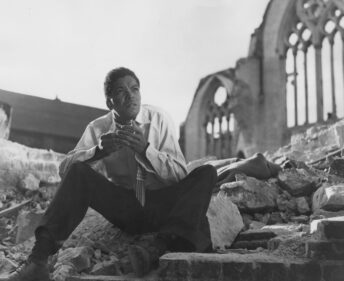

Don Cheadle has threatened to play Miles Davis for what feels like all of my twenties, and I’ve waited patiently because it just made sense. But what would this artist, who clearly felt some kind of intense connection towards the most gigantic figure in jazz music, bring to Davis’ life?

In the final product, “Miles Ahead” (which Cheadle also directed), there’s his lead performance as Davis—absolutely electric, truly inhabiting the man and his icy swagger. There’s the treatment of his music, moving past respectful into an almost collaborative relationship with the way it moves, and the feelings each note inspires. And there’s Cheadle’s direction, the most impressively free of all. Cheadle’s images have a smoky translucence (all the better to capture a man who seemed to exhale cigarette smoke more than carbon monoxide) that allow for mood swings and temporal shifts, to follow Davis’ life from one improvised passage to the next. He’s said he wanted to make a movie he thought Davis would like to star in. Davis had bizarre taste (like with his late ’80s material) so this may be true—but more importantly, Cheadle’s directed a movie he believes in, and you can feel it in every image. The issue is that he’s imposed a structure on his movie that his craft rejects. He directed a great movie of a so-so idea for a story.

Miles Ahead follows Davis through a fictionalized day in his life before his comeback in the late ’70s. He uses a slimy reporter (Ewan McGregor) as his chauffeur as he tracks down money and a stolen recording. Meanwhile everything Davis sees or hears takes him back to a different point in his career, usually based around his relationship with wife Francis Taylor (Emayatzy Corinealdi), the dancer whose face mocks him from the cover of “Someday My Prince Will Come.” In one sense this day-in-the-life structure works just fine, in that it gives momentum to what could have been boringly chronological (the world doesn’t need another “Ray”), but it also keeps Cheadle from embracing the grainy delight he takes in capturing Davis’ essence. Each of these vignettes, from recording sessions to a bloody arrest, dazzle in their fury and intimacy, but there remains throughout the unfortunate nagging question of where they’ll lead. And sure enough, the film has no ending worthy of its best moments. It wants to stop and leave you with the urge to go put on his albums and rediscover him all over again—which is a nice impulse that sort of betrays the work. But that wouldn’t be such a problem if the film preceding the weak close weren’t so alive.

Cheadle is working in a mode that channels the best of LA’s black filmmakers. The shaggy-dog journey in the first story most directly recalls Charles Burnett’s “When It Rains” about a musician on a quixotic jaunt through his neighborhood. And Cheadle’s pumping action beats like a car chase; a gunfight and a basement brawl feels like a pean to Melvin Van Peebles, whose celluloid has a similar hazy transience. It’s dirty, thrilling, raw and feels like a low-budget movie, and that is nothing to shrug at. To make a film about one of the most famous figures in music full-stop that feels like a home-made passion project, the kind of thing that Burnett and his LA Rebellion cohorts used to make, is quite something. Cheadle’s fidelity to Davis is not just in his marvelously funny and uncompromisingly honest portrayal (he says “motherfucker” better and more frequently than Samuel L. Jackson), but in allowing his filmmaking to have the kind of freedom that used to drive Davis’ music. Take away the flashbacks and this film could easily have played the bottom half of double bills with Gordon Parks’ “Leadbelly” back in 1976. It’s a wild burst of energy powered by an abiding love and respect for its many beautiful black faces and bodies. Unfortunately, Cheadle is beholden to a modern conceit—that the film has to be about what happened to Davis. The movie’s drug-and-booze-fueled heart doesn’t need convention weighing it down.

Cheadle’s gifts as a filmmaker are myriad. He has a good sense of pace and a knack for montage—constructing jumps in time that snap like a snare drum, like a jump through several months using only Polaroids scattered around a bedroom. He can visualize internal drama splendidly—a jazz band in a boxing ring the most arresting of his many marvelous devices. And just by deciding on an alternately presentational and metaphorical approach to such a well-known (if misunderstood) subject, he’s proven an honest and intuitive dramatist. And because of these virtues and despite its few issues, “Miles Ahead” is a hell of a great time. It makes you grateful there are people willing to follow their muse, to take their time and do work that respects the complexities of their subject.

When the screening of “Miles Ahead” finished I walked to a sandwich shop around the corner from the Walter Reade theatre. While I waited for my order, the Steve Miller Band’s “Abracadabra” started playing on the radio. Thank god for artists willing to take chances. Imagine if antiseptic crowd-pleasing radio rock and boilerplate biopics were our only option. The world needs more artists like Davis and Cheadle—people willing to take chances.