Editor's Note: This is one person's view with recommended films that represent a range of perspectives as an invitation to constructive dialogue, and we welcome respectful comments. Given the sensitivity of the issues, we will remove any comments we find inappropriate. And we invite other people who are familiar with the films that address these issues to develop their own lists for us to publish.

PART 1: INTRODUCTION AND VIEWING LIST

This series presents the situation in four installments. First, we will explore religious films. Second, we will survey attempts at good will and attempts at hostility. Third, we will explore Israel from the perspective of pro-Israeli filmmakers. Fourth, we will explore Palestine from the perspective of pro-Palestinian filmmakers.

I am selecting films that are easily available, guiding you through the multiple narratives that inform the various outlooks on this region. When students ask me whose side I am on, my answer is simple: I am on the side of the people. Palestinian. Israeli. Christian. Jewish. Muslim. Non-believer. I am not as compassionate toward the Policymakers.

A number of recent events compelled this series. Right now, we are witnessing what some call a war and others call a siege. Israeli Defense Forces and Hamas are firing on each other, again, allegedly in response to a series of killings of Israeli and Palestinian children. Though both Islam and Judaism speak of humanity as so sacred that one lost life is an incalculable tragedy, the casualties, however, are not remotely even. Palestinian deaths surpass Israeli deaths by a ratio of over 200 to 1, where 1 out of 5 deaths are believed to be children.

Related to these events, many American celebrities have disavowed their own comments, like “#FreePalestine” (by NBA star Dwight Howard and singer Rihanna), after being accused of bigotry. Meaning, in the minds of some very vocal people, “Pray for Tel Aviv” would not be bigotry, but “Pray for Gaza” (as stated and recanted by singer/actress Selena Gomez) would. All people should be prayed for, indeed, but praying for a particular group does not imply hatred for another.

Further, the Presbyterian Church voted to divest its interests in American companies involved in human rights violations, thriving on Israeli settlements in Palestinian territories. Last, President Obama just hosted his annual “White House Iftar,” commenting, among his many usual diplomatic pleasantries, that Israel has to right to defend itself. Indeed it does, but taking that point to its full conclusion, so to do Iraq and Afghanistan against us, except that when they do, we call them “insurgents”and “terrorists.”

The conversation on Palestine/Israel is, thus, one of the most impossible conversations in our society. It is difficult enough to find people who are able to engage honestly and dispassionately, and even self-critically. Some focus on human rights. Some seek a safe haven against hostilities. Some are hopeful for a returning Messiah; some seek to force his return. Some are driven by anti-Semitism, others by Islamophobia. I am not claiming to be unbiased here, but I will try to be fair.

The best way to describe my sentiments, especially regarding the future of the Palestinians and Palestine, can be summed up in one word: despair. Nevertheless, all three of the great Abrahamic traditions claim that impieties have happened here, but so too have miracles. So, we must still have hope, even if it is small.

And, with that we begin our series with Religion. Old time religion. Five movies.

The goal is to touch upon the various narratives that guide us in viewing the people, the land, and the problems. In Narrative, there are heroes and villains, and a lot of empty spaces. The Western Narrative usually leaves out the Islamic influence (especially during the Medieval period) and Colonization. The American Narrative downplays the genocide of the Native Americans and the Transatlantic Slave Trade as aberrations. Thus, narratives massage facts.

Likewise, each religion sees itself and sees others through its own lens. Judaism sees Christianity and Islam as offshoots. Christianity sees itself—rather, sees Jesus Christ—as the fulfillment of Judaism, while seeing Islam as a parallel, sometimes competing, tradition with similar origins and theologies. Islam sees itself as the oldest of religions, with Judaism and Christianity as offshoots, in that Islam claims Abraham, Moses, and Jesus as prophets of Islam as Judaism claims Abraham as a patriarch of Judaism; may peace be upon them all. The point is that when we speak of narratives, legitimacy may not come from fact but from belief. We do not believe in the narratives because they are true; they are true because we believe in them. Sometimes these narratives fit well together, and sometimes they clash. When we speak of the land called Israel or Palestine, we seem to only speak of clash.

"Kingdom of Heaven" (Scott, 2005).

This film explores the role of Jerusalem in the imaginations of the Medieval people, as a place of redemption, renewal, and self-determination, hovering beneath a dark cloud of religious triumphalism. We meet a leper King Baldwin, who seeks to keep peace by keeping Jerusalem as a place for all faiths. We watch the legendary Muslim leader Salah al-Din (Saladin) maintaining the peace, but ready to storm in if necessary. There is a brief moment where Salah al-Din offers to send the ailing King his own physician. Legend tells us that the physician was one of the greatest of all Rabbis, Moses Maimonides, though some historians disagree. In any case, threatening the peace are the militant Christian group, the Knights Templar, determined by an imagined Divine Right to rule Jerusalem and the world. In the process, we meet others who give up hope for any holiness in Jerusalem. Meaning, “Kingdom of Heaven” tells us that some come to Jerusalem seeking God, while others leave Jerusalem believing that God has abandoned it.

“Crusade” etymologically comes from “being marked with the Cross.” Its meaning is, however, similar to the meaning of “jihad,” as a struggle toward some goal. When Christians use “crusade” or Muslims use “jihad,” they speak of something ambitious, noble and non-violent. We know, however, that what Pope Urban II launched in 1095 CE was definitely violent: a holy war against the infidel Muslims for control and restoration of the Holy Land. At the same time, a group of Renegades went through particular places in Europe seeking out Jews for persecution.

The whole of history, however, tells a wider story. Indeed, Jerusalem is a place run by Romans, Jews, Christians, and Muslims in various periods, and the change of authority was usually often bloody, including the destruction of the two Temples in 587 BCE and 70 CE. But, because of the lack of material benefits and natural resources, other regions witnessed far more conflict through the generations. Meaning, Jerusalem was not, contrary to popular belief, a place of perpetual war, because it was not, save for men of piety, a place of much interest or benefit. But, as a symbol of Divine promises, it was and is something other worldly.

"The Ten Commandments" (1956)

Perhaps the greatest of all Hollywood epics. I watched this film with my family year after year every Passover/Easter, though as a child I knew more about colorful bunnies and eggs than about Pesach or Good Friday. This film gives us the story of Moses and the Children of Israel, which plays a major role in all three of the Abrahamic Traditions, though it is most central in the Jewish narrative. Moses grows up with the Pharaoh in Egypt before the Divine calls upon him. He demands the Pharaoh to turn to God, and free the enslaved Hebrews. He leads his people toward the promised land, beyond the split sea, beyond their worship of the golden calf, beyond their ungrateful demands.

In this context, we are watching this film to understand that in the Jewish narrative, Israel is three. Israel is a title given to Jacob, son of Isaac, son of Abraham. Israel is also the Jewish people. And, Israel is the land. In the Jewish narrative, the three are inseparable.

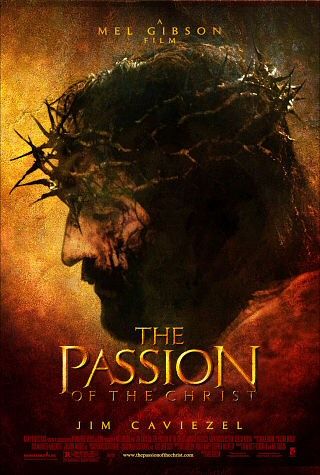

"The Passion of the Christ" (2004)

Perhaps the most powerful of all such movies, if at least because of the brutal violence inflicted upon Jesus, especially when juxtaposed with his gentle demeanor speaking to his mother, and teaching his disciples. In this film, Jesus gets betrayed by Judas; made subject to trial, crucifixion, and resurrected. The Sanhedrin regard him as a heretic for claiming to be the Son of God, the Messiah, and the King of the Jews. The Roman governor Pontius Pilate washes his hands of Jesus, literally, allowing him to get chastised, flogged, and pummeled.

In our context, this film carries multiple purposes. First, it presents the central role that Jerusalem has in the Christian narrative. Second, the film was protested for presenting a particular read of the Jesus narrative, placing most blame on Caiaphas, the Jewish High Priest, rather than Pilate, who seems comparatively humane. That narrative was repudiated by Pope Paul VI during the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s. Mel Gibson’s gifts as a director get unfortunately overshadowed by other matters in his conduct including his bouts of anti-Semitism. Nevertheless, this film is for many Catholics a sacred experience, focused on the suffering Christ, regardless of who is responsible for his death.

It is also worth noting that today, the keys to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, commemorating the site of Jesus' crucifixion and burial, have been cared for over generations by a family of Palestinian Muslims.

"The Jesus Film" (Sykes, Krish, Heyman, 1979)

The actual title of this film is simply “Jesus.” Two films about Jesus are important here because we speak of two populations of Christians. If “The Passion of the Christ” presents a very visceral Catholic experience, then this film presents an Evangelical Protestant narrative focused on the ministry and atonement.

The distributors claim that this film has a thousand translations, more than a billion viewings, and 200 million conversions. In the contemporary world, we find the Right Wing among the Evangelical Protestants as politically active and interested in the workings of the Israeli state as almost any other group. They are so active and aggressive, as a Christian Zionist movement, that we might assume they speak for all Christianity, and overlook the population of Moderate and Left Wing Evangelicals. What is their goal? Apocalypse: the return of their Lord and Savior. Narratives feature heroes and villains; such people are constantly on the lookout for the Anti-Christ.

"Muhammad: Legacy of a Prophet" (Schwarz and al-Qattan 2002).

The most viewed film about the life of the prophet Muhammad is Moustapha Akkad’s “The Message” (1976), featuring Anthony Quinn and Irene Papas. But, that film does not engage the political treachery Muhammad faced by three of the Jewish tribes in Arabia, and it does not explore the Night Journey, during which Muhammad visited Jerusalem on his way to passing through Hell and Heaven before a special meeting with the Divine, in a path later lifted by Dante. This documentary about Muslims in America, interspersed with explorations of major moments in Muhammad’s life, studies all those events directly.

Within Jerusalem, the al-Aqsa campus is for Muslims the third most sacred site on the planet, after Mecca and Medina. Near its center, the golden domed, blue Dome of the Rock, marks the spot where Muhammad ascended. That whole structure happens to sit on top of the site of the previous Temple, Judaism’s most sacred center, where Jews today visit, expressing prayers at its Western Wall.

Jerusalem is, thus, central to all three of these traditions. More importantly, the American narrative about Jerusalem is that the conflict is driven through religion, from start to finish. That is only a partial truth, as we will see in subsequent entries.

Next: Attempts at Good Will and Attempts at Hostility.

Read the other three parts of Muzaffer's series here, here, and here.Omer M. Mozaffar teaches at Loyola University Chicago, where he is the Muslim Chaplain, teaching courses in Theology and Literature. He has given thousands of talks on Islam since 9/11. He is also a Hollywood Technical Consultant for productions on matters related to Islam, Arabs, South Asians.