On a day when the sun is finally shining and it doesn’t even look like rain, Cannes doesn’t automatically inspire dark thoughts of criminal masterminds and evil-doers prowling the streets and owning the night. But, just as film people from every nation on earth are gathered here for two weeks, so are the pickpockets, the cat burglars, the jewel thieves and the con artists, beggars, and grifters of every stripe.

Just yesterday, the trade papers carried the story that more than a million dollars in Chopard jewels that had been brought to Cannes to loan to stars for their gala appearances had been stolen from a hotel safe. This is only the big stuff. Every year, those of us who come here regularly trade our latest stories of purse-snatchings, holdups, child pickpockets, and those brazen nocturnal thieves who climb neon signs, awnings, and gutter-pipes to reach open hotel windows to snatch any valuables left within reach. It once happened to me, so I know, and never slept with an open window again.

Evil ran rampant in the Grand Théâtre Lumière this morning, with the Dutch competition entry “Borgman” by Alex van Warmerdam (“The Last Days of Emma Blank”), but the over-arching scheme of the director’s dark intentions never became fully clear. Appearing to be very much influenced by the themes of Michael Haneke films including “Funny Games” and “The White Ribbon,” “Borgman” features an exceedingly privileged upper-middle-class family bedeviled by the arrival of a sinister figure and his henchman, who infiltrate and destroy their way of life.

In the film’s opening sequence, a priest celebrates mass, then grabs a shotgun and joins assistants with sharpened spears to hunt several bedraggled men living in leaf-covered hidey-holes in the forest. The men escape, and their leader Borgman seeks the use of a bathroom by ringing doorbells at secluded homes. At one, the husband ferociously assaults him but the wife later takes pity on the injured man, giving him a bath, food and a place to sleep in the garden shed while her husband is at work.

So far, audience sympathy is with this battered loner, and the natural assumption is that he represents some ethnic or political minority being hunted for extermination by authority figures. The assumption is gradually dispelled as Borgman gains a strange power over all but the husband. He does away with the family gardener and succeeds in replacing him. The wife — who is troubled by violent nightmares which include erotic images of Borgman — the au pair girl, and the three children come under his spell. The husband develops an odd X-mark on his shoulder.

Sinister clues are dropped everywhere, but it’s never clear to what end. When Borgman’s cohorts, who are busy perpetrating murders elsewhere, phone him for instructions, he often ends the conversations with “It’s not time yet.” A pair of emaciated long-snouted hounds appears out of nowhere to roam the house one night, sniffing the young nanny as she sleeps, then disappear. Borgman whisks the kids off to visit an underground bunker and gives them some kind of Kool-Aid to drink.

Portentously, the wife says, “We are the fortunate, and the fortunate must be punished.” The implications are satanic, and a global takeover, one family at a time, is hinted at, but the accumulation of hints and sinister happenings never comes together into something larger. Call it Haneke-lite or Haneke-wannabe, but it’s an odd choice for the competition, except for a possible political need to represent a diversity of European nations.

The dark side was manifesting itself today, and final solutions became the theme for the rest of the day. Two films, “The Missing Picture,” a French/Cambodian co-production, and “Death March” a Filipino film, both premiering in Un Certain Regard, addressed the subject of real-life evil in stylistically extraordinary ways. The horrific reign of Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge is the subject of Rithy Panh’s personal essay documentary “The Missing Picture.” Panh, much of whose earlier work is in the human rights vein, previously distinguished himself with “S21, The Khmer Rouge Death Machine.”

The first shot of “The Missing Picture” depicts a great pile of 35mm film heaped on a concrete floor. The deteriorating footage is symbolic of the lost, fragmented or hidden images of actions that willfully destroyed a nation. The filmmaker seeks specific evidence of mass murder.

Utilizing small, painted clay figures, the film presents the home village of Panh’s childhood before the Khmer Rouge came to power. The dollhouse-sized markets, schools, and rice paddies soon give away to other scenes of black-clad clay prisoners in the work camp where, as Panh narrates, he was taken with his family at the age of thirteen.

To his own powerful memory-driven narration, Panh alternates increasingly elaborate scenes of his clay figures in the camp environment with sequences of archival footage or those in which his cartoon-like figures are juxtaposed against filmic backgrounds. Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t.

The figures are static, and as intricately formed as they are and as elaborately staged, they don’t move, so their scenes are static. The juxtaposition is most effective when they have something to do: In the foreground of the frame, a little clay cameraman aims his camera at the dictator Pol Pot, seen in archival Khmer Rouge footage in the background, and the film’s merging of memory and historical record comes to life.

As I left “The Missing Picture,” I was startled at the sound of blood-curdling screams on the Croisette. Then I realized that it was only the costumed stooges of Troma holding a fake street demonstration to once again promote “Return to Nuke ‘Em High” or some other exploitation masterpiece.

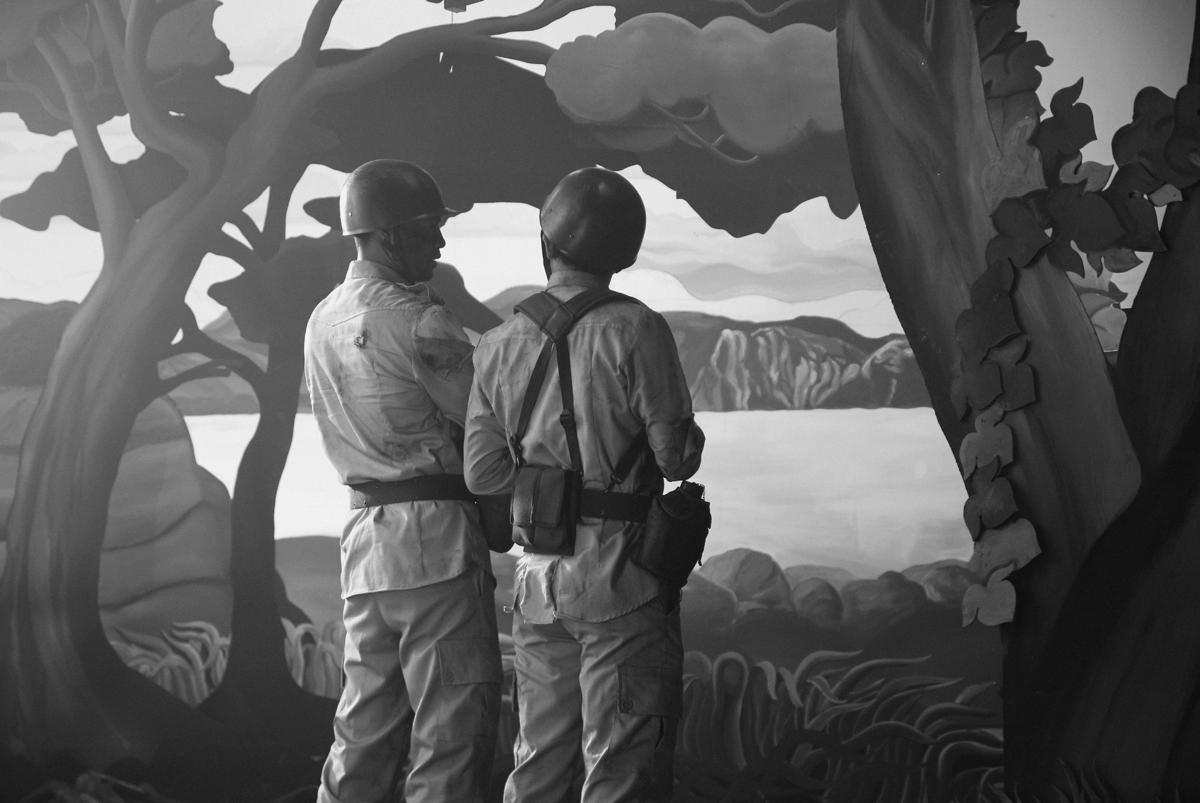

Screams were an apt lead-in to “Death March” by Adolfo Borinaga Alix, Jr., a film that evokes the Bataan Death March in a surreal, stylized drama set entirely in a studio against painted backdrops, cardboard trees, and a sea fashioned from plastic bubble-wrap. Shot in black-and-white with Filipino, American, and Japanese actors and much fog and smoke, the film is an eerie meditation on the psychology of men facing incomprehensible brutality.

“Death March” is conceived as a group experience, but filmmaker Alix zeroes in on several soldiers who periodically come to the fore, including a Filipino who hallucinates dead companions, an American trying to nurse his dying captain, and a compassionate Japanese guard who imagines himself hovering above the men as a glowing angel with enormous white-feathered wings. Swift and exceptionally cruel executions single out others for brief recognition as individuals.

Alix’s method is surprisingly effective, although this isn’t a film for everyone. It is best appreciated almost as a dance of seething, scrambling, stumbling bodies, to the cacophonous chorus of groans, pleas, and exploding shells. Periodically, faces and eyes are fixed in sudden still moments that underline the horror and chaos.

Eighty-seven-year-old director Claude Lanzmann of “Shoah” fame was welcomed to the stage of the Salle Debussy tonight by Cannes artistic director Thierry Frémaux, to a standing ovation. Lanzmann profusely thanked his crew and all who helped make his new film “The Last of the Unjust” possible, and the two joked about previous discussions regarding whether the film was to be presented in or out of competition, before the genial director planted a huge kiss on Frémaux’s cheek.

Lanzmann’s place in film history is assured by his landmark “Shoah,” and “The Last of the Unjust” grew out of the hours of unused interview footage that he shot of Benjamin Murmelstein, the last president of the Jewish Council of Elders in the Theresienstadt ghetto in what was then Czechoslovakia. In the lengthy rolling text that begins the film, Lanzmann makes it clear that his film will exonerate Murmelstein, who has long been a controversial figure whom some had accused of collaboration with the Nazis.

In characteristic fashion, Lanzmann is meticulous and thorough in establishing the time, the places, and the progression of events in Murmelstein’s seven-year relationship, from 1938 to 1944, with Adolf Eichmann, who in every way his overlord and the arbiter of the fate of the community that the Jewish Council administered. The film intercuts lengthy sequences of the interviews with Murmelstein, which were conducted in Rome in 1975, with Lanzmann’s present day visits to relevant locations in Vienna and the Czech Republic.

Although at Eichmann’s war crimes trial it was claimed that his participation in Kristallnacht could not be established, Murmelstein provides his direct eye-witness account of Eichmann personally smashing sacred objects with a crowbar as he directed SS men in the ravaging of a Vienna synagogue. Murmelstein refutes Hannah Arendt’s famous statement about the banality of evil, saying in reference to the trial, “The corrupt Eichmann was never shown.”

I felt no aura of the day’s specters of evil in the streets of Cannes as I walked back to my hotel. A new bistro has opened along the narrow pedestrian passageway I take up to the rue d’Antibes from the Palais, and revelers with drinks in their hands were mixing with the people who just gotten ice cream from the gelato shop a few steps away. A rock band was playing on a temporary stage in front of the nearby church, Notre Dame de Bon Voyage. It’s Sunday night and it’s not raining.