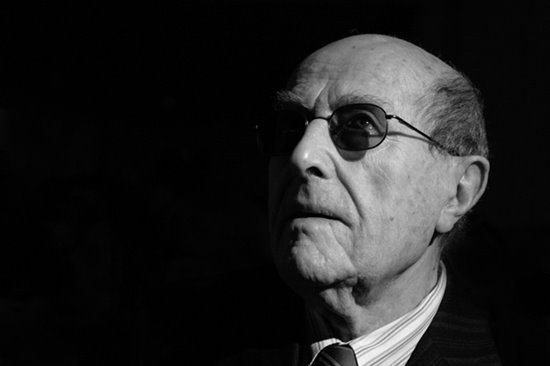

The Portuguese master Manoel de Oliveira appeared one of those extraordinary figures who’d be forever among us, ruminating in his mesmerizing hybrid style that encompassed art, photography, literature, painting and music.

A major figure in international cinema, Oliveira died Thursday, April 2nd, at the age of 106, in his hometown of Porto. Put in perspective he was born more than five years before the start of the First World War. He was a contemporary of Robert Bresson, Yasujiro Ozu and Samuel Fuller. His life and career are virtually synonymous with the history of narrative cinema. He is the only director whose career spanned the silent era to the birth of European modernism and ended in the digital age.

He made more than 60 films ranging in length from several minutes to seven hours (his extraordinary “The Satin Slipper,” his 1985 adaptation of the Paul Claudel play). Yet there is also a painful sadness and anger about his life because of the nearly three decades (1942 to 1971) interrupting his first and second features, the primary cause of his artistic inactivity being his political and moral opposition to the Salazar regime.

Until 1990, Oliveira’s work was only available at museums and film festivals. The critics Dave Kehr, Jonathan Rosenbaum and the academic and festival programmer Richard Pena were his early American champions who helped make the case for his greatness. “How can I persuade you that the best new movie I’ve seen this year, the only one conceivably tinged with greatness, is a voluptuous four-and-a-half hour Portuguese costume melodrama?” Rosenbaum began his seminal 1981 review of Oliveira’s fantastic “Doomed Love.”

The turning point for many was the 1990 Toronto Film festival, which put together an exhaustive and nearly complete retrospective of his work. What had been for many so elusive and fragmentary was now clearly in our grasp. I remember seeing about seven or eight of the films at Toronto that year, and I was hooked.

He was too fiercely uncompromising and his work to allusive, poetic and idiosyncratic to ever achieve wide success. Even otherwise sympathetic festival crowds showed the occasional impatience. In Toronto in 1992, Oliveira showed “The Day of Despair,” not a major film by any means though because it was about the life of the writer Camilo Castelo Branco, a key figure in his art, it was an important one.

As I recall the movie was fairly severe and though it ran less than 80 minutes, it opens with a seven-minute take of Oliveira’s camera fixed on the wheel of a horse drawn carriage. As the duration of the shot played out, you could feel the air in the room seep out. He pushed his art, and it helped distill a baroque sensibility that was alternately playful, emphatic, percussive and open.

He lacked a single title to identify his style, themes and major concerns, which is to everybody’s advantage, I think, because it forces you to seek out as many films of his as possible. I was drawn early to how he used space in his movies, and how stylized and avant-garde he was in conception; the use of sets for instance in his great 1990 “No, or the Vainglory of Command,” about Portugal’s reckless military adventurism and disastrous colonial actions.

The body of work is something to behold. Oliveira negotiates mysterious, private worlds of grief, loss, beauty and death. They probe or dig into the emotional currents of their characters, creating lilting, poetic reveries on youth and beauty, thwarted desire and class stratification. Oliveira asked, or depending on the point of view, demanded one surrender to the mysteries, pleasures and inspiration of his work.

For me, I was drawn to a specific theme in his work that animated many of his greatest films, like “Doomed Love,” “Francesca” and “Valley of Abraham.” His movies were philosophical investigations into the nature of man, turning on good and evil.

I had the great privilege to interview him three times, once each in Toronto, Cannes and Chicago. In February 1996, I published an interview with him in the Chicago Tribune upon the release of “The Convent,” his first film with an international cast (including Catherine Deneuve and John Malkovich).

“I use landscapes very differently with each film,” he told me. “Here the landscape imitates physical images that are part of the spiritual, emotional and physical lives of the characters. The landscape reveals the conflict in the people’s lives, even in life itself. Landscape is a reality, it’s what is under our feet.“

He was 84 years old the first time I met him, and the first thing that struck me was how vital he was. Doing research on him, I was not at all surprised to discover he was a gifted and talented athlete as a young man who was a swimmer, pole vaulter, runner and also he raced sports cars. His movies evinced the consciousness of a man very much engaged with the world, or examining human behavior. Even as the late works, like “Word and Utopia,” meditated on history and mortality, Oliveira was never passive.

I have never seen his first film, the 1929 silent, “Douro, River Work,” but I have seen his first feature, the 1942 “Aniki-Bobo,” a vivid and evocative portrait of children desperate to survive on the streets. Often talked about as a neo-realist precursor, the cutting, rhythm and camera angles suggest a fully formed and striking young talent.

Astoundingly from the late 1980s to 2012, Oliveira averaged almost a movie a year. Out of this period, I would particularly recommend: “Voyage to the Beginning of the World,” an autobiographical reverie with a great, final Marcello Mastroianni performance, “Inquietude,” “The Letter,” “I'm Going Home,” the unclassifiable “Porto of My Childhood,” “The Uncertainty Principle,” “The Strange Case of Angelica,” and “Belle Toujours,” his riff on Luis Bunuel’s “Belle de jour.”

I asked him about his reputation for making his audience work. He laughed. “My films have a direct and strong relation to time and space. Each has their own rhythm, time and speed. I don’t want to cut up my shots just to satisfy the audience.

“I love my films too much.”

There is actually one film by Manoel de Oliveira I’ve never wanted to see. It’s his most mysterious project. Called “Memories and Confessions,” he made the movie in 1982 and has reportedly filled it with many autobiographical touches. He has always insisted the movie could only be shown upon his death.

That moment many cinephiles have dreaded is sadly here. Fortunately the films very much endure. Finding them requires some effort. Do yourself a favor and check them out. Prepare to be wowed by their beauty, wonder and verve.