Editor’s Note: On the day Roger passed away, his longtime friend and Sun-Times colleague Robert Feder wrote the following essay.

On the night Gene

Siskel died, Roger Ebert and I spent an hour on the phone together,

talking about the loss of our dear friend and lamenting that we never

knew how gravely ill he was.

There was no

question that Roger respected Gene’s decision to keep the extent of his

illness private. But it saddened Roger that he was never able to reach

out to Gene in a meaningful way at the end. Just weeks earlier, Gene had

told us he was taking an indefinite leave of absence, but was in a

hurry to get well “because I don’t want Roger to get more screen time

than I.” We both believed he’d be back.

I’ll

never know for sure, but I always suspected that Roger’s experience with

Gene had a lot to do with how open and forthright he chose to be about

his own health problems in the years that followed. He shared

everything. Even when some of those closest to him discouraged him from

showing his disfigured face in public, Roger set vanity aside and moved

forward with courage and grace that inspired us all.

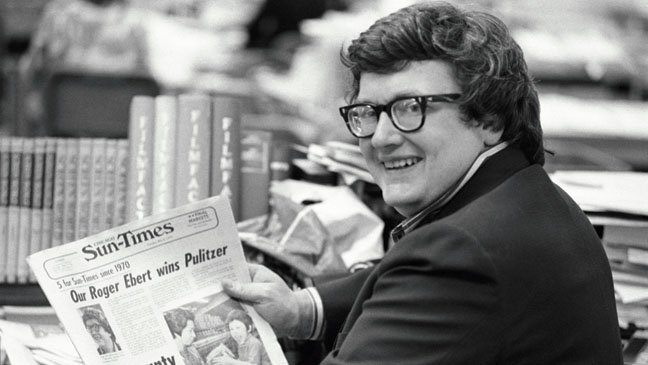

I

was almost a generation younger than Roger and didn’t get to know him

personally until I joined the Sun-Times in 1980. By then, he’d already

won the Pulitzer Prize, become a rising star on public television, and

left his legendary drinking and carousing days behind. But he was still

very much an endearing and approachable presence in the newsroom — even

to a rookie reporter toiling as a legman to the paper’s TV critic. His

nickname for me was “Scoop,” and he’d often tease me about “putting

little pills” in Gary Deeb’s coffee as if I were plotting against my

boss.

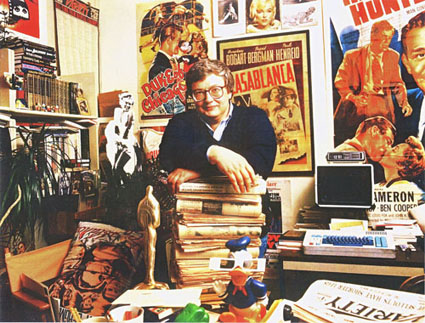

For many years, my desk was right outside

Roger’s door, and I’d find any excuse to peek inside. His office was

more like a museum, filled from floor to ceiling with movie posters,

books, toys, treasures and tchotchkes of all kinds. As cluttered as it

was, he knew precisely where everything belonged, right down to the last

Mickey Mouse figurine.

When Roger held court

in the middle of the features department, all other work stopped. He’d

start out talking to one or two friends and soon an impromptu audience

would assemble to hear him tell stories, share the latest joke he’d

heard (he always laughed the loudest at his own punch lines), or deliver

a wicked impersonation of Irv Kupcinet.

Not

that it was all fun and games. When Roger got down to business, no one

could match his performance as a writer. Everything he created sparkled

with his unmatched wit, intelligence and humanity. And he was a dynamo

on deadline.

Whenever I told someone I worked

for the Sun-Times, invariably the first question that followed was

whether I knew Roger Ebert. He personified the paper and was its heart

and soul. For at least the last quarter-century, no one came close to

his stature as its biggest draw and brightest star. First and foremost

he thought of himself as a newspaperman — specifically a Chicago

newspaperman.

As busy as he was, Roger was

unfailingly thoughtful and generous. Countless times he’d send me notes

of praise or share invaluable news tips. More than once, when he felt I

had been unfairly attacked for something I’d written, he publicly rose

to my defense. In more recent years, a tweet from Roger to his 841,481

followers with a reference to my blog would send my page views

skyrocketing. He never asked for anything in return.

I

danced at his wedding to Chaz at the Drake Hotel, I celebrated at his

annual Fourth of July parties in Michigan, and I cheered with all my

heart at every honor and accolade bestowed on him.

Best of all, I rarely missed a chance to tell him how much I cherished his friendship.