He introduces himself in English: “My name is Tatsuya Nakadai.” He may be 83 years old now, but the star of “Sword of Doom,” “Ran,” “Kagemusha,” “The Human Condition,” “The Face of Another” and many more is unmistakable. Those piercing eyes alone! He speaks eloquently about his past in a mannered basso voice, everything from his time working in the Shingeki theater company to co-starring with samurai movie icon Toshiro Mifune in genre milestones like “Yojimbo” and “Sanjuro.”

We often unknowingly condescend to our elders by saying that they are “very lucid for their age,” but when Nakadai speaks, he delivers thorough history lesson that are not limited to personal anecdotes. He is electrifying, a living legend whose presence at Museum of the Moving Image’s 50th anniversary screening of “Sword of Doom” made the event one of the highlights of the New York repertory calendar. RogerEbert.com spoke with Nakadai on Saturday about swordplay, nostalgia, and becoming a small mountain of snow for your art.

The climax of “Sword of Doom” is so chilling and it’s all carried by your energy and stamina. This was a hard film for you to shoot. Can you recall what shooting this climactic final scene was like?

“Sword of Doom” was shot in 1966, when I was 33 years old. It was directed by the great Kihachi Okamoto. He and I made several films together. He’s known for making comedies with a light touch … happy films. But “Sword of Doom” is, of course, a tragedy. The film was based on a very famous novel in Japan. It was adapted to film three times; ours was the last adaptation. It was written by an author named Kaizan Nakazato. He was actually a newspaper reporter for Hochi Shimbun. His story, “Sword of Doom,” was serialized over the course of three years.

In the film, [my character] Ryunosuke commits a murder without a reason. But in Japan, there’s the concept of reincarnation in Buddhism. So if you commit a sin, it will be passed on to the next generation. So Ryunosuke is this man who uses this crazed, almost cursed sword. But when it comes down to it, the film is very much a “chanbara,” or samurai-swordplay film. As you said, in the last scene, I slashed down about 70 people in a period of three days. So I myself had lost my mind as well. That’s how I felt.

“The Human Condition” was a major breakthrough for you and your career. How did that film’s success affect you?

I started shooting “The Human Condition” when I was 24. It took four years to film, and by the time it was completed, I was 28. The role in “The Human Condition” is very serious. It’s very much an anti-WWII film, very much against the Japanese Imperialist army. So in that sense, it’s a very different role than Ryunosuke in “Sword of Doom.” But, having filmed “The Human Condition” over the course of four years, I would say that it’s a work that’s very representative of my 20s. People often ask me: Kaji—the role in “The Human Condition”—or Ryunosuke in “Sword of Doom,” which one do I like? But they represent a stark contrast between good and evil. So I would have to say I love them both.

You would frequently do your own stuntwork when working in the films of Masaki Kobayashi. Sometimes, this wound up getting you hurt, or sick, like when you got hypothermia working on “The Human Condition.” Is there a part of you that enjoyed—or maybe still enjoys—an immersive experience of working with real weapons, doing your own stunt work … a very hands-on process?

Director Kobayashi was quite a severe filmmaker. In the very last scene in Junpei Gomikawa’s source novel, Kaji literally becomes a small mountain of snow. Director Kobayashi, when he took upon that scene, said “I literally need Nakadai to become a small mountain of snow.” So I endured hypothermia on a small Northern island until I literally became a small mountain of snow.

You were not signed exclusively to work with any one studio. How did that affect the way you chose your roles?

My career spans about 60 years. I’m now 83, and still very active as an actor. I can only speak from my experience, but I come from a theatrical background. I worked with an acting school for about three years before I joined a theater troupe, and I continue to work at the theater troupe. So at the time, there were about five influential film studios in Japan. I didn’t join any contracts with any film studios; I was very much a free agent. But the reason I did that was: if I joined a contract with any particular film studio, it restricted me to film, and I wouldn’t be able to do any theater. So at the time, I was a freelancer. This allowed me to be invited to very different, diverse projects from a variety of filmmakers.

Talk about the people you worked with at the Shingeki theater, your favorite plays, and how these works influenced your work on movies.

I want to talk a little about why I chose to work simultaneously in the Shingeki theater and film. When I was younger, I split my year in half: the first half of my year I would devote to film, and the latter half I would devote to theater at Shingeki. At the time, there were three very influential troupes in the Shingeki theater, one was Haiyu-za, which I belong to, and the others being Bungaku-za, and Mingei. My teacher there was Korea Senda. Did you see the exhibit on the Noh theater at Japan Society?

Yes!

One of the choreographers is Michio Ito, the younger brother of Koreya, my teacher for twenty years. Koreya devoted himself to theater while Ito was one of the choreographers.

You were friendly with Toshiro Mifune, though you usually played enemies on screen. What was your working relationship with him like? Did you ever compare your performance to his?

My first role with Mr. Mifune was in “Yojimbo,” I believe. I played the role of the sliced-up actor. The next time was in “Sanjuro,” where once again, at the very end, blood just gushes out of me. We also were cast together in Kurosawa’s “High and Low,” so I would consider Mr. Mifune my most respected “senpai” [superior, or elder]. He’s also in “Sword of Doom.” His chanbara—his swordplay—is astounding. I would always work hard on my swordplay, just so I could catch up with him. I would consider him my great mentor, and inspiration.

You once said that samurai movies are popular in Japan because they cater to viewers’ sentimentality and nostalgia. What do you think about the genre, as an actor, someone who lived and performed as samurai characters? Do you enjoy these types of films?

I started making samurai films when I was 29, in “Harakiri.” In Japan, the bushido, or the code of the samurai, is the foundation of Japanese aestheticism, and the way of life for Japanese people. But for [“Harakiri” director] Masaki Kobayashi, he really depicted the lie and superficiality of bushido, as well as the cruelty of the samurai. In that sense, it was an antidote. He really depicted the struggle between the individual and society. So for me, I view the samurai film genre as a form of entertainment. But at the same time, it’s an antidote to what’s going on in modern society and politics.

You also starred in “Kill,” which makes fun of the samurai movie’s conventions. Are there any tropes of the samurai genre that you are either very fond of or really hate?

“Kill” is a very different film than “Harakiri.” It’s a sort of action-comedy, and it’s also critical of the samurai way. As far as what I like about the samurai films: taking on the roles of older people, people who lived hundreds of years ago. That really intrigues me. Also, chanbara, the swordplay. I consider it a sort of sport. Whenever I go around the world, people are always interested in chanbara. But for me, I’m very interested in performing chanbara because it’s almost like a dance. I’m always intrigued how people around the world are interested in, or know about chanbara. But for me, the chanbara genre and the “jidaegeki,” or period film, go hand-in-hand. You can’t have one without the other. As far as chanbara, it’s still a very difficult art form.

At the same time, in post-war Japan, we were awe-struck by the American western, and the quick blasting of pistols. It’s sort of the same effect as chanbara swordplay. There’s an element of performance that makes films so intriguing and attractive.

Are there any particular roles or films you’ve been in that didn’t catch on that you wish had?

I’ve been in a lot of masterpieces! I shot “Sword of Doom” 50 years ago when I was 33. In that sense, a good quality of film really transcends time and space, and endures. For instance, I watch a lot of older films, like Elia Kazan’s “On the Waterfront.”

Is “Harakiri” still the role you are most proud of?

I’m a Japanese actor, and have been in over 160 films over a career of 60 years. Saying that is kind of embarrassing for me. That might be too many. It’s interesting because films that were critically panned sometimes really stick in my memory. “Age of Assassins,” for instance, was panned, but nowadays it’s accepted in this contemporary perspective. But in regards to direction, screenplay, lighting, cinematography, and all my co-stars? Comprehensively speaking, “Harakiri” is the one that will stick with me, and that I will remember on my deathbed as I pass on.

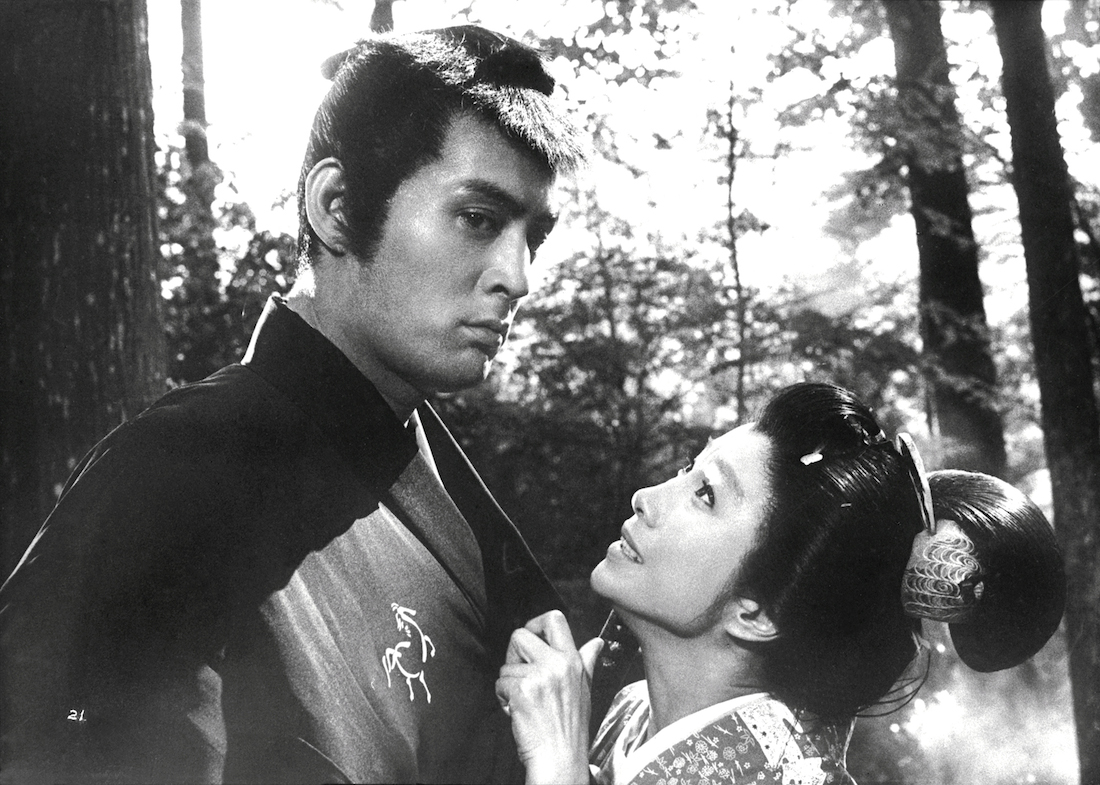

Image credit to @1966 Toho Inc, Ltd.