Pussycat! Kill! Kill!” (1966), and Rena Horton of “Mud Honey” (1964) is currently appearing in “Paint Your Wagon.”

Meyer himself has received big studio offers. “American-International wanted me to direct some of that beach blanket bingo bull crap, but I refused,” he said. “The only film I’ve made that wasn’t entirely under my own control was ‘Fanny Hill,’ and I wasn’t satisfied with it. I stay with my movies from beginning to end.

“I invent the plots myself, usually while I’m alone in the car. I have a clipboard and a felt tip pen and I jot down things that turn me on. I assemble these situations in my mind, I imagine how they develop. Then I bring in a writer to put it into script form. But it’s all right here.” He tapped his head. “It’s all right here, and it’s me.”