Begin with a truck parked on a Stockholm street, the back of it piled with eerily spotless pig carcasses. From the left a middle-aged woman walks on the sidewalk, passing behind the slaughter without a glance. She has on a white coat and carries a string shopping bag and a pail. She walks swiftly into a building. There is a dissolve to an overturned stool, a slow pan across the modest apartment, and then we see the shadow of a woman’s legs and feet, dangling in mid-air. This is, as the audience already knows, the scene of a suicide by hanging.

In comes the woman, casually slamming the door behind her, taking a sharp left down the hallway. The camera moves back across the sitting room as we hear footsteps echo behind the wall, and realize that white coat is worn not by a coroner or a nurse, but a maid. The camera continues to a door that opens on the kitchen. Through that door, the camera watches the woman hang up her coat, pull on a smock, and at last enter the death room. But this maid is focusing intently on fastening her buttons, and she never looks up as she passes the dead girl’s legs. The maid opens the window, the sun flashes off the glass for a second, she glances down at the street and — finally — turns around, covers her face, and screams.

This virtuoso sequence, executed in two long takes, occurs about seven minutes into “Girl With Hyacinths” (1950), the first film I ever saw that was written, produced and directed by Hasse Ekman. Together the two shots last about a minute and a half. Which means that it took me about eight and a half minutes to go from “Hey, this is a good movie” to “Where has this director been all my life?”

There’s an answer to the second question, coming shortly. But thanks to the Museum of Modern Art, adjunct curator (and good friend) Dave Kehr, and with the programming assistance of Swedish film scholar Fredrik Gustafsson, 10 films by Hasse Ekman will be screening in New York from Sept. 9 to Sept. 18. I was able to see four; of those, three are brilliant, one very good. This series should make the case for Ekman as a true auteur: screenwriter, actor, producer and director.

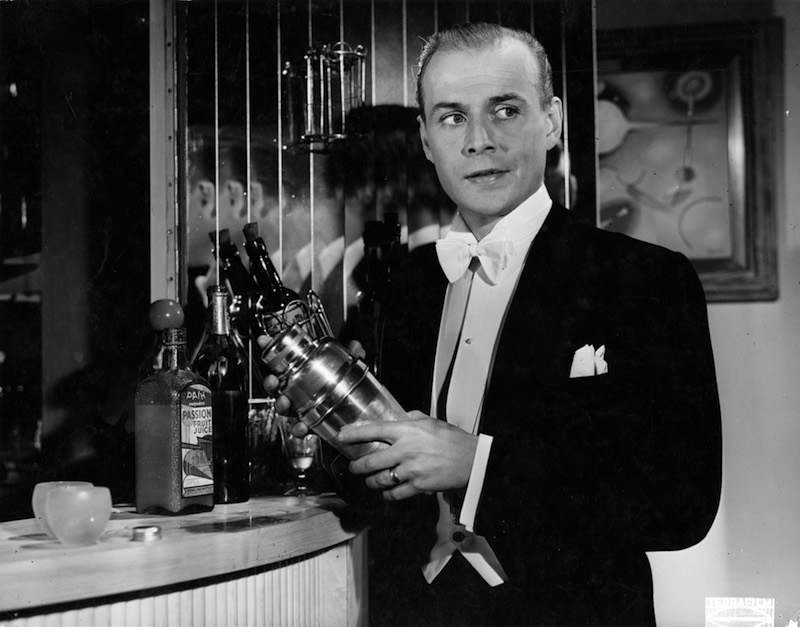

Hasse Ekman, born in 1915, was in many respects a fortunate man. As the son of the celebrated Swedish actor Gosta Ekman, Hasse had a ready-made entry point into theatre and film. At age 21 he played Gosta’s on-screen son in the Swedish version of “Intermezzo” (1936).

Yet Ekman had one disadvantage, which became significant as time passed: His best working years coincided with the rise of Ingmar Bergman, the most celebrated Swedish director of them all. For all that he was fated to be, as MoMA’s series title would have it, “The Other Swede in the Room,” Ekman always said he admired Bergman, and he acted in three early Bergman films (“Prison,” “Sawdust and Tinsel,” and “Thirst”). But after his greatest period as a filmmaker, from about 1942 to 1954, Ekman’s career began to fade. He directed his last film in 1965, almost 40 years before his death in 2004. Aside from “Girl With Hyacinths” (which was called “an absolute masterpiece” by, you guessed it, Ingmar Bergman) Ekman’s films are little known outside his own country.

“Girl With Hyacinths,” opens the series on Sept. 9, and will be introduced by Gustafsson, Ekman’s widow Viveka, and his daughter Fam. It borrows narrative techniques from “Citizen Kane” (Ekman greatly admired Orson Welles) for a quite different story. The first shots are jagged and fragmented, dialogue heard from out of frame. Like “Kane,” only in the end will the audience understand what they’ve been watching. After the suicide of beautiful Dagmar Brink (Eva Henning, who was married to Ekman at the time), her neighbor, a writer played by Ulf Palme, determines to solve the mystery attached to all such deaths: Why?

Fedora jammed on his bald head, the writer traces Dagmar like a macabre house detective. He unravels Dagmar’s lonely existence in interlocking flashbacks: her illegitimate birth, her failed first marriage, her affair with a talented but incurably alcoholic painter (a superb Anders Ek). And, above all, he tries to find the love of Dagmar’s life, the mysterious and unattainable Alex. Ekman’s plots are as fine-tuned as a Steinway, and he loves twist endings. The fadeout of “Girl With Hyacinths” is a jolter, yet perfectly in keeping with the rest of the movie, and I wouldn’t spoil it for the world.

Henning does exquisite work as Dagmar; Ekman’s collaboration with his wife seems to have been especially fruitful. In “Banquet” (1948), Eva Henning has the key role of Vica, a rich man’s daughter chained to a gleefully sadistic fortune-hunter in one of the most god-awful marriages in cinema. Henning is equally believable in her hatred of her spouse, and in her masochistic inability to break free. The husband is played, with icy cool, by Ekman himself. The plot of “Banquet” centers on the birthday bash being thrown for Vica’s banker father. The father is a decent sort, but his late life finds him with a frivolous wife; a younger son who’s a Communist and wants nothing to do with the family bank; and an effete, layabout older son who, when he’s caught pocketing some valuable bibelots, airily responds, “We live in a world of thieves. I’m just adapting.” The final banquet unfolds in masterly intercutting, as Vica’s marriage hurtles to a ghastly end. This bleakly fascinating movie, with its frank language and brutal view of sex, makes Thomas Vinterberg’s “Celebration” (1998) look like tea at the Ritz.

Ekman acknowledged that “Flames in the Dark” (1942) was partly inspired by Richard Thorpe’s “Night Must Fall” (1937), in which Robert Montgomery plays a killer living unsuspected in a quiet English village. “Flames” concerns Birger, a Latin teacher (Stig Järrel) at a boy’s school who’s virtually enslaved by devotion to his mother. But, as we soon find out, there was good reason for Mama’s concern. Once Mother dies, Birger gets hitched to another teacher (Inga Tidblad) who somehow doesn’t realize that her hubby is a psychopath. Birger’s mad compulsion is (as the title suggests) for arson. There are several hair-raising scenes of his handiwork, evoking what newsreels showed of Blitzkrieg in 1942, but it’s a comparison that Ekman lets unfold without pushing it on the audience. Ekman acts again in this movie, as a fresh-faced student whose tryst with a local waitress goes very wrong. It’s a good-looking, suspenseful effort, but a bit hampered by Stig Järrel’s soft, uncharismatic presence. A dash of Montgomery’s sex appeal would have been welcome.

The last Ekman I screened was “The Girl From the Third Row” (1949), which gives him a chance for not just one twist ending, but five, each mini-narrative nesting inside another through an astonishingly compact running time of 85 minutes. Earlier that year, Ekman had played a film director in Ingmar Bergman’s “Prison,” a film which Gustafsson says “makes the case that we are either tortured souls to be pitied or cruel animals to be loathed.” By his own account, Ekman made “Girl From the Third Row” as an explicit answer to Bergman’s movie.

Ekman plays a man of the theater, and the first scene finds him onstage in a play, declaiming about the meaninglessness of life, then shooting himself in the head. As he takes a bow to tepid applause, the camera swoops across the theater, pausing to listen in on the audience reactions. They range from hating it, to really, really hating it. After the place empties, Ekman discovers that the girl of the title (Eva Henning, who gets to be charming in this one) is hanging around backstage. She insists on telling him the story of a pretty, but fake ring, and how it passed from one hand to another. The stories are by no means all sweetness and light — some veer close to tragedy — but they all show humans are as capable of kindness and charity as they are of cruelty and selfishness. If anything, this exquisite film resembles a very Swedish version of “It’s a Wonderful Life,” with the message being simply, “We are doing our best.”

Fredrik Gustafsson, the film scholar who helped select the Ekman films for the series, has written brief explanations for his choices at his blog. He wrote his Ph.D. thesis on Ekman, determined to show the director’s “style, the ear for dialogue, the love of the theatre, the view of life as a tragic comedy and the ability to draw out the best of his fellow actors.” This MoMA series offers a rare chance for those in the New York area to see if they agree. As for me, I’m sold already.