My first virtual dispatch from the largely online Venice Film Festival was a remarkable 3-for-3 with the excellent “Dear Comrades” anchoring the feature alongside two other solid films. My second and final (most of our fest coverage this year will run out of Toronto) is less consistent with a trio of films that all frustrated me to varying degrees. Still, it’s nice to analyze such distinctly different works from around the world. It’s what I miss the most about the festival experience—the variety of voices being elevated on the same platform.

The best of the three in this follow-up is Hilal Baydarov’s hypnotic “In Between Dying,” a dreamlike experience co-produced by Carlos Reygadas (“Post Tenebras Lux”). Even with the description in the official Venice program, “In Between Dying” defies traditional plot summary analysis. It is a film filled with long, poetic shots of the Azerbaijani landscape that work together to create an overall mood more than an easily accessible story. It can feel a bit too purposefully obtuse at times, but its mood grew on me and Baydarov has an impressive eye, finding lyricism in relatively mundane landscapes.

Davud (Orkhan Iskandarli) is a young man seeking meaning and function in his life. Told mostly through very long shots in which Davud is really a figure on a broad canvas of the desolate landscape of where he lives, his restlessness keeps him moving through a very strange day. He has a series of encounters, most of which end in death, and a car full of other men ends up tracking him. Themes start to emerge in these encounters, including the subjugation of women and the sense that Davud is a disruptive force in traditional lives.

Baydarov’s Venice debut was apparently largely improvised and inspired by the story of the Buddha, the tale of a young Siddhartha who traveled from his family home and discovered the pain and suffering in the world. The director’s approach is emotionally driven, telling Variety that he finds inspiration from filmmakers like Robert Bresson, Ingmar Bergman, and Andrey Tarkovsky. These influences are clear while watching “In Between Dying,” a film that felt too distant for me at first but started to work on another register. Baydarov tells Variety, “I’d rather people feel a film before understanding it.” I’m not sure I’ll ever understand all of “In Between Dying.” But I definitely felt it.

Another film seeking an emotional response is one that was set to premiere at SXSW and won an award there virtually, which now travels from Austin to Venice. Logan George and Celine Held’s “Topside” tells a tragically realistic story of a homeless mother and her daughter who live in the tunnels below New York City and struggle to find their way back to what they call home after their life is disrupted. Everyone here means well, and there’s a commitment to the entire venture that’s admirable, but this falls deep into what is often referred to as “poverty porn,” something that feels more manipulative in its depiction of misery than genuinely empathetic or artistic. Yes, there are stories like this taking place every day in major cities, but the impact feels cheaper because of the way it places so much narrative weight on the danger of a five-year-old’s existence. Putting kids in this kind of jeopardy has inherent emotional power that will work for some viewers, and I get that, but I felt throughout like my buttons were being pushed, and that never allowed me to lose myself in this story emotionally. Move me, don’t manipulate me.

Nikki (co-director Held) lives in the tunnels under Manhattan with her daughter Little (a natural Zhaila Farmer). After a raid, they’re forced to the surface, where Nikki struggles through the night trying to find a place for them to stay before trying to find their way back to the underground community when it’s safe again. It leads the pair into the den of a dealer played charismatically by Jared Abrahamson and through a city that feels even more dangerous than the one underground.

There are genuine, grounded performances throughout “Topside” that clearly emerge from a cast and crew willing to look at people who are often ignored in society. That’s admirable, for sure, but there’s still a sense that this is a story told by outsiders in a manner that lacks lived-in depth. Most of all, putting a young child in mortal danger by sending her through a wintry night with a woman who may not be capable of ensuring her safety has undeniable power but it just pushed too hard into exploitation for this viewer. Yes, there are duos like Nikki & Little struggling on the edge of society right now. But just seeing them isn’t enough and “Topside” never quite asks the deep questions about why that is.

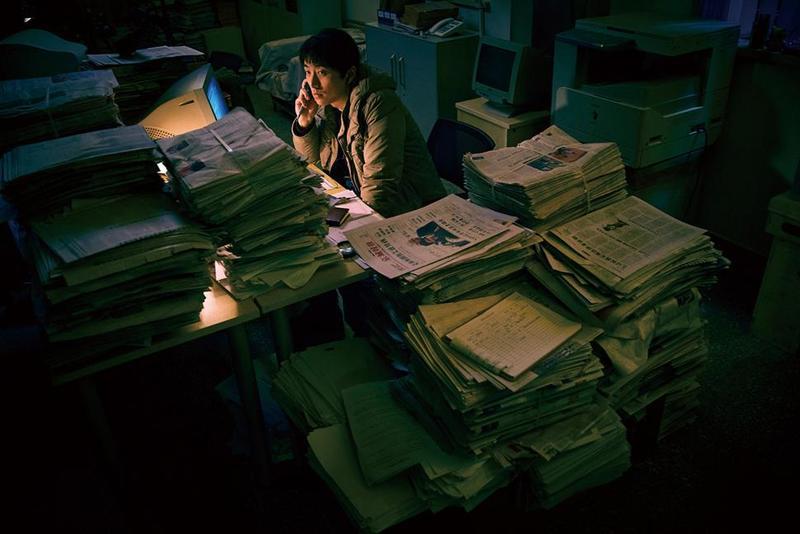

My final Venice film tells a story from the other side of the world but Jing Wang’s “The Best is Yet to Come” has a similar disappointing energy in which just telling an untold chapter of world history doesn’t inherently make for good art. Working with the great auteur Jia Zhang-ke, Jing Wang has made a film from the “heroic journalist” subgenre, one that charts the trajectory of a young writer who discovers that the story that’s going to change his life isn’t as simple as he first presumes it to be. I’m a sucker for a film that elevates the importance of journalism, especially in a country that places the restrictions on it that China does, but this is relatively generic filmmaking, a movie that never elevates above the details of what really happened to transform reality into art.

Han Dong is a young journalist who never even graduated middle school but is convinced that his skills with “keen observation” can make him into a reporter. He ends up talking his way into an internship at one of Beijing’s biggest newspapers and ends up working on a major story early in his career, assisting a piece about a cover-up of a mine disaster. Feeling the high of an expose, Han Dong quickly moves onto a story of medical fraud, people forging tests for Hepatitis-B, which kept those afflicted with the disease from getting work or going to school for generations. At first, Han Dong thinks that the piece he’s writing is about the illegal operation that creates fake medical reports, but he quickly discovers that the real story here is the need for such an underground system.

“The Best is Yet to Come” often comes across too literal in its dialogue and narrative structure. Han Dong literally says, “What we write doesn’t change anything,” and anyone who’s ever seen a movie knows what will follow will refute his cynicism. Again, this is a noble piece of filmmaking that’s intended to highlight an underreported story, but Jing Wang’s approach is as subtle as a newsmagazine show, lacking in subtlety and nuance.

Brian Tallerico is the Managing Editor of RogerEbert.com, and also covers television, film, Blu-ray, and video games. He is also a writer for Vulture, The Playlist, The New York Times, and GQ, and the President of the Chicago Film Critics Association.