Many words come to mind when describing the films of Alejandro Jodorowsky. Everything from “surreal” and “hallucinatory” to “grotesque” and “violent.” But “autobiographical” is usually not one of them. And yet, here we are, with Jodorowsky’s first film in 24 years, “La Danza de la Realidad (The Dance of Reality)”, a myth-inflected memoir of his family in 1930s Chile. Telling the tale of unhappy, suicidal Alejandro (Jeremías Herskovits) and his larger-than-life parents—his father Jaime (Brontis Jodorowsky), attempts to assassinate the left-wing dictator Ibanez, while his mother sings all her dialogue as if it were opera—the film feels very much of a piece with the visionary director’s earlier, legendary work. Here, Jodorowsky’s magical realist, fable-like cinematic language finally enters the real world; if cult films like “El Topo,” “The Holy Mountain,” and “Santa Sangre” interwove elaborately absurdist imagery with narratives borrowed from genre and myth, “The Dance of Reality” feels like Jodorowsky returning to the scene of the crime—to the the childhood visions and heartbreaks that started it all.

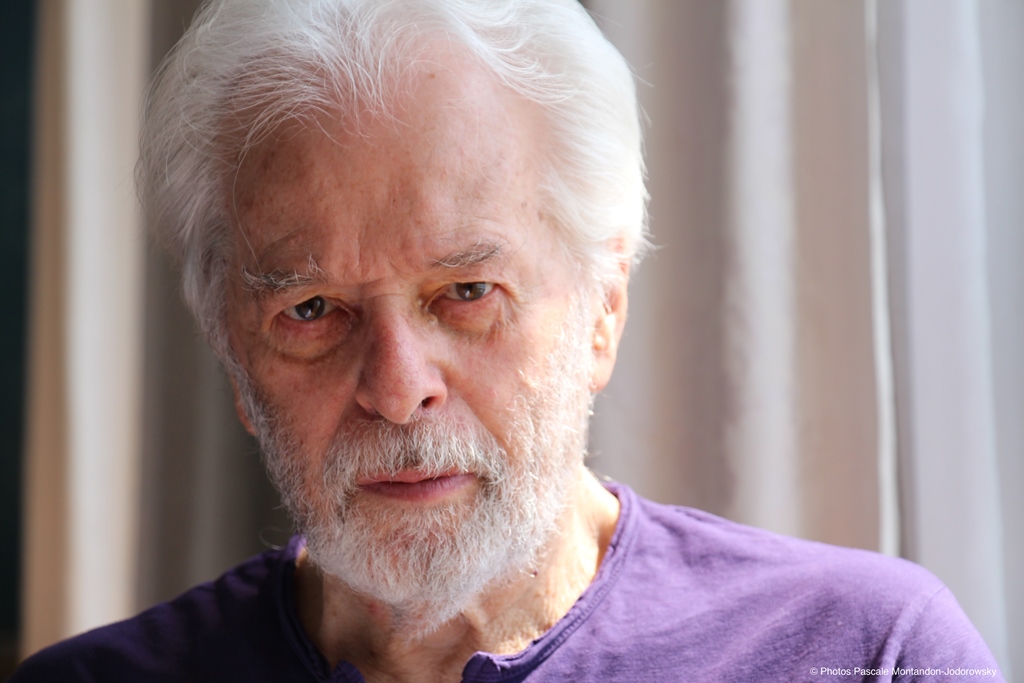

“The Dance of Reality” also comes at a time of increased exposure for the filmmaker. Another film, “Jodorowsky’s Dune,” Frank Pavich’s documentary about the director’s ambitious, abortive attempt to adapt Frank Herbert’s “Dune” in the early 1970s, recently hit theaters. In it, Jodorowsky talks about making films as a spiritual battle, and calls his collaborators “spiritual warriors.” It seems that now, with a documentary and an autobiographical film, with a new memoir set to be published in June (“The Dance of Reality: A Psychomagical Autobiography”) and a popular Twitter feed, this once-enigmatic filmmaker has opened himself up to an international public in ways previously unthinkable. I recently sat down to talk with him in New York, on the eve of a MoMA screening of his latest film. As you can see, the conversation soon went on to other matters: The “poison” of stardom, the quest for happiness, the power of art to heal, and much, much more.

So how much of this film is autobiographical?

ALEJANDRO JODOROWSKY: Everything in the film is true, but it’s explained with the language of art. It’s about a child who’s thinking, but at the same time it’s an old person who’s guiding, so it’s a mix. But both characters are me. And it’s all true. Even the place is true: I went back to the real town where I grew up. The town was exactly the same, because it’s a dead town. Everything was the same—except for my house, which had burned down. So I reconstructed that. And I give it to the town. It’s for the tourists now. It’s there.

But your father never tried to assassinate Ibanez, the dictator of Chile, did he?

My father never went to kill Ibanez. But he wanted to do it. I wrote a book about that. I put it in the picture, so he was able to realize his dream. And my mother never sang opera. But she wanted to. So, I made her sing opera, because she wanted.

So, you’re redeeming your parents’ dreams with this film?

Yes. My mother was a humiliated woman. In the film, I make her get out of humiliation and to become the master of the family, and to sing. My father was a Stalinist. He dressed like Stalin, like in the film. And he dressed me like Stalin, when I was a child. And in the picture, he becomes human. He realizes he failed. He admired Ibanez, but he also hated Ibanez—because Ibanez was like Stalin, and my father wanted to be Stalin. That’s very human, for me. In the film, my mother says, “I love you for who you are. Not because you might be Stalin.” So now he understands. But in reality, he never changed.

Was this how you saw them as a child?

Yes. I was very conscious of their dreams. I was like a mutant when I was a boy. I learned to read when I was four years old; it was like a miracle. As soon as I learned, I started to read everything. At first, I was ashamed, because nobody else my age could read so well. So I started to make faults in my reading, so they wouldn’t know. One day, one of the boys threw a stone at me and broke my teeth. I had a terrible pain. At that moment, I said, I will read as I am. So, I picked up the book, and read. Brrrr, brrrrr. [Makes a speed-reading gesture] And they made me go to class with the big boys.

There’s a remarkable scene in “The Dance of Reality” where you, as a child, try to commit suicide, and then you, playing yourself as an older man, commune with your younger self to dissuade him.

Film is like poetry. I needed to heal my interior child. I suffered in that town. I wanted to go back and conquer that town. And I wanted to bring that child back, and to change my past. I came there to speak with myself. I shot this scene in the place where I wanted to commit suicide—in the same rocks. That scene is complete improvisation. I was in a trance. The boy was incredible. It is completely real. I really tried to kill myself. Why I didn’t kill myself? Because something made me not do it. I travel in time to save myself. I created a relationship between myself and my interior child.

The child is a non-professional. You seem to prefer non-professionals. Could you have done a scene like that with a professional actor?

I can’t do anything with an actor. I hate actors! They are poison! You cannot be free with stars. Even when the actor doesn’t want to be paid, because they want to work with you, they still bring ten persons—one who cuts the hair, one who brings their Big Mac, one who makes the massage. [Imitates an actor] “Oh, I need a close-up not from this side, but from this side. I can’t say this line…” Listen, I made a movie with three stars, a bad picture.

“The Rainbow Thief”? I like that movie. Peter O’Toole, Omar Sharif…

I hated Peter O’Toole. I wanted to kill that guy! When they said he was dead, I was happy. People said, “Poor Peter O’Toole.” I was happy! One day, he had to go eat an egg in this scene. He had to push away the eggs. We start to shoot, and he throws the eggs to me. I said, “All the persons out of the set!” I wanted to kick him. Everybody left. And then, for the first time, he was afraid. “What do you want? I will do what you want, not a problem.” All the stars have to show that they’re the master, they’re more important than you.

And the other guy, Omar Sharif. The woman who wrote the script was the wife of the producer. She was a little woman. In the morning, the make-up person would make her up. One day, Omar Sharif came and waited for the make-up. You feel he was thinking, “Why do I need to wait?” The executive producer had a car. Omar Sharif was in there, saying nothing. The producer went in there to speak to him. And Omar Sharif destroyed the car! He destroyed the interior of the car – everything. Yelling about what big testicles he has. We finished the shoot. He comes to the car. The owner is there. He says, “You destroyed my car!” Omar Sharif says, “Listen, I will pay for your car.” “But you destroyed my car.” “I will pay for your car.” “But you…” “Well, I’ll destroy your car again!” So, he takes a stick and destroys the exterior of the car. A second time! [Makes screaming sounds] That was Omar Sharif!

When I started to make the film, Omar Sharif would insult me. “Okay,” I say, “I will not speak with him. Everything I need from him, I will tell the assistant director to relay to him.” Then, I take a piece of wood, and put it next to me. I think, “If the guy insults me another time, I will hit him with this.” I think his assistant saw this and said something to him. Because then the assistant comes to me, and says, “Omar wants to stop that. He says you’re a very good director.” From that moment, he became a very good friend. But you can’t direct a guy like that. There is no poetry there. The producer says to me, “The most important thing are the stars, because they bring the money. If they have a problem, you need to agree to everything they want.” What kind of picture you can do with a star like that? Non-professionals don’t do things like that.

To get the freedom, you need the money. But to get the money, you need the stars. And when you have stars, suddenly you don’t have freedom anymore. It’s a vicious circle.

Or you can accept not to use the star, and have less money. For me, the important thing is not to lose money, and to be able to pay people. Why try to make a fortune?

Films like “El Topo” and “The Holy Mountain” were cult hits at the time of their release, but then they were unavailable for many years. But in recent years, there have been DVD releases, boxed sets, retrospectives. Do you feel your audience is bigger now than it was then?

For me, yes. But for the movies in general, the audience is now children who are going to see idiocies. For the majority of movies, it’s rotten. But for a minority, it is better. And that gives hope. This is why today I am showing my film at MoMA. I like to show my pictures in the museum. Pictures need to recover dignity. Pictures are an art.

You believe very much in the healing power of art. What were the films that healed you?

There are no pictures that heal me. Because I had a son who died 24 years ago. It destroyed me. But I still wanted to heal something—I wanted to heal others. If I cannot heal my son who died, I will heal the other son. My goal for art now is to heal. This is what I decided.

Is that where the idea of “Psychomagic” comes in? Explain how that works.

Yes. It came from there. I was studying Tarot, like a pleasure. I also study psychoanalysis: Erich Fromm, etc. With the Tarot system, you read the present like a test. You can find out something about a person immediately, in eight minutes. But in psychoanalysis it can take you two or four years, because you are speaking. Now, a man might say, “I want to make love with my mother.” I say, “Now you have an Oedipus Complex.” Now you know… but what do you do? The psychoanalyst might say, “Sublimation,” that sort of thing. He has no answer. But I need a solution. I realized that words have no solution. But an act has a solution. When you have this desire, you cannot sublimate it. You want to kill somebody, you want to fuck somebody…you cannot change it. You need to realize this desire. Kill somebody, fuck with your mother or father! You need to do it—but as metaphor, artistically. You need to take a photo of the face of your mother, put the face of your mother on the face of a woman, even if it’s a whore. Put the clothes of your mother on this woman, and make love to her, screaming the name of your mother. You need to kill your father? Put the photo of your father on a tree, and take a knife and put the knife into your father 100 times!

That’s probably where the whole idea of performance started, when you think about it. Ritual.

Yes! So now I give thousands and thousands of psychomagic acts to people, for every kind of thing. Still. I do it in Twitter now. People ask me, and I tell them what to do.

You’ve really embraced Twitter.

I will come soon to a million people. I have about 1000 new followers a day. I join Twitter because my son, who is a rock star in Mexico, said to me, “Why are you not doing that? That is our century. Why do you write alone? Write on Twitter. You can speak directly to a person, and they will answer you immediately. It’s a conversation. Do it.” I say, “All they do on Twitter is say they are eating a hot dog, or going to the bathroom, why do I care?” But I think, “No, I will use poetry, philosophy—like art. I will answer psychological and philosophical questions. Make something deep, spiritual.” And now, I think Twitter is the literature of our 21st century. Better than Haiku. I do it every day now. Every day, I make 15 tweets. Every day. I see it as poetry. I have a healing blog, too, in Spanish.

How do you find the time to do all this?

I am very organized, myself. At 12 o’clock, I write, the fifteen tweets. At 1:30, I answer questions. It’s like a ritual.

Have you always been this organized?

I was disorganized in the beginning. But when I was living in Mexico, I found a book in a library, “How to Organize Your Time.” I realized I don’t organize my time. There, I started to do that. Because if I don’t organize my time, I will not do anything. When you make a picture, you have to organize the picture, every time. Or you lose weeks.

You sound like a producer!

I say three things when I start a picture: “Listen, I know nothing of movies. I know what I want! So, stop with the technical things, and do what I want.” Second: “I am healing my soul. I will do whatever I want.” And third: “I have money only for seven weeks. Don’t go slow in order to promulgate and make more money. At seven weeks, I will stop. If I don’t finish the picture with the material I shot in seven weeks, I will finish what I have, then I will do a shot of me sitting there, telling to the public why I could not finish the picture.” I like Rene Daumal, who wrote in the time of the surrealists. He wrote Mount Analogue. It’s not finished, because he died. But all the public read it, even though it wasn’t finished. You can do it.

Even if you don’t shoot a frame, your film might be popular. The new documentary “Jodorowsky’s Dune” demonstrates how your unmade “Dune” project wound up becoming very influential to other films like “Star Wars” and “Alien” and “The Terminator.” It seems as if your film was more powerful because it wasn’t made. Like a ritual sacrifice, almost.

Yes. You put the seed in. A young director named Jan Kounen asked me in Paris, he wanted to make an animation of “Dune.” I said no, because what was fantastic was with Dali, with Orson Welles, with Dalila di Lazzaro—a fantastic Italian actress nobody knows about. You cannot do that picture with animation. Dali animated—what is that? But, I am happy. They steal my scenes, they imitate me. A lot of people took things from me when I made “El Topo.” I felt very good. My ego every day is more and more polite. I tame it. When you’re an artist, your ego is there [raises hand high] and you have to bring it down. The world is more important than you.

Maybe all the difficulties you’ve had making your films has helped you in that regard? If it had been easier for you to make movies, you might not be aware that the world is bigger than you.

If I made “Dune,” I could have been as rich as Spielberg. But maybe I would have sold my soul. But I knew I was in another century with that movie. I wanted a picture of 14 hours. Hollywood thought I was crazy. A 14 hour picture is crazy! But now you can do it, with television series. 20 hours, 30 hours. You can watch these chapters until you are tired.

So you knew it was an impossible project. But you were still very committed to it.

Yes. I fought to find Dali. It was impossible to find him. He asked to be paid $100,000 an hour. I changed the script. I say to him, “I will make a contract for you for one hour.” I will make a hyperrealist model of you. I will make your character, the Emperor of the Galaxy, afraid of everything. I will have him create a double of himself who is a robot. And then I will use the robot. It won’t be Dali. Dali I will only use for one hour. So, for $100,000 I have Dali. I say to Dali, “I will illuminate the whole set. And then wherever you move, I will shoot as I can.” I will have light everywhere, décor will be mobile. Wherever he goes, I will move the décor. And Orson Welles, of course, I find in a restaurant. It was an adventure. I would go to the restaurant, and I would watch him secretly, like a hunter. I would go to the chef or the waiter and ask, “What is he eating? What is he drinking?” I sent him an expensive bottle, and he talked to me.

Filmmaking always seems to be an adventure for you.

Always. When we were shooting this picture, I needed a circus. In Santiago de Chile, they rent me a circus, but it was awful. But I remember, when I was flying into Santiago de Chile, I saw in the town a circus, with colors. I say, “There is a circus somewhere. We have to go to find this circus.” Also, I wanted, in another scene, transvestites. But where will I find transvestites in Santiago de Chile? We spend three hours searching for the circus. Then we see a circus by the side of the road, but it’s against the traffic. We go against the traffic. Rrrrr! [Makes a car screeching sound] And we are at the circus. We need to speak with the person who runs the circus. We go to the door. Who opens the door?

Let me guess. A transvestite.

A transvestite! It was the circus of seven transvestites. So I rent the transvestites, and I rent the circus, and it’s in my picture.

You’ve lived and worked all over the world. Have you ever felt at home anywhere?

Only in my shoes, I like to say. I have no nationality. When my father was five years old, he hid. He didn’t like the name Jodorowsky. He didn’t like any tradition. So, I have no nationality. The Chileans didn’t like me, because I was white, my nose was different. I never had a place for me. But now, everywhere, I feel good. I have no prejudice. Everywhere I go, I am an extraterrestrial.

Today, I went to see Gauguin at the museum. He paints only women. Primitive women. No men. He’s painting the happiness of living in that island. He went there, fucking. He had like a harem. He was happy. For me, he’s not so good a painter; I prefer Picasso. But this is art, in some ways: To discover where you’re happy. I am happy when I am doing a picture. To make a picture, for me, is a way of life. I forget everything, and I live it. You are creating worlds. You get to be a god. I am living in another state of being, like a medium. It’s not me. I don’t remember how I did it. How did I direct a child? I don’t remember. It’s the same when I make poetry, or I make a tweet. You start a thing, and then the thing starts to change you.