Interview with L. Ullmann (1975)

Interview with L. Ullmann (2001)

The solitary, poetic, fearful, creative, brave and philosophical mind of Ingmar Bergman has been stilled, and the director is dead at 89. Death was an event on which he long meditated; it was the subject of many of his greatest films, and provided his most famous single image, a knight playing chess with Death in “The Seventh Seal.”

The end came Monday on the remote island of Faro, off the Swedish coast, where he made his home and workshop for many years. During a long and productive career, he made more than 50 films, some of them in longer versions for television, and directed more than 200 plays and operas.

Woody Allen, who made some films in deliberate imitation of Bergman, said he was “probably the greatest film artist, all things considered, since the invention of the motion picture camera.”

And David Mamet has just written me: “When I was young the World Theatre, in Chicago, staged an all-day Ingmar Bergman Festival. I went at ten o’clock in the morning, and stayed all day. When I left the theater it was still light, but my soul was dark, and I did not sleep for years afterwards.”

Provided with a secure home for decades within the Swedish film industry, working at Stockholm’s Film House, which his films essentially built, Bergman had unparallel freedom to make exactly the films he desired. Occasionally they were comedies, and he made a sunny version of Mozart’s “The Magic Flute,” but more often they were meditations on life and death, on the difficulties of people trying to connect, and on what he considered the silence of God. In a film like “Wild Strawberries (1957), however, he imagined an old man terrified by death, revisiting his memories, and finally finding reconciliation.

The son of a strict Lutheran minister, Bergman remembered such punishments as being locked in a cabinet and told mice would nibble at his toes. He resented his father for years, returning to that childhood again near the end of his career in “Fanny and Alexander” (1982) one of his greatest films.

What he saw as God’s refusal to intervene in the suffering on earth was the subject of his 1961-63 Silence of God Trilogy, “Through a Glass Darkly,” “Winter Light” (a pitiless film in which a clergyman torments himself about the possibility of nuclear annihilation) and “The Silence.” In his masterpiece “Persona,” (1967), an actress (Liv Ullmann) sees a television image of a monk burning himself in Vietnam, and she stops speaking. Sent to a country retreat with a nurse (Bibi Andersson), she works a speechless alchemy on her, leading to a striking image when their two faces seem to blend.

So great was the tension in that film that Bergman made it appear to catch in the projector and burn. Then, from a black screen, the film slowly rebuilt itself, beginning with crude images from the first days of the cinema. These images were suggested by a child’s cinematograph which his brother received as a present; so envious was Ingmar that he traded his brother for it, giving up his precious horde of 100 tin soldiers.

In the fullness of his career, the director settled into a rhythm. “We’ve already discussed the new film the year before,” Sven Nykvist, his longtime cinematographer, told me in 1975. “Then Ingmar goes to his island and writes the screenplay. The next year, we shoot – usually about the fifteenth of April. Usually we are the same eighteen people working with him, year after year, one film a year.”

Of the 18, one was the “hostess,” hired to serve coffee and pastries and make the set seem domestic. “How large a crew do you use?” David Lean asked him one year at Cannes. “I always work with 18 friends,” Bergman said. “That’s funny,” said Lean. “I work with 150 enemies.”

In 1975 I visited the Bergman set for “Face to Face.” He took a break and invited me to his “cell” in Film House: A small, narrow room, filled with an army cot, a desk, two chairs, and on the desk an apple and a bar of chocolate. He said he’d been watching an interview with Antonioni the night before: “I hardly heard what he said. I could not take my attention away from his face. For me, the human face is the most important subject of the cinema.”

Nykvist was his collaborator in filming those faces, and in “The Passion of Anna” (1969) did something unprecedented: Filmed a conversation by the light of a single candle. “He said it could be done, and he was right,” Bergman said.

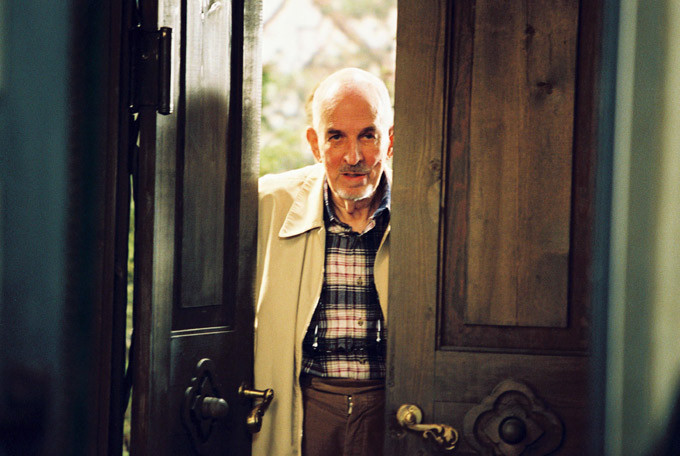

Bergman was married five times and had eight children, including Liv Ullmann’s daughter, the novelist Linn. He was not proud of how he behaved in some of those relationships, and in an extraordinary late film, “Faithless” (2000), written by Bergman and directed by Ullmann, he imagines a director (Erland Josephson) hiring an actress (Lena Endre) to help him “think through” an unhappy affair. It becomes clear that the actress is imaginary, that the affair has some connection with Ullmann and other women, and that the film is a confession. It is all shot on Faro, in Bergman’s house.

Other filmmakers spoke in awe of Bergman’s methods, which had the luxury of time an complete independence. Haskell Wexler, the great cinematographer, has just written me: “I was good friends with Sven Nykvist, who told me stories about Bergman. They sat in a big old church from very early in the morning until as black as the night gets. They noted where the light moved through the stained glass windows. Bergman planned where he would stage the scenes for a picture they were about to do. This had the practical advantage of minimizing light and generator costs. Sven said sitting alone with Ingmar in the church had a profound effect on him. I asked him if it made him more religious. He said he didn’t think so but it did give him some kind of spiritual connection to Ingmar which helped him deal with the times Bergman became very mean…”

There are so many memories crowding in, now, from the richness of Bergman’s work, that I know not what to choose. A turning point in his despair occurred, perhaps, in “Cries and Whispers,” a chamber drama in an isolated Swedish estate where Harriet Andersson is dying painfully of cancer and her sisters have come to be with her. After she dies,they find a journal in which she recalls a perfect day in the autumn, when the pain was not so bad, and the women took up their parasols and walked in the garden. “This is happiness. I cannot wish for anything better,” she writes. “I feel profoundly grateful to my life, which gives me so much.”

When “Faithless” played at Cannes in 2001, Liv Ullmann told me this story:

“When he was 60 years old he celebrated his birthday on his island, on that beach. And my daughter was there; she was five years old. And…he said to her, ‘When you are 60 what will you do then?’ She said, ‘I’ll have a big party and my mother will be there. She’ll be really old and stupid and gawky but it’s gonna be great.’ And he looked at her and said, ‘And what about me? Will I not be there?’ And the five-year-old looked up at him and she said, ‘Well, you know, I’ll leave the party and I’ll walk down to the beach and there on the waves you will come dancing towards me’.”

The Great Movies section of rogerebert.com includes “Persona,” “The Seventh Seal,” “Cries and Whispers” and “Fanny and Alexander.” Some of Bergman’s greatest scenes, including the chess game and the merging faces, are at blogs.guardian.co.uk/film/2007/07/ingmar_bergmans_greatest_scene.html