At 8:20 p.m., the body artist Chris Burden entered a large gallery of the Museum of Contemporary Art, did not look at his audience of 400 or more, set a clock for midnight, and lay down on the floor beneath a large sheet of plate glass that was angled against the wall.

So began on April 11 a deceptively simple piece of conceptual art that would eventually involve the imaginations of thousands of Chicagoans who had never heard of Burden, would cause the museum to fear for Burden’s life, and would end at a time and in a way that Burden did not remotely anticipate.

The piece began, in a sense, a month earlier, when I was interviewing Burden at the Arts Club of Chicago in the company of Ira Licht, the museum’s curator. At that time Burden had just completed a piece in a New York art gallery that involved his living for three weeks on a triangular platform set so high against one of the gallery’s walls that no one could see for sure if he was really up there. He took no nourishment except celery juice.

The piece had been spooky, mystical, Burden was saying. There had been something infuriating, for some of the visitors to the gallery, in the notion that a human presence was up there in the shadows under the ceiling, not speaking, not doing anything, just waiting.

Some of the visitors tried to take running jumps up the wall in an attempt to see Burden, or a hand, or a shoe, or a couple of eyeballs in the darkness. Others took it on trust that he was there. Burden heard one young man telling his friend that the feeling in the gallery was almost spiritual: “He can hear us, and he doesn’t answer, but he can’t help listening…it’s like God.”

Burden had been invited to Chicago to participate in an exhibition of “conceptual art” at the museum. Earlier that morning, he’d visited the gallery where he’d be performing, and now at lunch he said he wasn’t sure yet what he would do, but he had a few ideas.

Would it be fair, Ira Licht asked, to ask for some rough estimate of how long the piece might last?

No, Burden said, it wouldn’t. A piece lasting 45 seconds might be richer than one lasting two hours.

Licht said there might be a problem if some of the museum’s members arrived a few minutes late and the piece was already over. Well, Burden sighed, he couldn’t please all of the people all of the time. And it was at that moment that the idea for his April 11 performance came to him…

The talk at the luncheon moved on to some of Burden’s earlier pieces, and inevitably to the performance by which he earned his master’s thesis at the University of California at Irvine: He had himself locked into a locker measuring 2-by-3-by-3 feet for five days; there was a five-galloon jug of water in the locker above him and, with admirable logic, an empty five-gallon container in the locker below him. Word of the piece had spread all over the campus, and hundreds of students had come to talk to him through the locker’s grillwork. One of the beauties of the piece, Burden said, was that, of course, he had to listen: “I was a box with ears and a voice.”

On another occasion, Burden had himself manacled with brass rings to a concrete floor, flanked by two buckets of water with live electric wires in them. The audience was admitted, and trusted not to knock over a bucket and electrocute the artist. “I had absolute faith that they wouldn’t,” Burden said. “After all…I’m not suicidal.”

For other works Burden had himself nailed to the roof of a Volkswagen, and shot in the arm with a rifle (“It was supposed to be a graze wound, but the marksman missed”). These more violent pieces tended to attract more attention, he said, but some of his quieter pieces were perhaps more interesting. The idea in conceptual art is that the artist causes experiences to happen to himself, and then ruminates on the interaction between the self and the experience; an audience may be permitted to observe, but is not essential.

When he returned to Chicago in April, Burden told the museum he would require the large industrial-style clock, the sheet of plate glass, and nothing else. The clock was fastened to the wall and the sheet glass was leaning against it at a 45-degree angle when the museum’s doors were opened at 8 p.m.

An unusually large crowd filed in, attracted perhaps by publicity about Burden’s previous performances. There was a slight carnival atmosphere. The tone was muted somewhat because of a large number of spectators who were seriously interested in body art, but all the same a definite feeling existed in the room that some people had come to see blood.

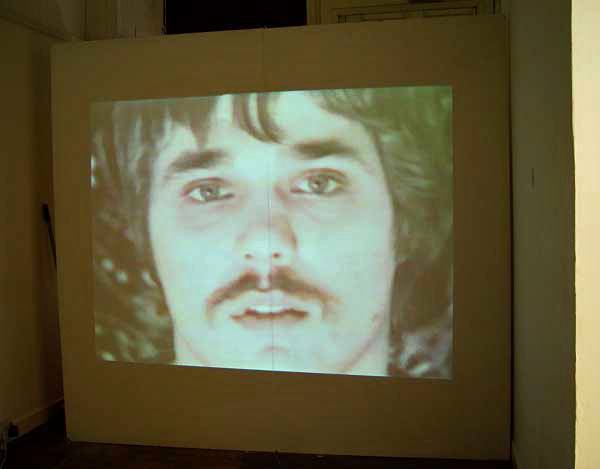

At 8:20, Burden entered the gallery, set the clock for midnight and laid down under the glass. He was wearing a Navy blue sweater and pants, and jogging shoes. He let his hands rest easily at his sides and looked up at the ceiling, blinking occasionally. He could not see the clock.

The audience perhaps expected more. There was a pregnant period of silence, about 10 minutes, and when at the end of it nothing else had happened, there were a few loud whistles and sporadic outbursts of clapping. Burden did not react. At various times during the next two hours, audience members tried to approach Burden with advice, greetings, exhortations, and a red carnation. They were politely but firmly kept away by the museum attendants. A girl threw her brassiere at the glass; it was taken away by a smiling guard.

At 10:30 p.m., when I left, the crowd had dwindled down to perhaps 100. I came back to the Sun-Times to write a mildly quizzical article, and then called Alene Valkanas, the museum’s publicist, to ask if Burden was still on the floor.

“Yes, he is,” she said. “It’s a really strange scene here right now. There are about 40 people left, and they’re all very quiet. Burden doesn’t move. It was more like a circus before; but now it’s more like a shrine…very mysterious and beautiful.”

I filed the story with a pre-written editor’s note: “At (fill in the time and day), Chris Burden ended his self-imposed vigil.” The editor’s note was never to run.

I left to meet friends for a drink, and we talked about Burden and what he was up to. There was the suggestion that this was another of his danger pieces, that eventually someone would become impatient enough to throw something at the plate glass and break it, that Burden’s immobility was an impudent invitation of violence toward himself. Nobody had a better idea.

The room was crowded and happy and noisy, but I felt my thoughts being pulled back to that vast, empty gallery with the sheet glass leaning against one wall. At 1:15 a.m., I went to the pay telephone and called Alene. She said Burden was still on the floor. I said the hell with it and drove back downtown to the museum. Burden had not moved.

Two of the museum guards still remained (one of them, Herman Peoples, would become so involved in the piece that he would voluntarily share the vigil with Burden, vowing not to leave until it was over). There was a television reporter, Rich Samuels of WMAQ, sitting on a mat of foam rubber, and a young couple who left soon after I arrived. Two banks of spotlights illuminated Burden against the wall, and the other lights had been turned out; a zaftig nude by Gaston Lachaise lounged in the shadows.

“He doesn’t move except for what look like isometric flexings,” Alene Valkanas said “He flexes his fingers sometimes, and once in a while you can see his toes flexing.”

Burden seemed removed to a great distance. He was not asleep. There was no way to tell if he was in a meditative trance, or had hypnotized himself, or was fully aware of his surroundings. After an hour, I left very quietly, as if from a church.

The next day I’d planned to drive down to Urbana, but before I left I called the museum. It was noon; Burden had still not moved, the museum said. Fifteen hours and 40 minutes.

During the drive downstate, my thoughts kept returning to him, and I wondered what he was thinking and how he felt, and if he were thirsty, and if he had to piss. The radio stations had picked up on the piece by now, and were inserting progress reports on their newscast. Disc jockeys were finding the whole thing hilarious.

On Sunday, driving back to Chicago, I stopped at the Standard Oil truck stop in Gilman to call the museum. Burden had not moved. The time was 2:30 p.m. Forty-two hours and ten minutes. I came into the office, where I learned that Ira Licht and other museum authorities were consulting specialists to determine whether Burden’s life was in danger. A urologist said no one could go more than perhaps 48 hours without urinating and not risk uremic poisoning. Burden hadn’t had anything to drink, but that was not a problem at the moment, apparently; since he was not exercising he would not dehydrate dangerously in only two days.

Alene Valkanas called at a little before 6 p.m.

“The piece ended at 5:20,” she said. Forty-five hours. “We felt a moral obligation not to interfere with Burden’s intentions, but we felt we couldn’t stand by and allow him to do serious physical harm to himself. There was a possibility he was in such a deep trance that he didn’t have control over his will. We decided to place a pitcher of water next to his head and see if he would drink from it. The moment we put the water down, Chris got up, walked into the next room, returned with a hammer and an envelope, and smashed the clock, stopping it.”

The envelope, sealed, contained Burden’s explanation of the piece. It consisted, he had written, of three elements: The clock, the glass, and himself. The piece would continue, he said, until the museum staff acted on one of the three elements. By providing the pitcher of water, they had done so.

“I was prepared to lie in this position indefinitely,” he continued. “The responsibility for ending the piece rested with the museum staff but they were always unaware of this crucial aspect.” The piece had been titled “Doomed.”

The idea for the piece, Burden explained later, had come during our lunch with Licht: “I thought, if he’s concerned about how long the piece will be, I’ll do a piece in which he has complete control over the length.”

“My God,” Alene Valkanas said. “All we had to do was end it ourselves, and we thought the rules of the piece required us to do nothing.”

During the 45 hours, Burden had been in psychological danger, perhaps, but not in physical danger; he had urinated, but the museum staff had not noted the signs on his navy-blue dungarees. He had been thirsty and hungry, Burden said, and he had been completely conscious at all times except for some fleeting periods of sleep. He had not used a self-imposed trance, or yoga, or anything else except self-discipline to keep himself lying there.

“I thought perhaps the piece would last several hours,” Burden said. “I thought maybe they’d come up and say, okay, Chris, it’s 2 a.m. and everybody’s gone home and the guards are on overtime and we have to close up. That would have ended the piece, and I would have broken the clock, recording the elapsed time.

“On the first night, when I realized they weren’t going to stop the piece, I was pleased and impressed that they had placed the integrity of the piece ahead of the institutional requirements of the museum.

“On the second night, I thought, my God, don’t they care anything at all about me? Are they going to leave me here to die?”