“I’m really a director now,” Maximilian Schell was saying. “That’s how I’ve thought of myself for the last few years. It’s just that once in a long while a role comes along that I simply can’t turn down. This was a role like that – how could I say no to it?”

The role was the title role in “The Man in the Glass Booth,” Robert Shaw‘s drama about a man not unlike Adolph Eichmann, who is returned to Israel and tried for war crimes. But the man, Albert Goldman, is unlike Eichmann in one important respect: He is mad, and immensely complicated, and he is hidden in a maze of identities so thick that no one knows for sure who he really is.

“The Man in the Glass Booth” was first released earlier this year as part of the second season of the subscribers-only American Film Theater. It was a critical success, as most of the AFT offerings have been, and originally the AFT planned to hold it off the market for at least three years. But the AFT’s revenues for its first two seasons were below expectations (partly because of a ticket computer’s foul-up the first year), and in an attempt to steady itself financially the AFT is releasing “The Man in the Glass Booth” for an earlier commercial run. It opens Friday at the, Carnegie.

Although Schell is Swiss, he’s often thought to be German and does most of his work there. And his career’s high points have often revolved around films dealing with Germans of the Second World War period. He won the Academy Award as best actor in 1962 for his portrayal of a government prosecutor in “Judgment at Nuremberg.” He played a Nazi war criminal in last year’s “The Odessa File.” “The Pedestrian,” the second film he directed (and a winner at our Chicago Film Festival), was about a middle-aged manufacturer confronted with evidence that he murdered Greek civilians during the war. And now comes “The Man in the Glass Booth.”

“There does seem to be a pattern in all those films,” he said during a recent interview here. “It’s not that I’ve typecast myself – I’ve played a lot of other roles – but that I think there’s an area of subject matter here that has to be faced and seriously dealt with. ‘The Pedestrian’ was the first German film, after all these years, to deal with the subject of war crimes. Perhaps there was a feeling that Germans didn’t want to see films on that subject, but in fact it was a great critical and commercial success in Germany, and won a $150,000 prize from the government.”

He said he admired “The Man in the Glass Booth” as a play, and when the American Film Theater offered it to him as a film he felt compelled to do it. “It’s a very strange, difficult role,” he said. “It has to be understood from the first that Goldman is insane – but in a way that’s intimately involved with his past. The play deals with so many aspects of identity. Is Goldman, for example, really a Nazi criminal posing as a Jew? Or is he a Jew who posed as a Nazi to escape the prison camps and was swallowed up in that identity?

“Thirty years after the war, his dreams are still disturbed by memories of Dorf, a prison camp commandant. But did Dorf really exist? Or did Goldman create him? We never know for sure. So much depends on how I portray Goldman, so that the audience thinks one thing about him now, and another thing a few scenes later. It all has to be very theatrical and crazy. Sink to the level of realism and you’re lost.”

The film was reviewed in The Sun-Times when it played in the AFT season here last January. Awarding it three stars, I wrote in part that “The point of ‘The Man in the Glass Booth’ isn’t really to answer the question of Goldman’s identity. It’s to pose disturbing notions about the nature of human identity, guilt and responsibility. And it’s to illustrate the ways in which the holocaust was a wrong of such monstrous evil that individual personalities could be obliterated by it. Films like ‘Judgment at Nuremberg’ began with the assumption that morality could be upheld and responsibility assigned. ‘The Man in the Glass Booth’ is an infinitely more despairing work.

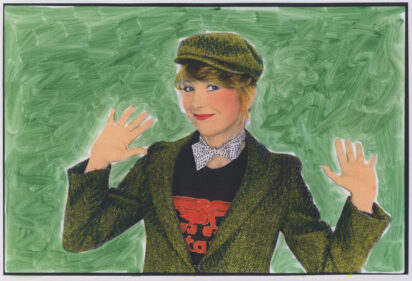

“Arthur Hiller‘s film for the AFT is a very good one, although it suffers from one basic problem. By its very nature, film tends to be a realistic medium, photographing the outsides of the real world. Robert Shaw’s play, even as adapted and made somewhat more realistic by Edward Anhalt, is nevertheless a symbolic and mannered one. Situations and dialogs that work within a stylized stage setting sometimes seem incongruous, affected, in this objective film world. “The man in the booth, whoever he is, is played by Maximilian Schell…who creates a personality here that fits his character’s tortured dialog and projects a special madness in scenes where his logic leads to inhuman conclusions…. Without ever seeming to explain, Hitler quietly leads us into his world, and into a story which can finally end only when Goldman kills Dorf, or Dorf kills Goldman, or they die together.”