In contemporary Hollywood, when a young actor becomes successful, he immediately tries to convert fame into power and money, investing his time in formulaic projects that guarantee great results at the box office and, thus, his ascension in the industry. It was not always like this - and we just need to observe Al Pacino's career to confirm that: after he became a hit with "The Godfather," dozens of screenplays fell onto his lap, but he still focused on challenging and complex works in which he struggled against Hollywood's attempts to turn him into a heartthrob - projects such as "Dog Day Afternoon" (in which he robbed a bank to pay for the sex reassignment surgery of his boyfriend, played by Chris Sarandon) and, of course, Serpico.

In contemporary Hollywood, when a young actor becomes successful, he immediately tries to convert fame into power and money, investing his time in formulaic projects that guarantee great results at the box office and, thus, his ascension in the industry. It was not always like this - and we just need to observe Al Pacino's career to confirm that: after he became a hit with "The Godfather," dozens of screenplays fell onto his lap, but he still focused on challenging and complex works in which he struggled against Hollywood's attempts to turn him into a heartthrob - projects such as "Dog Day Afternoon" (in which he robbed a bank to pay for the sex reassignment surgery of his boyfriend, played by Chris Sarandon) and, of course, Serpico.

Inspired by the real story of New-Yorker cop Frank Serpico captured in the book by Peter Maas, the screenplay by Waldo Salt (Midnight Cowboy, Coming Home) and Norman Wexler (Saturday Night Fever) anticipates in 20 years the introduction of another spectacular work by Al Pacino, Carlito's Way, also presenting his character when he is being taken to the hospital after being shot. Sporting a disheveled beard and wearing a lot of jewelry, Serpico looks like a hippie, so it is with some surprise that we notice that he is a policeman wounded during a mission. The most intriguing aspect of the incident, however, is witnessing the commotion caused by the news of his hospitalization: why, after all, that bearded cop is so important? And why so many of his workmates seem to be so pleased with the possibility of seeing him dead? The sad answer is revealed during a dialogue that presents an apparent paradox: "Who can trust a cop who doesn't take money?", someone asks.

From then on, a long flashback starts to explain the circumstances that led to the attack against Serpico's life, beginning with his graduation in Police Academy: a principled and idealistic young man, he observes with concern the ethical concessions made by his colleagues in uniform in exchange for small favors, like allowing parking in double row in front of a restaurant that doesn't charge for lunch provided to police. Feeling equally uncomfortable with his coworkers' violent methods, he requests a transfer to another district, always hoping to find more righteous partners, but his hopes are quickly dashed when, during his first day in a new police station, someone gives him an envelope containing the bribery of the week.

Illustrating in an anguishing way the dilemma experienced by the title character, the movie approaches corruption like something endemic that, more than acceptable to everybody, is practically imposed by the city's police: divided between the will to change the system and his repulse of becoming a snitcher, Serpico tries to ignore the problem and even forces himself to understand the attitude of his colleagues, as many of them have families and don't earn enough to uphold the Law, ending up accepting money in order to complement their incomes. However, this leads him to be seen with suspicion by his workmates, putting Serpico in a delicate position: after all, all his partners have to do is to not show up in a moment of danger in order for him to become one more fatal victim of the fight against crime.

Exhibiting the security and intense scene presence already seen in Panic in the Needle Park and The Godfather, his two great previous works (before that, he debuted with an appearance in "Me, Natalie," in 1969), Al Pacino demonstrates intelligence by creating a huge contrast between Serpico's future anguish and the irreverent and breezy way he appears during the scenes shortly after graduating as an agent of the Law - and it is moving to realize that the same boy with the cap turned backwards and who insists in answering even the calls outside his jurisdiction will end up giving way to a tense and bitter man that mistrusts everything and everyone, becoming nervous and absolutely intractable.

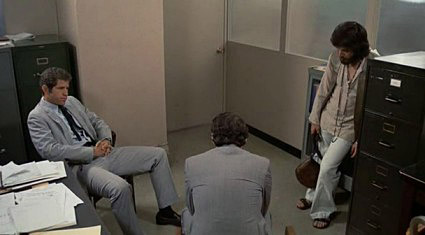

Also, the influence of Method acting preached by Lee Strasberg (of whom Pacino was a student and with whom he would work in "The Godfather, Part II") and consecrated by Marlon Brando can be noticed in brilliant subtleties in the actor's performance, like when he's playing with a rubber band while chatting with a friend (remember Brando picking up Eva Marie Saint's glove in "On the Waterfront"), when washing a bowl before using it to give water to a dog or even by keeping focused in character during the scene in which he almost falls when trying to sit down. Likewise, by portraying Serpico as a calm man most of the time, Pacino creates, by contrast, more impact in the moments he explodes - like in the brilliant scene in which, after arresting a man protected by his district's colleagues, the hero finally loses serenity when he realizes that nobody takes the crime seriously (and Sidney Lumet's decision of shooting the scene in a long, full shot, is fabulous, since it allows us to witness the increasing discomfort of all detectives as Serpico becomes more and more nervous).

But Frank Serpico is more than a cop: differently of many movies that define their characters by their professions, here the protagonist demonstrates other interests besides trying to "solve the case and arrest the bad guy": a product of a period of intense cultural agitation (the end of the 60's and beginning of the 70's), Serpico is interested in art and tries to establish contact with people from different areas of interest, showing his attunement with his time even through his appearance (and growing his mustache and his hair even helps him as a disguise - a win-win situation). By the way, it's fascinating to realize the difference of the approach between Serpico (which embraces the hippie culture and its intellectual curiosity) and the fascist McQ, directed by John Sturges just the following year (1974) and which presented John Wayne as a detective that also faced police corruption, but who had a real contempt for the hairy young boys of his time (by the way, it's a pity that Sturges and Wayne's only collaboration is so stupid).

But Pacino is not the only highlight of the cast: taking a role that's usually ungrateful - the hero's girlfriend -, Barbara Eda-Young turns Laurie into a three-dimensional character by showing her dedication to Serpico, but also her increasing frustration after seeing him become obsessed by his professional problems. Yes, she loves him, but also finds it hard to live with someone who is always about to have a nervous breakdown (who wouldn't?) - and that makes her feel an even more uncomfortable guilt (which also proves her dedication to him). Meanwhile, John Randolph performs the feat of inspiring confidence in the viewer as soon as he appears - something hard to accomplish in a movie full of traitors and corruption (and more interesting is that he does that by playing the character as a grumpy man who seems to communicate only by screaming). And if Judd Hirsch, F. Murray Abraham and M. Emmet Walsh all appear in small parts, the great Tony Roberts uses the pragmatism of his Bob Blair as an important counterpoint to Serpico's impetuosity.

A director relatively undervalued considering his huge contribution to Cinema, Sidney Lumet gives verisimilitude to the narrative through details like the cop who writes down a car's plate that was hit accidentally during a shootout and Serpico's care when filling the reports of the arrests he makes. Moreover, the filmmaker illustrates the sense of isolation of the protagonist by focusing him in wide shots that make him small before the world and also establish the urgency of his situation by including threatening close-ups of the detectives that surround him in the park. In another moment, Lumet uses specific lenses to flatten the image, voiding the perspective of depth and making the scenario "grow" over Serpico - and the result is clearly oppressive.

By the way, the editing of now legendary Dede Allen (who helped to revolutionize the medium's narrative language a few years before, in "Bonnie and Clyde") is impeccable, alternating sequences in which she chooses to follow the characters in a calmer and more contemplative way with others infinitely more nervous and agitated, using jump cuts, ellipses and transitions indicated with fluidity by the sound. Allen's work is particularly memorable in the moment when the attack against Serpico's life is staged, when the tension is built with precision through inserts of the cop's hand struggling to break away from the door and being scratched by the wood at the same time we hear the cry of a baby and see the desperate expression of the character when he realizes the gravity of the situation.

It is also important to notice the richness of the movie in its other technical aspects, from the costumes worn by Al Pacino, which helps to establish the character efficiently, to the production design, which reflects Serpico's personality through the decoration of his apartment (and we should also notice how the huge amount of typewriters in the room next to the one occupied by the mayor's assistant helps to highlight the infernal bureaucracy that collaborates to stall the efforts of the hero). Finally, the perfect choice of locations contributes to create an urban and decadent atmosphere that is so important to the movie's success.

It is also important to notice the richness of the movie in its other technical aspects, from the costumes worn by Al Pacino, which helps to establish the character efficiently, to the production design, which reflects Serpico's personality through the decoration of his apartment (and we should also notice how the huge amount of typewriters in the room next to the one occupied by the mayor's assistant helps to highlight the infernal bureaucracy that collaborates to stall the efforts of the hero). Finally, the perfect choice of locations contributes to create an urban and decadent atmosphere that is so important to the movie's success.

In the end, however, what really matters is the emotional and psychological trajectory of the title character - and his tragedy lies not only on the impossible situation the surrounds him, but in the irreparable destruction of his dream of being an efficient cop in an incorruptible department. So, when Serpico finally lets out a small cry, we realize that, in one way or another, his battle is already lost and we're sorry not only because of his disappointment, but also because of the cynicism of the world in which he (and, even now, all of us) lives.

Pablo Villaça has been a film critic since 1994 and writes for the oldest Brazilian movie website, Cinema em Cena. He teaches a course on Film Language and Film Theory in which Sidney Lumet is a constant reference.

A writer, filmmaker and a film critic since 1994, Pablo Villaça wrote for many Brazilian movie magazines. In 2002, he became the first Latin-American critic to be part of the Online Film Critics Society, being elected its first non-English speaking Governing Committee member in 2011.